Tiles and Ceramics of Iznik (Ancient Nicea)

Introduction with Video

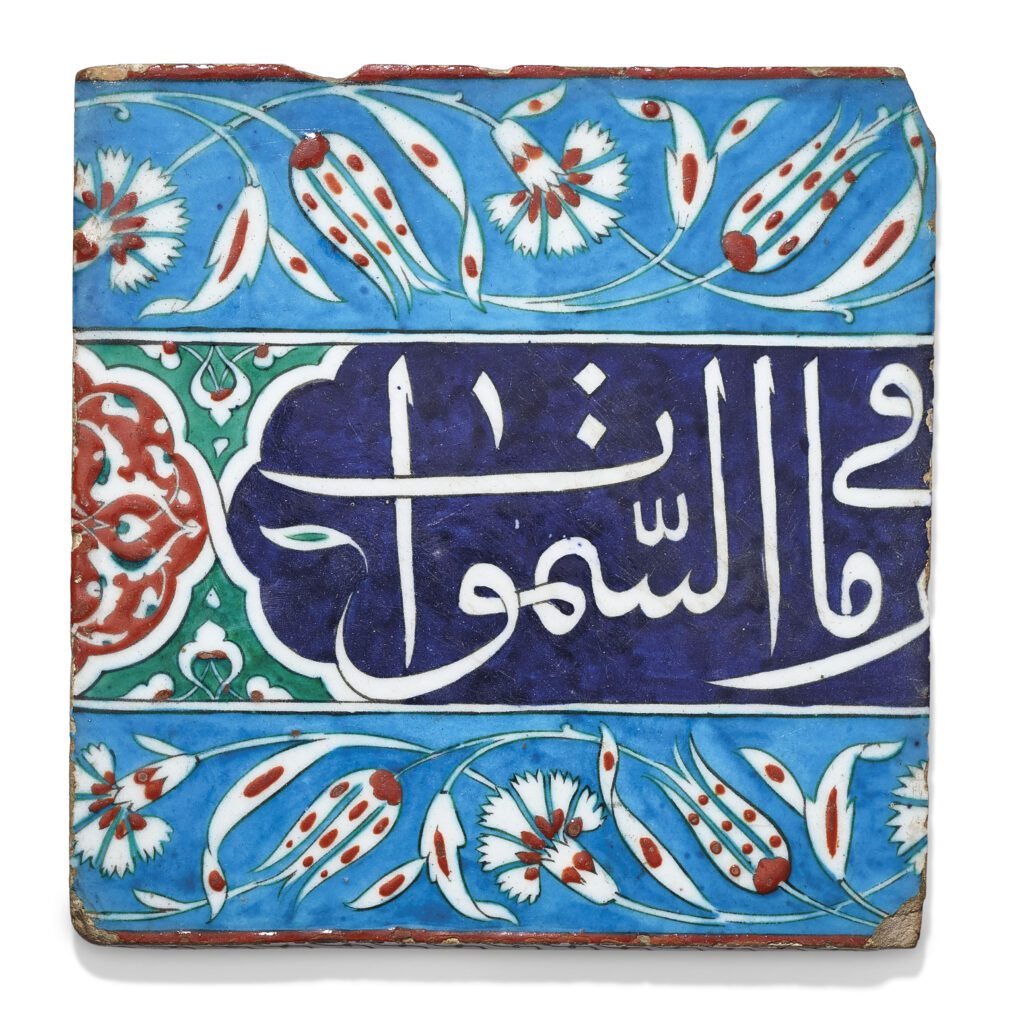

Iznik tiles represent one of the many apogees of artistic achievement in Turkish history. Without the lustrous effect they lend to some of the country’s most famous structures, much of the soul that draws people to them would evaporate. If the foundations of famed architect Mimar Sinan’s achievements are these buildings’ skeletons, then Iznik tiles are their lithe skin, their gracile eyelashes, their elegant posture. The tiles of Iznik can be found decorating monuments and religious structures; not only in Turkey, but in Cairo, Damascus, Jerusalem, and many other cities, and are proudly displayed in museums and private collections worldwide. They have inspired countless people throughout the centuries, including a new generation of artists.

What we do know is that the end of the fifteenth century heralded a new age of Ottoman ceramic art. Sultan Mehmed II held the arts in high regard, increasing court patronage in many artistic fields and galvanizing innovation in different mediums. He did so by establishing strong ties between the Ottoman palace design atelier, known as the nakkaşhane, and artists across varying mediums, resulting in consistencies of theme and motif in everything from embroidered fabrics to metalworks, and tile art was no exception. The artists of Iznik now had a concerted focus; they would supply the empire with decorative tiles for mosques, palace halls, monuments, and other official structures.

Golden Era of Iznik Tiles

By the time Süleyman The Magnificent began his reign in 1520, ceramic quality had greatly increased, new designs were beginning to flourish, and the tile art form was nearing its zenith. The Ottoman Empire was entering its richest period, both politically and culturally, a time during which Mimar Sinan was putting out one architectural marvel after another, ingeniously utilizing Iznik ceramics in his work. Colors such as olive green, grey, and manganese purple had been newly developed and were being skillfully applied to the increasingly exquisite tiles. Iznik ceramics are distinguished by their sharp clarity of design and radiant color. Both traits can be traced to the unique composition of materials used in their creation and the way in which they were processed. Compared to ceramic production in other parts of the Middle East, Iznik tiles were made from a quartz-based composite rather than a clay-heavy one. Shaped from this mineral mix, the body was coated in a thin slip layer to ensure a radiant white backdrop. Next, patterns provided by the imperial atelier were drawn on the tiles via perforated stencils and then painted with various colors. Finally, a glaze was applied to permanently seal in the design.

The late 15th and early 16th century marks the beginning of a new period in Ottoman tile and ceramic-making. The most important center active at this time was Iznik. Designs prepared by artists who were employed in the studios of the Ottoman court were sent to Iznik to be executed in wares ordered for use at the palace. The court’s patronage stimulated and supported the development of an artistically and technically advanced ceramic industry in Iznik.

The earliest example of the new styles that emerged in the early Ottoman period are the ‘blue-and-white’ Iznik ceramics. The techniques involved in their manufacture are quite advanced as compared with anything previously done. The pastes are quite hard, pure white, and of fine quality. In an analysis that appeared in his report of the 1981-82 excavations, Dr Ara Altun noted that these ceramics must have been fired at temperatures as high as 1,260 degrees Celsius rather than the normal 900 degrees adding that, at such temperatures, one is in the realm of light porcelain.3 The techniques and quality employed in these ceramics were to last through various changes in style until the middle of the 17th century.

During the late 15th and early 16th centuries, Iznik was producing far more in the way of blue-and-white wares than the wall tiles for which it was later to become famous. The styles, designs, decorations, and techniques of these ceramics are quite distinct from Seljuk traditions. These changes in the Iznik potters’ production habits are attributed to attempts to imitate the 15th-century Ming porcelains that were reaching the Ottoman court in various ways. The glazes are limpid and there is no crazing. The designs, which are given thin contours of slip, are executed and painted flawlessly. Shades of cobalt blue dominate but turquoise also appears here and there. The decorations include stylized foliage, arabesques, and Chinese clouds alone or in skillfully-executed compositions.

Iznik blue-and-whites can be classified in a number of subgroups on the basis of their motifs and styles. One group, with motifs consisting of stylized lobed leaves with curling tips is attributed to a ‘Baba Nakkas’, a chief designer at the Ottoman court studios in the 15th century, and is therefore known as the Baba Nakkas style .4 Cobalt blue in various tones is the principal color. Much later, small touches of turquoise also appear.

Around the middle of the 17th century, the quality of the Iznik potteries began to feel the impact of the economic distress and political upheavals from which the Ottoman Empire had begun to suffer. Colors become dull, the famous tomato red turns brown and even disappears entirely. Designs become crude and are haphazardly executed. Pastes become coarse and glazes suffer from cracking. During this period the Iznik manufactories apparently turned their attentions more and more to the demands of customers who were less finicky than the Istanbul court and its circles. There is even evidence, in the form of written complaints, that orders placed by the court in Istanbul were being delayed. By the 18th century, the ceramic industry in Iznik had died out completely and Kutahya replaced it as the leading center in western Anatolia.

After centuries of laying dormant, with much of the technical knowledge lost in oral traditions that died alongside their masters, the art of Iznik ceramics is beginning to revive and reassert itself. But this is an endeavor that requires more than simple replication.

Best places to see Iznik ceramics in Istanbul

- The Sadberk Hanım Museum in Istanbul houses a wonderful example of work from this period in the form of a bottle from the mid-sixteenth century. Featuring impeccable craftsmanship, deep blue and light green-grey hues, and impressively intricate borders, its presentation is breathtaking.

- Hosting the Ottoman imperial family for over 400 years, Topkapi Palace is one of the most visited museums in Istanbul. An unchanging design element of the palace throughout the years, Iznik tile panels featuring elegant flower forms adorn the walls of the Imperial Council, the Chamber of Petitions, and the Black Eunuch Court.

- Thought to be a reinterpretation of early examples of six-minareted Ottoman mosques, Piyale Paşa Mosque stands out from Mimar Sinan’s trademark style with its six-domed structure. Cobalt-blue Iznik tiles cover three walls of the interior. Some identical Iznik tile panels, on display at Victoria and Albert Museum and the Louvre, are also believed to be from Piyale Paşa Mosque.

- Designed by the great architect Mimar Sinan, the interior of Süleymaniye Mosque shows the first use of Iznik red hue in tiles. Located on top of one of the seven hills of Istanbul in Kantarcılar district, make sure to include the mosque in your sightseeing.