Ottoman Mehter Music

Video Introduction

Ottoman mehter music, which for centuries accompanied the marching Ottoman army into battle, still echoes in that of drum and zurna – an oboe-like woodwind instrument with seven holes above and one below – which are a part of folk culture all over Turkey. Mehter music was a symbol of sovereignty and independence, and its ardent sounds instilled the soldiers with strength and courage. The rousing songs and crashing sound of the great kös drums were at the same time capable of unnerving the enemy on the brink of battle, and the mehter music composers took pains to create works that produced this effect. Turquerie, the 17th century European trend of following Turkish fashion, manifested itself in many areas of art in Europe. Turquerie had an obvious influence on music, which has been one of the most vivid forms of art since the 17th century. As Turkish fashion spread, one of the things that aroused the interest of Europeans the most was the Ottoman military band, or “Mehter.” When Western musicians heard the Mehter’s tunes, they formed a musical movement known as “Alla Turca,” which means Turkish style in Italian. Nearly 150 works of operas and ballets dealing with events concerning the Turks were written in 18th century Europe.

Etymology

The word “mehter,” or “mihter” in Persian, represents a combination of the words “akber” (greater) and “azam” (very great, exalted) in Arabic. The plural of the word is “mehteran.” The place where Mehter bands practiced was known as a “mehterhane.” In the Ottoman Empire, the word “mehter” was used for tent makers, band players and the music they performed. It entered Turkish and was used to refer to the officers who maintained the sultan’s tent and carried the banner of the sultanate.

Best of Turkey and Greece with 3-night cruise (With flight from USA – Small Group)

Discover your perfect Turkey vacation package using our convenient search and filter options, tailor-making a journey that captures Turkey’s unique beauty and rich heritage just for you.

Short History

The mehter band was established in 1299 when Osman Gazi was made bey or liege lord by the Seljuk sultan Keykubat III, who sent him a tabl (kettledrum) and finial as symbols of rank. However, with the dissolution of the Janissary Corps by Sultan Mahmud II in 1826, the mehter bands were also dispersed, and not until Ferik Ahmed Muhtar Pasa founded the Imperial Military Museum in 1908 was it decided to revive the tradition. In 1914 it was reestablished as the Mehterhane-i Hakani – Royal Mehter Band – attached to the museum. The band was again abolished in 1935 by then minister of defence Zekai Apaydin Bey, only to be reformed in 1952 as an institution of historical interest attached to Istanbul Military Museum. Today the band performs several times a week at the museum, and at certain official ceremonies, and is a reminder of former Ottoman glory.

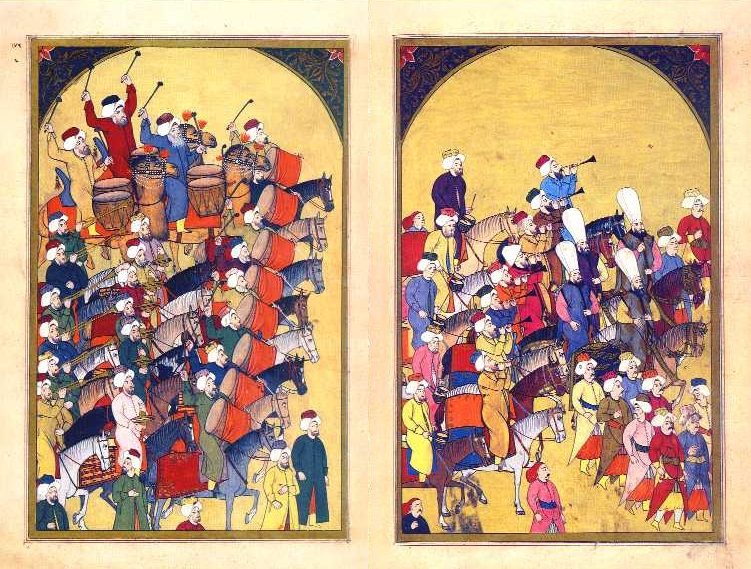

The band has its own distinctive marching step, whose rhythm is that of the words, ‘Gracious God is good. God is compassionate’. The mehter band marches behind the commander of the band or çorbacibasi, who wears a headdress known as üsküf. After him to his left and right respectively march the bearers of the white and red standards, the latter with an armed guard. Behind these march nine plume bearers three by three, the ‘plume of attack’ positioned behind the red standard. Then comes the band master in the centre, and behind him the çevgâns (jingling instruments in the form of a crescent), zurnas, trumpets, nakkares (small kettledrums beaten with the hands or two sticks), cymbals, davuls (bass drums) and finally the kös drums (giant kettledrums) played on horseback. The mehter band members form a crescent to perform, and play standing except for the nakkare players, who sit crosslegged at the righthand tip of the crescent, followed anticlockwise by the zurnas, bass drums, cymbals and trumpets. When they march, the band members pause every three steps and turn to right and left in salutation, in a rhythm set by the drums, chanting ‘Rahim Allah, Kerim Allah’ (Merciful God, Gracious God). In former centuries the mehter band used to play even at night on the battlefield to prevent the camp guards from falling asleep. As well as the instruments already mentioned, a full mehter band could also include two types of zurna (cura and kaba), kurrenay (a kind of horn with a curved end), mehter whistle, clarinet-type wind instruments, tabl, tambourine and other percussion instruments.

Janissary (Mehter) Music

The Function in Ottoman Army

The mehter bands were primarily military bands, and those under the command of generals included war drums over one metre in height known as harbî kûs or kös. These were carried on camels, and playing them with sticks demanded great skill. The 17th century writer Evliya Çelebi wrote, ‘Each kûs is the size of a bathhouse dome. They are played on feast day nights and days and their sound is like thunder.’ During performances the kös drums were placed in a line on the ground in the centre of the circle of musicians, and when marching they were loaded in pairs onto camels. The drummer rode and struck the drums to his right and left by turn. The kös was only ever played by royal mehter bands, or in that of the commander-in-chief leading the army in lieu of the sultan when on campaign. Each set of players had a leader known as aga. The leader of the bass drum players was called the basmehter aga, and the master of the entire band was called the mehterbasi aga. All the agas and the çevgân players wore white turbans wound around a kavuk (cap), a red coat over a yellow robe and red trousers, a shawl wound around the waist and yellow leather shoes. The other musicians were similarly dressed, except that their kavuks and coats were dark blue.

Forthcoming fear

The Mehter’s main task was to play in preparation for war and on the battlefield. They encouraged soldiers to be dynamic in battle, kept them awake during watch and instilled fear in their enemies. While the Ottoman army was passing near important points within its territory, the Mehter performed to announce the troops’ arrival or departure from each city, to inspire trust in the people. The march of the army during campaigns was also led by the Mehter. From the moment they entered an enemy land, the band played more intensely, and the plains and mountains resonated with the sound to fill the enemy with dread even before they encountered them. The Mehter played music many times over the course of expeditions. In order to declare the good news of the conquest of a castle or a city, the Mehter played marches as a flag was raised over the new conquest.

When castles were surrounded, attacks were carried out at certain intervals to bring down the castle. A different tune was played to ensure the regrouping of troops and another to signal breaks. All these compositions were intended to maintain the soldiers’ bodily and spiritual state of mind. The heroic melodies played while going to wars were built on the idea of instilling courage in troops and fear in the enemy during battle. The influence of the Mehter March not only on soldiers but also on beasts was also taken into consideration. Music can have both positive and negative impacts on animals during battle. The Turks realized that some melodies made animals more efficient in war. Horses would be more active when strutting to the sounds of the Mehter and, like the soldiers, they would grow emboldened, rearing up and routing the enemy. During battle, the cries of thousands of troops, horse whinnies and crashing swords cause a considerable racket. Adding to this the sound of the Mehter spread terror among enemy ranks. Western historians noted that the sound of drums, the “kös” (large kettledrum), “naqqara” (a Middle Eastern drum played in pairs) and “zurna” (shrill pipe), and the sounds of horses and soldiers caused a fright powerful enough to scare the enemy to death.

From fear to art

Ottoman armies were no longer seen as an element of fear after the thrashing they received in the second Siege of Vienna (1683). Fear was replaced by curiosity and admiration, and the Mehter was one of the sources of this admiration. When German composer Richard Wagner listened to the Mehter, he could not help but say, “that is what we call real music.” The Europeans could not forget the magnificence and grandeur of the loud tunes of the Mehter music for a long time. Until the 1700s, European military music consisted mostly of wind instruments. They began to take basic rhythms from the Mehter for their percussion instruments. It was a turning point for military music as well as for classical music. Over time, they brought changes to ensemble music, laying the foundations of the present military band. In the mid-1700s, the Mehter were loved for their clothes, instruments and music; and quasi-Mehter bands were established in European armies, especially in Prussia, Russia and Austria, some of them even playing Turkish marches.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was the composer who introduced the name “Turk” to music during the classical period from which Turquerie emerged. He was impressed when he listened to Turkish Mehter troops arriving in Vienna with Ottoman envoys. So, he wrote many piano sonatas, concertos and operas in “Alla Turca” styles. Mozart, whose art encompassed magical tales of the East, added more percussion instruments to his works under the Mehter’s influence and created a “Turkish music” according to his own understanding. In this way, he took listeners out of the air of classical Western music and dragged them into an exotic atmosphere. “Rondo-Alla Turca,” the last part of the Piano Sonata No. 11 (K. 331), which he wrote in Paris in 1778, and “Die Entführung aus dem Serail” (“The Abduction from the Seraglio”), which he wrote in 1782, are among his most famous works in this style. In addition, Turkish musical motifs are seen in his many other operas.

Johann Wolfgang Franck (1644-1710), Carlo Francesco Pollarolo (1653-1723), Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787), Johann Michael Haydn (1737-1806), Joseph Haydn (1732-1809), Niccolo Piccini (1728-1800), Carl Maria Friedrich Ernst von Weber (1786-1826), Gioacchino Rossini (1792-1868) and Franz Peter Schubert (1797-1828) are among the most famous composers who produced works in the Alla Turca style. In these compositions one can remark on the static harmonies, commutes between major and minor, rattling timbrel and thundering bass chords trying to reflect the Mehter’s percussive elements.

Fall, revival

The Mehter band, one of the most important units of the army, was an organization mainly affiliated with the Janissaries, whose power ultimately brought the state to the brink of collapse. So, in 1826, Sultan Mahmud II annihilated this elite combat regiment, throwing the baby out with the bathwater by nullifying the Mehter organization, too. In its place, a modern military marching band was formed. More than half a century later, Celal Esat Arseven, one of the major Turkish art historians of the period, reestablished the Mehterhane. The Mehter band, formed on the basis of research carried out by Ahmed Muhtar Pasha, the director of the military museum, performed its first concert since its disbandment in 1911. However, after the declaration of the Republic, the ensemble was abolished again as a reminder of the Ottoman period.

As a result of these favorable conditions formed in 1952, a Mehterhane was established within the Turkish Armed Forces (TSK). However, the lyrics of the anthems were censored. The names of the Ottoman sultans were removed and expressions reminiscent of the old era were removed. Despite this, however, it received great fascination from the public. In many cities, municipalities established their own Mehter bands. The Mehter band, which is still in place today, has toured many countries around the world and performed concerts with the Red Army Choir in Russia. At the Istanbul Military Museum, concerts are held every day, except Monday and Tuesday, including weekends, taking the audience back to a time centuries ago.