The Orsay Museum

Introduction

Le Musée d’Orsay, home of Impressionism, is a trendy destination in Paris, with 3.3 million visitors annually. It’s one of the world’s foremost museums, one of our favorites, and one you should not miss. But popularity comes with a price — long ticket lines. It is located on Paris’s Left Bank in a repurposed Belle Époque train station overlooking the Seine. It is sometimes overshadowed by the much larger and more famous Louvre Museum across the river.

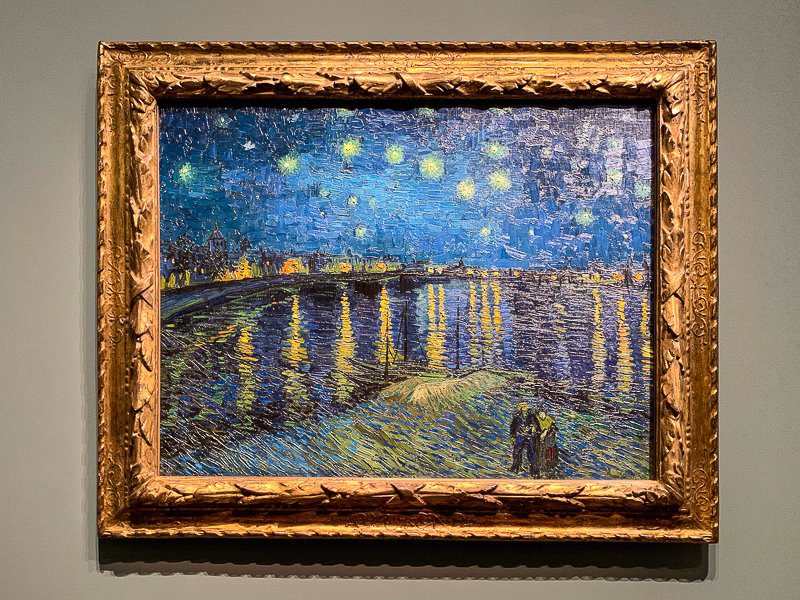

But the Orsay’s many treasures earn it a spot on your Paris “bucket list” – many visitors say it’s their favorite museum. This is where you’ll see the world’s best collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art – masterpieces by Vincent Van Gogh, Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne, Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin, Pierre-August Renoir, and other famous artists.

Plus, you’ll find much more to see and do here besides the art, including a few surprises.

Schedule

Days open: Tuesday through Sunday

Days closed: May 1, December 25, all Mondays

Hours open: 9:30 – 18:00 on Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday – Sunday; 9:30 – 21:45 on Thursday

Last admission: 45 minutes before closing

Musée d’Orsay Address & Public Transportation

Location: 1, Rue de la Légion d’Honneur, 7th arrondissement

Metro: Line 12, Solférino station

RER C: Gare du Musée d’Orsay station

Bus: Lines 21, 27, 38, 85, 96

Things to Know Before Your Visit

- The Orsay Museum is wheelchair-accessible, and loaner wheelchairs are available.

- Free priority admission for disabled visitors and accompanying persons is available upon presentation of proof of disability (usually at Entrance C, but check signs on the day of your visit).

- Due to security considerations, suitcases, backpacks, and travel bags must be smaller than 56 x 45 x 25 cm (22 x 17.8 x 9.9 inches). You may leave them in the cloakroom if space is available; otherwise, the cloakroom is restricted to objects not allowed in the museum areas.

- Once you leave the museum, you can’t re-enter with the same ticket.

- Plan to spend about 2 hours here if you want to see only the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist collections and 3-4 hours if you’ll visit the Special Exhibits and some or all of the other art. If you opt for lunch at either of the two main restaurants and do a traditional 3-course meal, count on another couple of hours for that. If you want to see the museum’s most famous pieces and learn a little about them without spending at least half a day here, consider one of the efficient 2-hour guided tours.

History

Musée d’Orsay occupies a former train station, Gare d’Orsay, built within two years for Paris’s Universal Exhibition in 1900. The station showcased the world’s first electrified city rail terminal and served as the arrival and departure point for destinations southwest of Paris – you can still see the names of these cities and towns written across the front of the building.

In addition to 16 tracks and other infrastructure related to train operations, the building also included a 370-guestroom luxury hotel at the southwestern corner of the building, which continued operating until 1973. Although the hotel no longer exists, you can (and should) visit the hotel’s grand Belle Époque restaurant, now called Le Restaurant, and see the glamorous crystal chandeliers and elaborate gilded and painted ceiling and walls. Technological advances soon resulted in longer electric trains, making the station obsolete for long-distance runs due to its too-short tracks. By 1939, it could be used only for shorter suburban trains.

At that point, the station became the proverbial “cat with nine lives” as it served as a mail depot during World War II, an exchange center for war prisoners, a film set, a city parking lot, a storage site, a temporary auction house, a vaudeville theatre, and a pop-up exhibition center. In the end, preservationists prevailed. Permission to tear down the station to build a large international hotel on the site was denied in 1971. Within a few years, plans were underway to transform the space into a museum focused on art from 1848, the cut-off for the Louvre, through 1914, where Centre Pompidou begins. The new museum opened to rave reviews on December 1, 1986, and its collections and popularity have grown ever since.

The Orsay Museum Sections

To experience the mesmerizing interplay of colors, light, and shapes on canvases by Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists, head straight to the galleries on the museum’s 5th level, where you’ll find room after room filled with stunning masterpieces.

These are the paintings that rightfully make the Orsay famous, as the crowds of fans surrounding the photos demonstrate, so for some paintings – almost anything by Van Gogh, you’ll need patience to get a good view. But the effort is worth it.

No matter how many times you may have seen photographs or prints of these paintings, the experience of viewing the originals is so much better. A camera can’t adequately capture the nuances of color, reflections of light, and the 3-dimensionality of brush strokes on canvas you’ll see in real life.

The Orsay’s lighting is superb, and the museum lets you get close to these masterpieces without risking the embarrassment of setting off the alarm system. Today, Impressionist art in no way seems radical or innovative because we’re used to it – it’s part of our cultural landscape. Even if we don’t view Renoirs or Monets daily (and how many people do?), we see their influence in colorful, light-filled images on greeting cards, advertisements, and Instagram.

But when Impressionism burst upon the Parisian cultural scene in the early 1860s after a group of young French painters, including Monet, Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frédéric Bazille, plus the somewhat older Édouard Manet, rebelled against the rigid constraints of “Academic” painting then in vogue, the establishment artists felt rocked to their core.

For over three centuries, the French Académie des Beaux-Arts defined what art should look like by blocking “deviant” artists from showing their work at the prestigious annual Salon de Paris art show, a source of coveted prizes, commissions, and publicity. The Academic style favored by the Academy favored realistic depictions of historical or mythological scenes, preferably in primarily dark colors, often topped with a yellowish-brown glaze. In contrast, Impressionist artists embraced brighter, lighter colors with spontaneous (vs controlled) brush strokes to create subjective “impressions” of landscapes and contemporary life.

Unsurprisingly, the Academy barred most of the Impressionists’ work from being shown at the 1863 Salon. However, after Napoleon III (who had seized power and appointed himself Emperor in 1851) looked at the rejected paintings, he decreed that the public should judge. Even with Napoleon III’s intervention, the first Paris exhibition of Impressionist art did not occur until 1874, when 30 artists banded together to put on their show. Most critics panned it – but the public loved it because they felt it resonated with modern life.

One reason why Impressionist art remains so popular today is its accessibility. We don’t need art history expertise to appreciate the joie de vivre in the interplay between light and colors. We can easily relate to the everyday scenes and places; stroll down almost any street in Paris, and you’ll see outdoor cafes like the ones the Impressionists painted. Stand on the banks of the Seine River on a night, and you can feel the same magic Van Gogh tried to capture as he painted the stars over the Rhône River. Make the 45-minute trip to Monet’s home in Giverny, and you’ll see the pond daylilies he featured in many of his most famous works of art.

When Impressionism peaked around the mid-1880s, artists were already pushing their boundaries as the Post-Impressionism movement emerged. Artists initially continued to focus – mostly – on real-life subjects. Still, they applied their paint thicker, chose more vibrant and less unnaturalistic colors, and played with shapes, often deliberately distorting or changing “reality” and sometimes using geometric and abstract forms. As you will see as you walk through the galleries featuring Post-Impressionist art, this was not a unified movement or a specific style. Some Post-Impressionist artists focused on blocks of color, rendering their subjects on a flat plane. Others fell under the spell of Japanese woodblock prints. Still others turned to decorative arts. An influential group of young French artists who called themselves Les Nabis turned away from painting what they saw in real life to make their art about symbols, metaphors, and meanings.

Look closely, and you can see the beginnings of Cubism, Fauvism, Expressionism, and Surrealism, as the 1890s gave way to the 20th century and ushered in what we regard as the modern art period. Want to see more art that grew from the Post-Impressionism movement? Head over to Centre Pompidou (home to the Musée National d’Art Moderne) and the Museum of Modern Art of the City of Paris at the Palais de Tokyo and immerse yourself in their extraordinary collections of contemporary and modern art.

But first, there’s a lot more to see and do at the Orsay.