Fez Travel Guide

Introduction

Unlike bustling Marrakech, Fez still retains much of the traditional culture that has defined it, making a trip here a glimpse into Morocco that was as well as insight into Morocco on the cusp of change. While much has changed in Fez over the years, from imperial capital to being one of Morocco’s most significant cities, much has stayed the same. The city remains Morocco’s spiritual heart thanks to the strong ties to religious schools and Islamic scholars. Its car-free medina has also remained a crossroads for trade and a center for teaching the traditional trade crafts of Morocco, such as intricate wood carving, zellige tilework, and hand-wrought metalsmithing. Fez attracted scholars and philosophers, mathematicians and lawyers, astronomers, and theologians in its heyday. Artisans built houses and palaces, kings endowed mosques and madrasas (religious schools), and merchants offered exotic wares from the silk roads and sub-Saharan trade routes. Although Fez lost its influence at the beginning of the 19th century, it remains a supremely self-confident city whose cultural and spiritual lineage beguiles visitors. Something of the medieval remains in the world’s largest car-free urban area: donkeys cart goods down the warren of alleyways, and while there are still ruinous pockets, government efforts to restore the city are showing results.

Fez, The Soul of Morocco

At twelve hundred years old, Fez is known by many names. The “oldest living medieval city of the world” and the “soul of Morocco” are but a couple of nom de plumes attached to this beautiful city. Join the traditionally dressed crowds of people and donkey carts as they thread their way down the Talaa Kebira, the main thoroughfare of Fez. You can feast your eyes on beautiful relics, shrouded figures, and mazelike streets. Spires of minarets rise above the centuries-old buildings, giving the city a mysterious feeling. Luckily, many structures have stood the test of time and are being restored to their former beauty. Unlike other cities in Morocco that have been torn down to make way for new, Fez has embraced its past. Some travelers have called Fez mythical because of its connections to the past. Which are real, and which are fodder of myths?

It might be said that Fez is the medieval city it once was. Compared to Marrakech, Fez is considered the cultural and spiritual center. Fez has sunk more profoundly in its roots of the Islamic past. While Marrakech and Casablanca have opened up to more Western influences, Fez has nurtured its history. It is living its history. French occupation brought a new city called Fez, which is mainly ignored. Instead, forked paths of the medina hold most of the attention. High walls carved with symbols, mosques hidden away that call to the faithful, and old ceramic workshops billowing black smoke into the ever-blue sky all seem to transport one’s senses to a long-ago time. Every day, you can see the mourners carrying candles to the tomb of Moulay Idriss II, paying homage to the city’s founder.

This old city plan is based on the rule of five from the Koran. There are five concentric rings to the medina. At the center is the holy or religious places. The next ring would be the souks and places where the residents make a living. Residential areas make up the next ring. Each neighborhood would have five obligatory institutions: a mosque, a school, a shared fountain, a shared bread oven, and a hammam. Of course, most of this part is not open to visitors. Souks and the center of the rings would be the place for visitors.

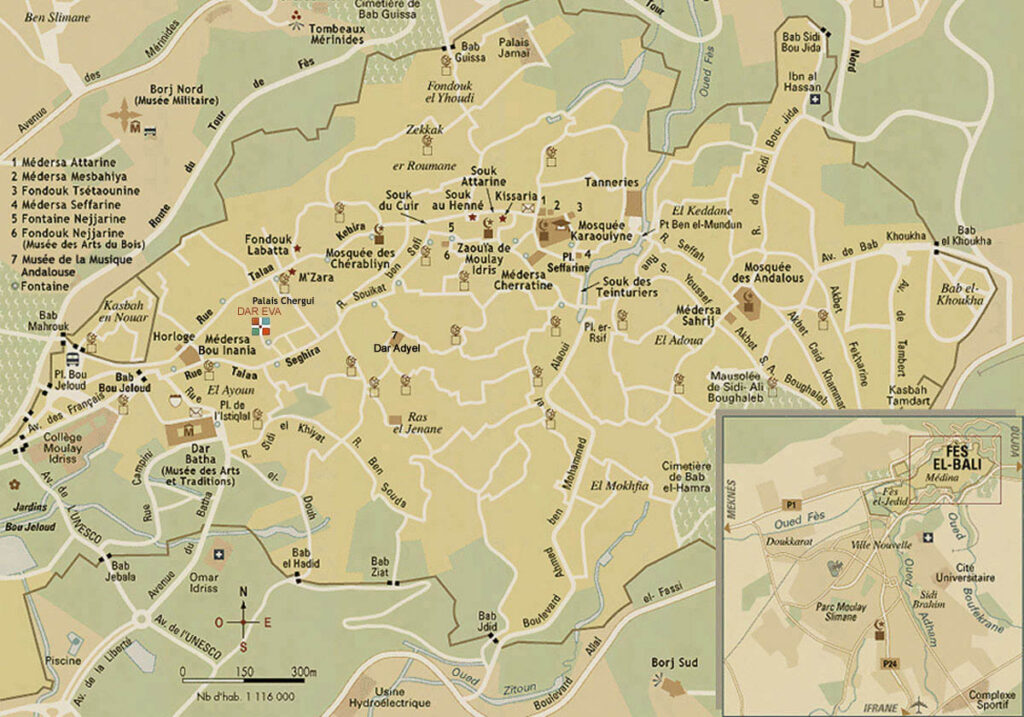

When you stroll beneath the famous blue gate of Bab Boujeloud, you are transported 1,000 years back in time. The bustling cafés and outdoor markets quickly give way to quiet, narrow streets where children are challenged at play, and donkeys are hard at work carrying supplies up and down the medieval city’s twisting, mud brick corridors. This is the oldest part of Fez, Fez el-Bali, and it is the world’s most significant car-free urban space and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This is where most travelers spend their time in Fez.

Besides the labyrinthine Fez el-Bali, there are two other parts to the city: Fez el-Jdid (the “new part of the city,” which is still a few hundred years old) and Ville Nouvelle (French for a new city, constructed under the French Protectorate era in the first half of the 20th century). Though most of the activities and sites of interest to travelers are in the old city, many travelers do find themselves venturing into Fez el-Jdid to visit the Jewish Quarter and Batha Museum and to take a stroll in the Jnane Sbil gardens. At the same time, most avoid the Ville Nouvelle altogether unless they are traveling to the airport or train station or getting a bite to eat somewhere a bit more modern than the offerings in Fez el-Bali.

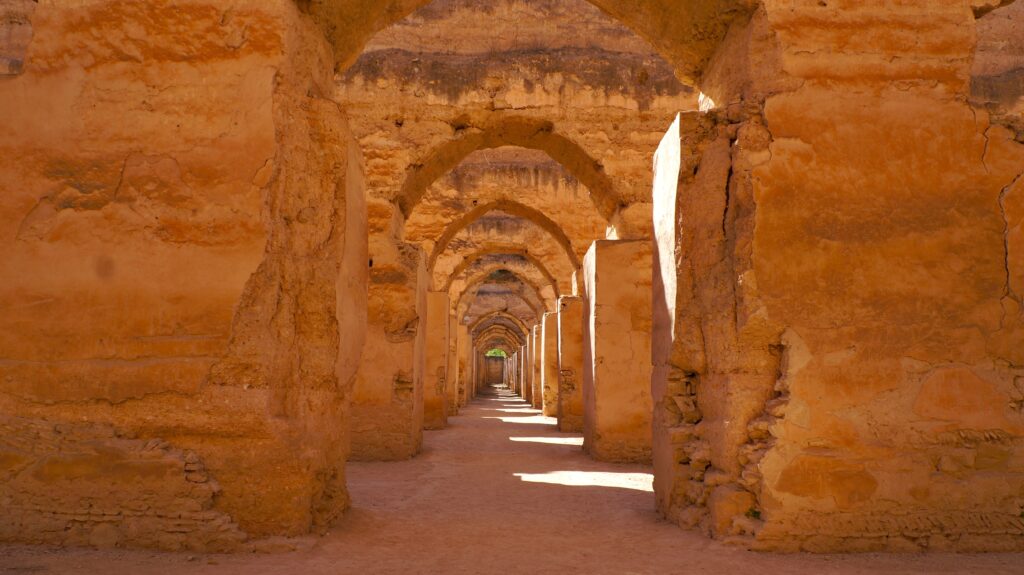

Heri el Souani

Also known as Dar el-Ma (Water Palace) for the Agdal Basin reservoir beneath, the granaries were one of Moulay Ismail’s most significant achievements and are the first place any Meknessi will take you to give you an idea of the second Alaouite sultan’s glorious vision. The Royal Granaries were designed to store grain as feed for the 10,000 horses in the royal stables—not just for a few days or weeks but over a 20-year siege if necessary. Ismail and his engineers counted on three things to keep the granaries cool enough that the grain would never rot: thick walls (12 feet), suspended gardens (a cedar forest was planted on the roof), and an underground reservoir with water ducts under the floors. The high-vaulted chamber on the far right, as you enter, has a 30-foot well in its center and a towpath around it—donkeys circulated constantly, activating the waterwheel in the well, which forced water through the ducts and maintained a stable temperature in the granaries. Behind the granaries are the remains of the royal stables, roofless after the 1755 Lisbon earthquake. Some 1,200 purebreds, just one-tenth of Moulay Ismail’s cavalry, were kept here. Stand just to the left of the door and go out to the stables. You can see the stunning symmetry of the stable’s pillars from three different perspectives. The granaries have such elegance and grace that they were once called the Cathedral of Grain by a group of Franciscan priests, who were so moved that they requested permission to sing religious chants here. Acoustically perfect, the granaries and surrounding parks are often used for summer concerts and receptions. They’re 2 km (1 mile) south of Moulay Ismail’s mausoleum, so take a taxi in hot weather.

Terrasse des Tanneurs – The Tanneries

The medieval tanneries are at once beautiful for their ancient dyeing vats of reds, yellows, and blues and unforgettable for the stinking smell of decaying animal flesh on sheep, goat, cow, and camel skins. The terrace overlooking the dyeing vats is high enough to escape the place’s full fetid power and get a spectacular view over the multicolor vats. Absorb both the process and the finished product on Chouara Lablida, just past Rue Mechatine (named for the combs made from animals’ horns): numerous stores are filled with loads of leather goods, including coats, bags, and babouches (traditional slippers). One of the shopkeepers will hand you a few sprigs of fresh mint to smother the smell and explain what’s going on in the tanneries below—how the skins are placed successively in saline solution, quicklime, pigeon droppings, and then any of several natural dyes: poppies for red, turmeric for yellow, saffron for orange, indigo for blue, and mint for green. Barefoot workers in shorts pick up skins from the bottoms of the dyeing vats with their feet, then work them manually. Though this may look like the world’s least desirable job, the work is relatively well-paid and still in demand for a strong export market.

Bou Inania Medersa

From outside Bab Boujeloud, you will see this medersa’s green-tile tower, which is generally considered the most beautiful of Kairaouine University’s 14th-century residential colleges. It was built by order of Abou Inan, the first ruler of the Merenid dynasty, which would become the most decisive ruling clan in Fez’s development. The main components of the medersa’s stunningly intricate decorative artwork are the green-tile roofing; the cedar eaves and upper patio walls carved in floral and geometrical motifs; the carved-stucco midlevel walls; the ceramic-tile lower walls covered with calligraphy (Kufi script, essentially cursive Arabic) and geometric designs; and, finally, the marble floor. Showing its age, the carved cedar is still dazzling, with each square inch a masterpiece of handcrafted sculpture involving long hours of concentration required to memorize the Koran. The black belt of ceramic tile around the courtyard bears Arabic script reading “This is a place of learning” and other such exhortatory academic messages.

Bab Boujeloud

Built-in 1913 by General Hubert Lyautey, a Moroccan commander under the French protectorate, this Moorish-style gate is 1,000 years younger than the rest of the medina. It’s considered the principal and most beautiful entry point into Fez el-Bali. The side facing toward Fez el-Djedid is covered with blue ceramic tiles painted with flowers and calligraphy; the inside is green, the official color of Islam—or peace, depending on interpretation.

Andalusian Mosque

This mosque was built in AD 859 by Mariam, sister of Fatima al-Fihri, who had erected the Kairaouine Mosque on the river’s other side two years earlier with inherited family wealth. The Almohads built the gate in the 12th century. The grandly carved doors on the north entrance, domed Zenet minaret, and detailed cedarwood carvings in the eaves, which bear a striking resemblance to those in the Musée Nejjarine, are the main things to see here, as the mosque itself is set back on a slight elevation, making it hard to examine from outside.

Medersa al-Attarine

Located next to the Qarawiyyin mosque in the middle of the medina, the other members are open to non-Muslims. Like the Medersa Bou Inania, ornate tile, stucco, and woodwork decorate this wonderful, nearly 1,000-year-old medersa. Ask if you can go upstairs to peek at the student quarters. (It is open all days except Friday; hours vary; 10 dhs.)

Fondouk el-Nejjarine

The Fondouk el-Nejjarine (also known as the “Wood Museum” and the Musée de Bois) faces the old Place el-Nejjarine or the “Carpenter’s Square.” The fondouk was constructed in the 18th century and originally served as a “caravanserai” or “roadside inn” for travelers and traders. A former minister spent 25 million dirhams (about 3 million USD) to restore this fondouk and transform it into the museum it is today. Visitors will want to spend an hour or so in this wonderfully restored building learning about the woodwork indigenous to Morocco, the tools used, as well as a collection of wood and cabinet work — both ancient, dating from the 14th century, as well as more modern pieces — from various regions in Morocco. Make sure you leave time to visit the rooftop terrace, one of the best views of Fez. A beverage will set you back 10dhs. (Open 10 am – 5 pm daily; 20 dhs).

Henna Souk

Many souks (usually a large square of shops) are interwoven throughout the medina, often blending into each other with little evidence you’ve moved from one souk to the other. However, toward the bottom of the medina, just off Trek K’beer, you can find the Henna Souk, a nicely shaded souk cozied up beneath a couple of large plane trees. Leo Africanus once worked in the now-defunct psychiatric hospital built in the 1,300s. Pottery and traditional cosmetic products can be found here, so if you want to grab argan oil or any other Moroccan goods, talk to Mohammed in the last cosmetic stall near the old hospital.

Batha Museum

Located in a Moorish palace dating from the 19th century, the Dar Batha Museum houses many artifacts, such as sculpted wood, plaster, jewelry, carpets, and pottery. 9 am-5 pm, closed Tuesdays and holidays, 10Dh.

Mellah

The Mellah, or Jewish Quarter, of Fez, was established in 1438. It is the oldest of the mullahs in Morocco, though very few Jewish people live here today, most of them having moved to Casablanca, France, or Israel. Today’s Mellah section is well worth a stroll, with ornate balconies and wrought-iron windows. There is an excellent view from the terrace of the Danan Synagogue on rue Der el-Ferah Teati, and the Jewish cemetery is worth a visit, though be wary of faux guides and people asking for money at the cemetery; it’s best to go with a knowledgeable guide if you want to avoid being hassled.