Mount Nemrut Travel Guide

Introduction

Mount Nemrut Travel Guide – Mount Nemrut, the monumental resting place of King Antiochus I Theos from the Kingdom of Commagene, is one of the most fascinating ancient places in Turkey. Although the country abounds in magnificent relics of antiquity, Mount Nemrut certainly deserves the place on the top ten list of the archaeological hits of Asia Minor. Moreover, the hierothesion of Antiochus is a sensational sight on a global scale. At the same time, it is an archaeological site that still holds many secrets. Until now, it has not been possible to determine with certainty what the artificial embankment on thttp://eskapas.com/best-historical-places-in-turkey/he peak of the mountain conceals. What’s more, astronomy enthusiasts can try to solve the mystery of the famous “lion horoscope” placed on one of the bas-reliefs decorating the mountain. Finally, the huge sculptures on Mount Nemrut are a perfect illustration of religious syncretism and Antiochus’ attempt to introduce a new state cult that combined Greek, Persian and Armenian influences.

Location

Set within the Anti-Taurus mountain range in southeastern Turkey , beyond the borders of Adiyaman, is the archaeological wonder of Mount Nemrut. Forgotten for centuries, the spellbinding peak of Nemrut Dagi (its Turkish name) has since managed to capture the imagination of thousands of visitors who come annually to witness the pure magic of its landscape at dawn and dusk, when the mighty stone heads glow gold . Mount Nemrut is located at the heart of what was the Kingdom of Commagene , a small kingdom that carved its place in history from the living rock. In 62 BCE, King Antiochus I (70 – c. 38 BCE), one of the megalomaniacal rulers of this small local dynasty, decided to leave an enduring monument to his greatness and ordered the construction of a tomb -sanctuary on the summit of Mount Nemrut.

Antiochus chose the highest mountain peak of his kingdom for his mausoleum. On its summit, at an altitude of 2,150 metres (7,000 feet), he built a high tumulus (artificial mound) that is still visible today in every direction from over 100 kilometres (62 miles) away. According to inscriptions left behind before he died, Antiochus wanted to be buried in a high and holy place among the gods. The king wished to be preserved for eternity, and by all accounts, he succeeded. However, it was only in 1881 CE that a German road engineer reported the tomb’s discovery. Since then, the site has been excavated by many native and foreign researchers. It became the world’s highest open-air museum and was included on the prestigious UNESCO World Heritage List in 1987 CE.

The Kingdom of Commagene

The ancient Commagene Kingdom occupied what had been Seleucid territory on the right bank of the Euphrates river. It consisted of the land between the plains of northern Syria and the eastern Taurus Mountains, the portion of southeastern Asia Minor that today roughly corresponds with Adiyaman Province and the north of Gaziantep Province. Its history begins with the reign of Ptolemaeus of Commagene (201-130 BCE), a Seleucid officer of Orontid Armenian descent who became king around 162 BCE and established himself as an independent ruler. His kingdom controlled the crossings of the Euphrates River from Mesopotamia and several routes over the Taurus Mountains. As a result, it played a significant role as a buffer state between the Seleucid Empire in the west and Parthia in the east. Ptolemaeus was succeeded by his son Sames II (r. 130-109 BCE), who founded the fortress at Samosata. According to the ancient Greek historian Strabo (c. 64 BCE – c. 24 CE), the kingdom became wealthy from trade and agriculture, particularly on the fertile lands around the capital. As part of a peace alliance between the Kingdom of Commagene and the Seleucid Empire, Mithridates I Callinicus (r. 109-70 BCE), the son and successor of Sames II, was married to the Seleucid princess Laodice VII Thea. Gradually, the kingdom became Hellenized, and Greek was adopted as the official language.

Commagene reached its height in the 1st century BCE under Antiochus I. During his long reign, the Romans waged war against the Parthians, and Antiochus allied himself with the Romans, before forming alliances with the Parthians by arranging the marriage of his daughter Laodice to Orodes II of Parthia (57-37 BCE). Commagene maintained its independence until its annexation by the Roman Empire in 17 CE. It re-emerged as an independent kingdom from 38 CE but was permanently absorbed into the Roman province of Syria in 72 CE when the emperor Vespasian (r. 69-79 CE) deposed Antiochus IV (38-72 CE) for his alleged conspiracy with the Parthians against the Romans.

Archaeological researches

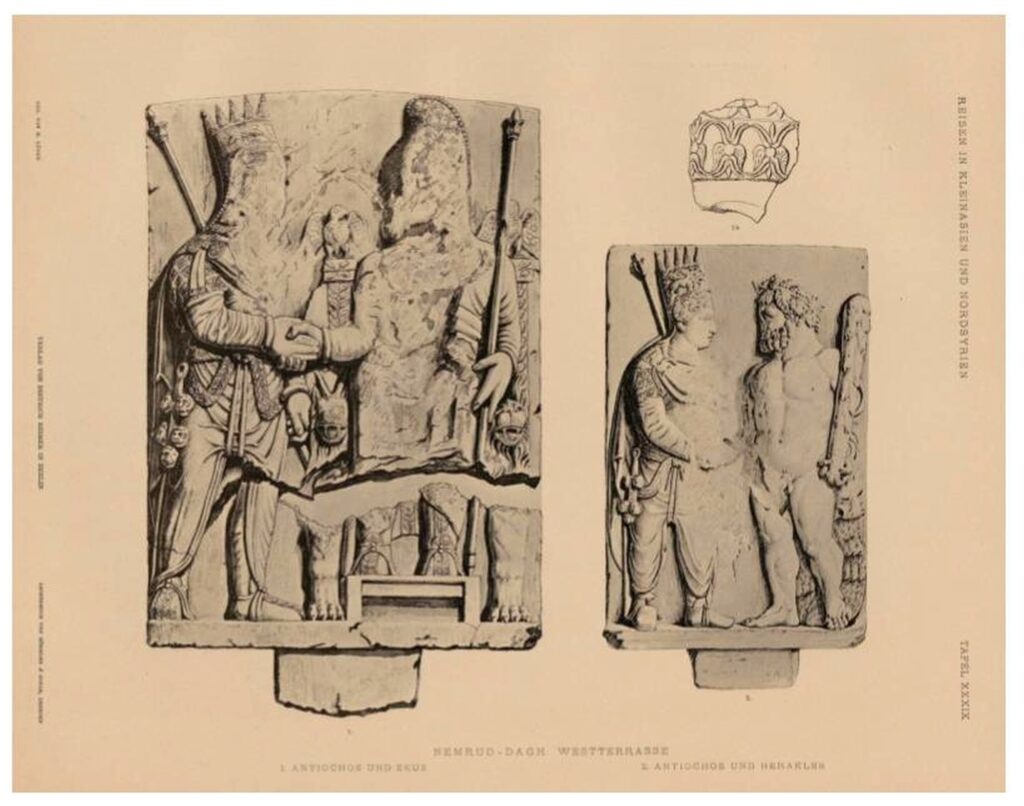

The existence of the remains of an ancient monument on Mount Nemrut has not been a secret for a long time. In 1881, a German engineer laying out transport routes in the Ottoman Empire, Karl Sester, reported on the unusual structures in Nemrut. Naturally, he was not brought the peak by sheer chance. Sester had planned to mark the route through eastern Anatolia based on the course of ancient communication routes. The inhabitants of the surrounding settlements who assisted him were unable to show him any ancient road but were happy to inform him about extraordinary monumental statues on Mount Nemrut. Motivated more by pure curiosity than the real possibility of marking the road through this mountain peak, Sester climbed to the top in the company of a Kurd named Bâko, and he saw monumental sculptures with his own eyes. Shortly afterwards, the first scientific expeditions set off to Mount Nemrut. In 1882, the German Archaeological Institute delegated Otto Puchstein, an archaeologist who was on a mission in Egypt, to visit Nemrut in the company of Sester. A year later, Puchstein returned to the mountain with Karl Humann. In the same year, the first Turkish research mission arrived at Nemrut, under the direction of archaeologist Osman Hamdi Bey and sculptor Osgan Effendi. However strange this may sound, the vast part of the knowledge we now have about the hierothesion on Mount Nemrut comes from that pioneer period of research. It was Sester and Puchstein who discovered a very long inscription in Greek, which informed about the purpose of erecting the monument and the intentions of Antiochus. German and Ottoman researchers made detailed descriptions of all the finds visible above the ground and translated the inscription. The results of these first studies became available to the general public already in 1890, when an extensive publication devoted to Mount Nemrut, authored by Humann and Puchstein, was released in Berlin. In turn, Turkish researchers published the results of their work in the book “Le Tumulus de Nemroud Dagh” published in French in 1883. Nevertheless, these pioneering studies did not include excavation works. The researchers lacked technical means to remove the thick layer of rubble that had slipped from the top of the tumulus and covered the fragments of monumental statues.

Despite the sensational discovery, Mount Nemrut had to wait more than half a century to arouse the interest of the researchers again. In 1939, Friedrich Karl Dörner, the author of the doctoral dissertation on the Kingdom of Commagene, arrived in eastern Anatolia and began systematic research of this mountain. After a break caused by the outbreak of the Second World War, Dörner returned to Nemrut, not only to reveal its secrets but also to discover other archaeological sites from the times of the Commagene Kingdom. To him we owe the exploration of Karakuş Tumulus, resulting in the discovery of a hidden burial chamber, the identification of the summer capital of Commagene – Arsameia on the Nymphaios, and the second Arsameia – on the Euphrates.

Visiting the Sanctuary

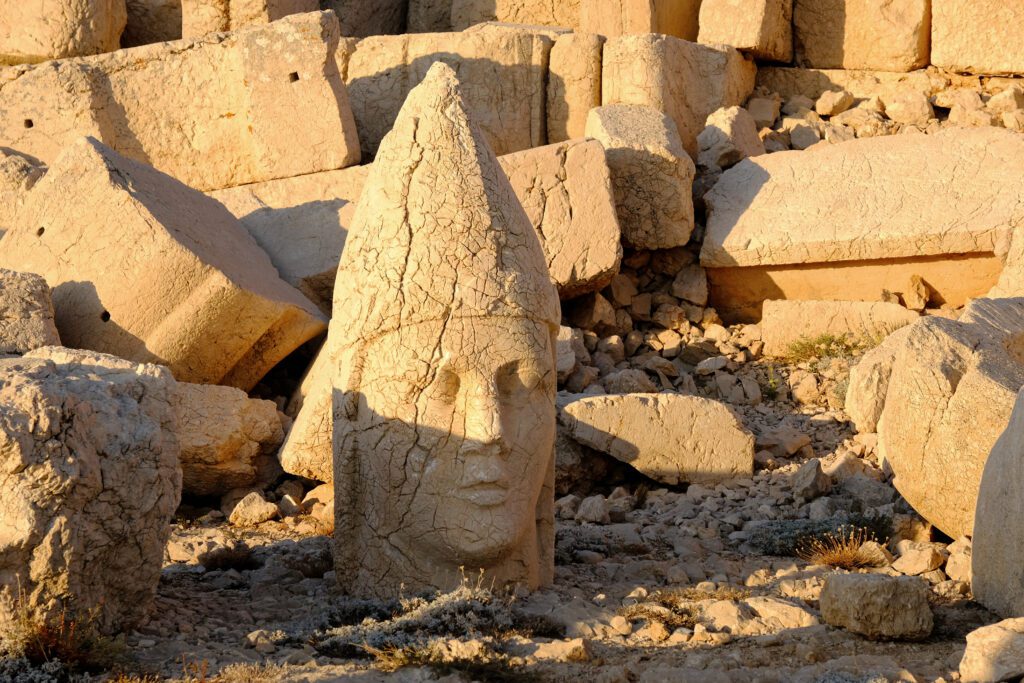

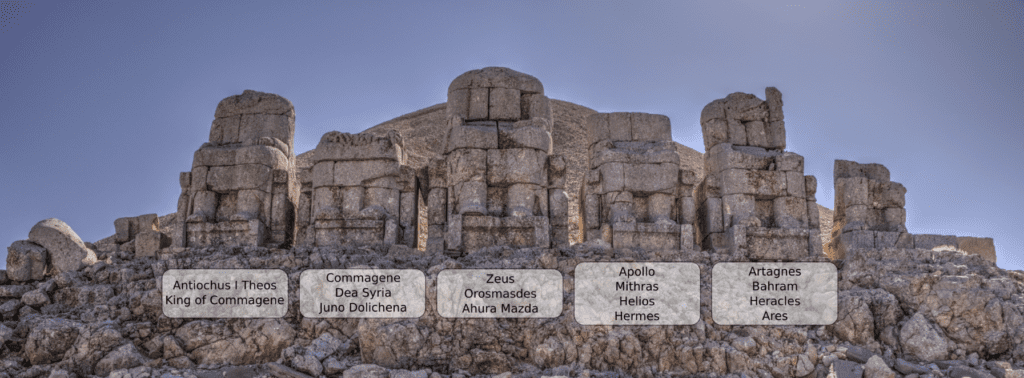

Visitors access the different terraces via a narrow processional way around the base of the tumulus. The east and west terraces lie on either side and are both dominated by a row of five colossal enthroned statues. Sitting majestically with their back to the tumulus, the figures, between 8 and 10 metres (26-32 feet) tall, have been identified as Antiochus I and a pantheon of Greek, Armenian, and Persian deities that reflected Antiochus’ mixed ancestry – Zeus -Orosmasdes- Ahura Mazda , Artagnes-Bahram- Hercules – Ares , Apollo – Mithras- Helios – Hermes , and Commagene- Atargatis- Juno Dolichena.

Their stone heads, tossed to the ground by earthquakes, have been rearranged to help visitors understand who they were. King Antiochus is seated on the left end side. He is dressed in Persian garb and wears an Armenian tiara, while the gods are represented in assorted Greek and Persian apparel. Apollo-Mithras-Helios-Hermes, for example, wears Persian clothes. The goddess Commagene is dressed in the Greek style and holds a cornucopia filled with fruits and flowers (symbolizing the fertility of the kingdom). The blending of eastern and western cultures follows the principle known as syncretism that was propounded by Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE) and his successors to help bind the peoples of the former Persian Achaemenid Empire with their Greek conquerors. The enthroned gods were flanked on either side by larger-than-life statues of guardian creatures, a lion and an eagle, and by a group of sandstone slabs representing hand-shaking (dexiosis) scenes of the king with the different deities. Two rows of stelae completed the monument with portraits of Antiochus’ Achaemenid and Hellenistic ancestors.

East, West, & North Terraces

The East Terrace is the best-preserved. The colossal enthroned statues stand on a tiered podium, some 7 metres (22 feet) above the terrace, facing toward the sunrise. On the back of these statues, a long inscription carved in Greek details the historical and legal aspects regarding the sanctuary and the establishment of the new cult. Opposite the seated statues are the foundations of what is believed to be a sacrificial altar. The West Terrace had the same features as those displayed on the East Terrace but was considerably narrower than its eastern counterpart and had no main altar. It is now also more damaged, although the colossal heads are better preserved. The order of the enthroned statues, this time facing the setting sun and standing only 2 metres (6.5 feet) above the terrace, is identical to those of the East Terrace. Alongside the great statues, five superb cult reliefs have survived.

Three of them represent dexiosis scenes showing Antiochus shaking hands with Apollo, Zeus, and Hercules, while the fifth one, the finest, is thought to represent a kind of horoscope, one of the oldest known in the world. It depicts a lion with 19 stars, signifying the constellation Leo, three planets (identi³ed by Greek inscriptions as Mars , Jupiter , and Mercury) and a crescent moon (representing Commagene). Recent research has shown that the lion relief may reflect the situation of the skies at particular events like the coronation of Mithridates I in 109 BCE and his son Antiochus in 62 BCE. All the reliefs have been removed from the site and are stored in the Adiyaman Archaeological Museum. On the far side of the terrace are reliefs of Antiochus’ paternal ancestors, who linked him with the Achaemenid royal house. Between the East and West terraces is the 86-metre-long (282 feet) North Terrace. It is quite narrow and was probably never ³nished as the stelae lying nearby are all unworked, bearing no inscriptions or figures. There is also no statue. Some scholars have advanced the possibility that this terrace was allocated for the use of kings who would take the throne aëer Antiochus. However, Antiochus’ son, Mithridates II (c. 38-20 BCE), probably decided to halt construction projects on Mount Nemrut and instead turned to his own initiatives, such as the construction of the burial monument at Karakus.

Lion Horoscope

Where can you see the famous “Lion Horoscope” now? Its story resembles the last scene from the movie The Raiders of the Lost Ark, in which the hard-to-find Ark of the Covenant, recovered by Indiana Jones, is safely stored in a huge warehouse. After Osman Hamdi Bey discovered the lion relief in 1882, it remained for a long time in the place where he had been found. In 1984, during his last visit to Nemrut, Dörner set it upright along with blocks depicting dexiosis scenes on the West Terrace, after reinforcing them with concrete and epoxy resin. However, these reliefs were overturned in 2002, under the pressure of snow sliding down from the peak of the tumulus. Shortly afterwards, in 2003, four steles depicting dexiosis and the lion relief were transported to the Temporary Restoration Laboratory due to their bad state of preservation, and have remained there until today.