Fisherman of Halicarnassus

If you come to the top of this hill, you will see Bodrum. Don’t think that you will leave the same person as when you arrived. To all those who came before you, it happened that way: they lost their hearts in Bodrum.”

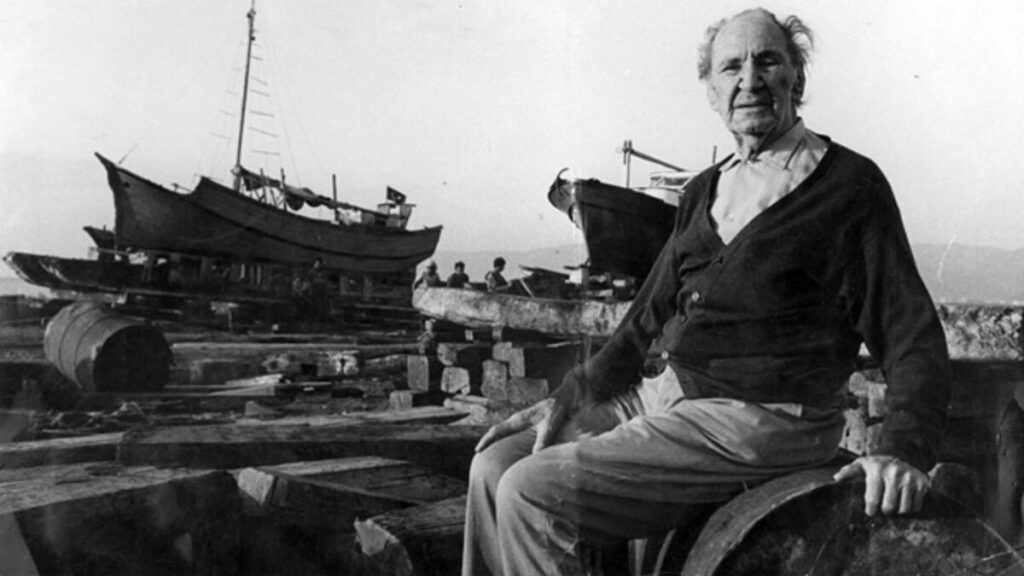

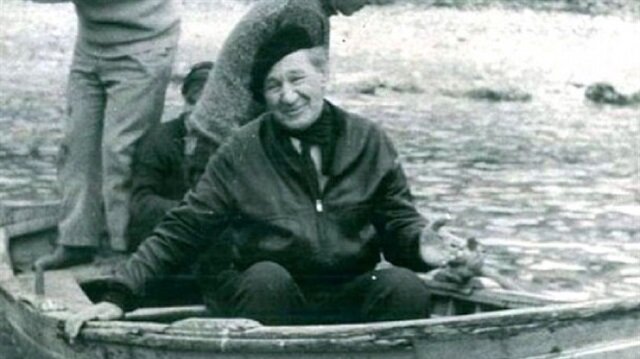

This quotation is the first thing visitors see on the main road into Bodrum. It is written large on a sign of welcome erected by the town council with a photograph of the smiling, weather-battered face of its author. He is Cevat Şakir Kabaağaçlı, known as ‘Halikarnas Balıkçısı’, the Fisherman of Halicarnassus, and his name will crop up again and again on a visit to the town he is credited for turning into Turkey’s most famous resort.

His words in praise of Bodrum and its blue waters find their way on to every scrap of travel literature, on walls of hotels, and even on paper tablecloths set out for breakfasts. His bust is outside the castle and it sits in a memorial garden in Cevat Şakir Caddesi, the main street, where the Bodrum Maritime Museum has a corner dedicated to his life.

The Fisherman lost his heart here when he arrived in 1925 as a prisoner, sentenced to internal exile by a tribunal of the new Turkish Republic for something he had written. He found and fell in love with what was then an impoverished village of fishermen and sponge divers, of narrow lanes trudged by camels and donkeys where people went to bed when the sun went down, and he stayed to see it become a fashionable and lively summer resort that today likes to party till dawn.

Cevat Şakir was an Oxford-educated writer and artist from the upper stratum of Ottoman society. What caused him to take up his pen-name was life in the community that he encountered here, a life far removed from the one into which he had been so fortunate to have been born. Here the people, like their ancestors, “could look on things unperturbed by cant and prejudice – just the naked eye of man gazing on nature”.

His stories gained him a wide national readership, but he became involved in the community, too, improving fishing techniques and planting trees in public spaces. He has even been described as ‘the first ecologist’. In the 1950s and 1960s literary and artistic friends came to see him, and to join him in the simple summer adventures he had been enjoying for more than two decades, sailing with minimal provisions and equipment around the Gulf of Gökova and along the Carian and Lycian coasts. Soon these ‘Blue Voyages’ or ‘Blue Cruises’ began to appear in holiday brochures that put Bodrum on the map and brought the first adventurous travellers from abroad, so that in time many of the fishermen who had inspired the Fisherman were able to hang up their hooks, stow their nets and find employment in the more lucrative and less perilous tourist trade.

This coast is the meeting point of the Aegean and Mediterranean seas. Into their blue waters tumble the last folds of the majestic Taurus mountains that rise over the Mediterranean littoral of Lycia before drifting down to the shore in myriad bays and islands. On the west coast, mountain ranges run parallel with the shore and there are few entry points into the interior. It is these mountains that helped to keep the coast cut off for centuries, leaving Anatolia’s exceptionally rich plant life to bury countless layers of Classical civilisations.

Here is to be found the densest concentration of Greco-Roman remains in the world. The province of Muğla, in which Bodrum resides, has no fewer than fifty-seven sites, more than any other in Turkey. There is such a proliferation of rock tombs, temples, arenas, theatres, necropolises and city foundations that even in the 21st century many acres remain in desperate need of archaeological investigation.

Halicarnassus, the ancient name for Bodrum that predates the Greeks, was an important city, the capital of Caria, and famous for the enormous tomb of its ruler, Mausolos, which became one of the Seven Wonders of the World. Ephesus, which possessed another Wonder, lies to the north; the island of Rhodes, to the east, had a third.

By seeing Anatolia from the coast, as the travellers of antiquity had done, the Fisherman and his friends identified many sites that archaeologists would subsequently come to explore. These discoveries led Cevat Şakir to believe that Anatolia was the wellspring not just of Classical Greek culture, but of all Western civilisation. He eventually settled to the north of Bodrum in Izmir (Greek Smyrna), Aegean Turkey’s main city, where he became the country’s first professional tourist guide. It was in this city, he liked to recall, that his hero Homer was most probably born. His epic poems that chronicled the siege of nearby Troy in the Iliad and Captain-King Odysseus’s subsequent adventurous homeward voyage in the Odyssey, were texts that Şakir returned to again and again.

As the Fisherman of Halicarnassus, he wrote extensively on the legacy of Asia Minor, which the West calls Anatolia, the Greek for ‘east’. In Turkish it is Anadolu. The Fisherman’s thoughts were synthesised through voyages with his friends who joined him in Bodrum on his Blue Voyages, and between them they developed a philosophy that combined classical literature with nature, mixed in with a belief in the common ‘folk’ to arrive at ‘Blue Anatolian Humanism’. Though they were not involved in politics, their beliefs brought them into conflict with the authorities and they all at some point found themselves in jail.

Even before the extraordinary events of his life unfolded, both happiness and tragedy seemed to be etched in Cevat Şakir’s features, as his young sister, Fahrelnisssa, recalled in her diary after one of his visits from Oxford: “He had the oddest face. The upper part seemed to be crying, while the lower part looked as though it were laughing. It was as if one had cut out the top part of a tragedy mask and glued it to the bottom of a comedy mask.”

He aged well. In 1977, four years after Cevat Şakir’s death, the journalist Ian Crawford wrote a piece in New Scientist recalling an encounter a few years earlier in Bodrum, where he found the Fisherman “lying on his boat in the bay with the tiller between his feet…a handsome old man, who spoke seven or eight languages with commanding fluency, wit and erudition. He talked of Homer as if he had just left him in a pub down the road, of how the hexameter had been born of a dance rhythm formed with the fingers of one hand, and of Pegasus on a petrol station sign blushing from head to toe at being used in an advertisement.”

Mentions of the Fisherman of Halicarnassus in an English publication are rare. Though he is still highly regarded in Turkey, where his books – five novels, eleven books of short stories and eleven books of essays – sell around 2,000 copies a year (not including pirated copies), it is hard to find any of his work in translation. In 1993, twenty years after his death, a fictionalised film of Mavi Sürgün (Blue Exile), Cevat Şakir’s own story of his banishment to Bodrum, was made by the Turkish director Erden Kıral.

This book is not a biography or a literary critique. It is a guide book for modern Blue Voyagers (Google it you will find many online seller) , a small volume to take on board to dip in and out of, to fill in a few key facts about Turkey and about just a few of almost fifty civilisations that have flourished here, and to give a flavour of Cevat Bey and the waters he sailed. In the process it attempts to answer the question any tourist arriving in Bodrum may well ask. Who exactly was this Homeric figure called the Fisherman of Halicarnassus? Why was he so anxious to welcome visitors to Bodrum? And what can he tell us about Turkey and Blue Voyages today?