Caravanserais in Turkey

Introduction

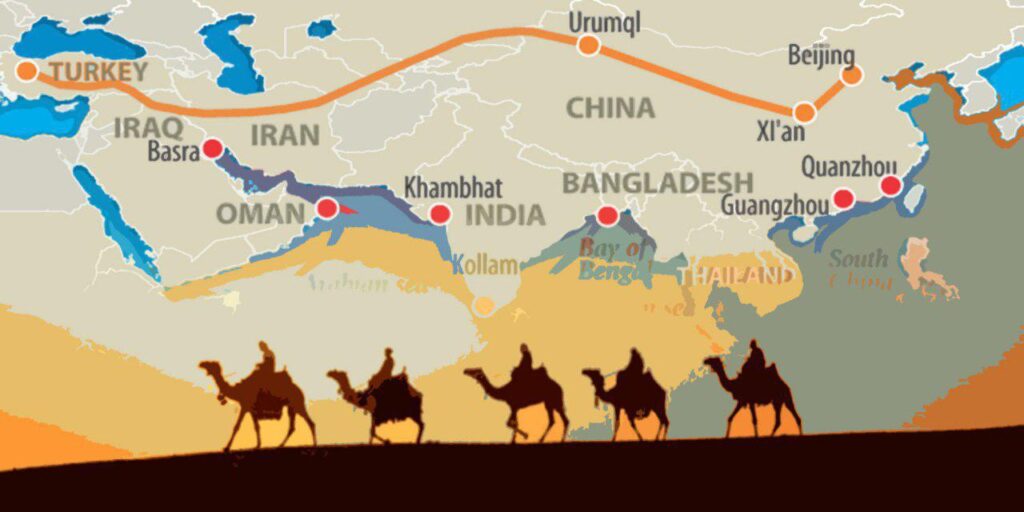

Caravanserais in Turkey – The Silk Road was a network of trade routes connecting the East and the West in ancient and Medieval times. The term is used for both overland routes and those that are marine or limnic. The Silk Road involved three continents: Europe, Africa and Asia. In addition to silk, a wide range of other goods was traded along the Silk Road, and the network was also important for migrants and travelers, and for the spread of religion, philosophy, science, technology, and artistic ideals. The Silk Road had a significant impact on the lands through which the routes passed, and the trade played a significant role in the development of towns and cities along the Silk Road routes. Many merchants along the Silk Road were involved in relay trade, where an item would change owners many times and travel a little bit with each one of them before reaching its final buyer. It seems to have been highly unusual for any individual merchant to travel all the way between China and Europe or Northern Africa. Instead, various merchants specialized in transporting goods through various sections of the Silk Road.

The inland routes of the Silk Roads were dotted with caravanserais, large guest houses or hostels designed to welcome travelling merchants and their caravans as they made their way along these trade routes. Found across Silk Roads countries from Turkey to China, they provided not only a regular opportunity for merchants to eat well, rest and prepare themselves in safety for their onward journey, and also to exchange goods, trade with to local markets, and to meet other merchant travelers, and in doing so, to exchange cultures, languages and ideas. As such, caravanserais were far more than simply watering holes along the Silk Roads; they developed as crucibles for the cross-fertilization of cultures along the length of these routes.

Best of Turkey and Greece with 3-night cruise (With flight from USA – Small Group)

Discover your perfect Turkey vacation package using our convenient search and filter options, tailor-making a journey that captures Turkey’s unique beauty and rich heritage just for you.

Etymology

There is relatively little known about the origins of the caravanserai. Etymologically, the word is a compound of the Persian kārvān, meaning caravan or group of travelers, and sara, a palace or enclosed building, with the addition of the Turkish suffix -yi. One of the earliest examples of such a building can be found in the oasis city of Palmyra, in Syria, which developed from the 3rd century BC as a place of refuge for travelers crossing the Syrian desert. Its spectacular ruins still stand as a monument to the intersection of trade routes from Persia, India, China and Roman Empire. As trade routes developed and became more lucrative, caravanserais became more of a necessity, and their construction seems to have intensified across Central Asia from the 10th century onwards, particularly during periods of political and social stability, and continued until as late as the 19th century. This resulted in a network of caravanserais that stretched from China to the Indian subcontinent, Iran, the Caucasus, Turkey, and as far as North Africa, Russia and Eastern Europe, many of which still stand today.

Historical overview

The Seljuk sultans who ruled over the central regions of Asia Minor in the 12th and 13th centuries, ordered the construction of many caravanserais, both along the famous Silk Road, as well as on other important trade routes. The money flowed from the state treasury not only for the construction of these inns but also to compensate for the merchants who were assaulted and robbed during their journeys. Foreign merchants enjoyed a discount of customs duties. With such support, trade in Anatolia flourished. All the travelling merchants, regardless of their origin, could use the caravanserais. They had guaranteed free food and drinks for the first three days of their stay. They also had the medical care and help with pack animals. Each caravanserai employed an innkeeper, a doctor, a veterinarian, a blacksmith, a cook and an imam to ensure full services for travelers.

Cappadocian caravanserais, located on the Silk Road, were built with volcanic rock. Their walls are thick and very high, providing protection against the attacks of bandits. The most decorative elements of these buildings were their portals i.e. door frames. They represent the finest examples of Seljuk stone sculpture. The doors placed in these portals were made of iron. Most of the Seljuk caravanserais were built during the reign of two sultans: Kılıç Arslan II, who reigned from 1156 to 1192, and Alaaddin Keykubat I, known for the expansion of Alanya, who ruled from 1220 to 1237. However, the Yellow Caravanserai was built later, when Izzettin Keykavus II was the Seljuk sultan (1246-1257), perhaps even on his direct orders.

Grand Service for Travelers

Caravanserais were ideally positioned within a day’s journey of each other, so as to prevent merchants (and more particularly, their precious cargos) from spending nights exposed to the dangers of the road. On average, this resulted in a caravanserai every 30 to 40 kilometers in well-maintained areas, such as along the Great Trunk Road that ran through northern India and into Pakistan. Additionally, some had fortified walls and doubled as military strongholds or outposts, known as rabats, particularly those positioned near frontiers or borders. They also played a role in communicating both regional and international news across Central Asia, and for instance, under the Mughal emperors of the 16th century, the caravanserais of the Great Trunk Road in northern India were supplied with messenger horses, ready to pass on any important news carried by travelers.

However, perhaps the most important legacy of the caravanserai was its role as a crucible for the exchange and interaction of cultures along the length of the Silk Roads. Not only did they facilitate the movement of people and goods along these long and arduous routes, they also provided opportunities for these travelers to come together, to share stories and experiences, and ultimately, cultures, ideas and beliefs too. Languages had to be learnt in order to be able to communicate stories from the route, and local food, clothing and etiquette was combined with merchants’ own goods and customs. Moreover, religions, traditions and ideas rubbed shoulders in such places, and brought influences from along the lengths of the Silk Roads into the communities around the caravanserais. Many were furnished with mosques as Islam spread through Central Asia in the early middle ages, and Buddhism, Christianity and Judaism were also transmitted by religious scholars travelling along these routes. The traces of such exchange are reflected in the diverse yet closely interrelated cultures that have emerged along the Silk Roads and the plurality of languages and religions that have flourished throughout this region of the world. Cities that contained caravanserais became great intellectual and cultural centers, such as Samarkand, Qazvin, Bursa, Aleppo, and Acre, and those that lay along isolated highways became local centers of civilization.

Silk Road Caravanserais in Turkey

The Seljuk Empire of Anatolia spanned the ancient trade routes of Anatolia, the camel trails along which the riches of Persia and China had been carried to the markets of Europe, and vice-versa. With trade came wealth, so the Seljuk sultans and the grandees of the empire worked to encourage, increase and protect commerce by road. The great men and women of the empire endowed hans, or kervansarays (“caravan palaces”) along the Silk Road and other major routes. These huge stone buildings were made to shelter the caravaneers, their camels, horses and donkeys, and their cargoes, to keep them safe from highwaymen and to provide needed travel services.

The typical Seljuk caravanserai is a huge square or rectangular building with high walls of local stone. The walls are smoothly finished but devoid of decoration. Supporting towers or buttresses may be in geometric shapes (half-cylinder, half-octagon, half-hexagon, etc) and the outlets for roof runoff may be stylized animal heads, but otherwise the exterior is severely plain. The exception is the main portal, which is elaborately decorated with bands of geometric design, Kur’anic inscriptions in Arabic script, and the sculpted geometric patterns of mukarnas (stalactite vaulting).

The internal structure of the caravanserai facilitated this process of interaction, not least through the provision of hamams and bazars, providing further opportunities and incentives for travellers to relate to one another. Indeed, trading began at such places too, and often the market held within the caravanserai was the first occasion for merchants to start to sell their produce. In larger caravanserais with two entrance gates, bazars would run through the centre of the entire compound. These would be supplied by the merchants who had arrived at the site, and those that were situated near cities would often feed into regional markets too. Such points of practical and commercial trade consolidated the more intangible and yet, in some ways even more profound, exchange that characterized these oases of hospitality along the Silk Roads.

The existence of this network of caravanserais along the Silk Roads thus provided a foundation for the new cultures that were to spring up alongside these routes. Scattered in their thousands across Central Asia, they not only provided safety and rest to the merchants that traversed these routes, but were of great economic, social and cultural significance to the regions in which they were based. Bringing travelers together from east and west, they facilitated an unprecedented process of exchange in culture, language, religion and customs that has become the basis of many of the cultures of Central Asia today.

Walk through the main portal and you pass the room of the caravanserai’s manager and enter a large courtyard. At its center may be a mescit (small mosque or prayer-room), usually raised above ground level on a stone platform. (The mescit may also be built into the walls above the main portal.) Around the sides of the courtyard, built into the walls, are the service rooms: refectory, treasury, hammam (Turkish bath), repair shops, etc.

At the far end of the courtyard from the main portal is the grand hall, a huge vaulted hall usually with a nave and three side aisles. The hall is usually lit by slit windows in the stone walls and/or a stone cupola centered above the nave. The hall sheltered goods and caravanners during bad winter weather. Most caravanserais were built as pious endowments: a wealthy Seljuk gave money for the building’s construction and also made available a source of income to be used for its maintenance. Caravans were received into the caravanserai each evening, and were welcome to stay free for three days. Food, fodder and lodging were provided free of charge, courtesy of the building’s founder. (Most caravans probably moved on the next morning.) Nearly 100 Seljuk caravanserais still exist along the Silk Road and other routes in former Seljuk lands. Many are in ruins, but some are well preserved and real treats to visit and explore.

Main Caravanserais

The richest concentration of hans is along the Silk Road from Aksaray east to Nevşehir and Avanos: Ağzıkarahan, Tepesidelik Han, Alay Han, Sarı Han and more. The Sultan Han, grandest of all, is west of Aksaray on the Konya highway. Another Sultan Han and the fine Karatay Han are east of Kayseri.

Sultanhanı Caravanserai

Sultanhanı is a large 13th-century Seljuk caravanserai located in the town of Sultanhanı, Aksaray Province, Turkey. It is one of the three monumental caravanserais in the neighbourhood of Aksaray and is located about 40 km (25 mi) west of Aksaray on the road to Konya. The caravanserai is considered one of the best examples of Seljuk architecture in Turkey. Covering an area of 4,900 square meters, it is the largest medieval caravanserai in Turkey.

The khan is entered at the east, through a pishtaq, a 13-m-high gate made from marble, which projects from the front wall (itself 50 m wide). The pointed arch enclosing the gate is decorated with muqarnas corbels and a geometrically patterned plaiting. This main gate leads into a 44 x 58 m open courtyard that was used in the summer. A similarly decorated archway on the far side of the open courtyard, with a muqarnas niche, joggled voussoirs and interlocking geometric designs, leads to a covered courtyard (iwan), which was for winter use. The central aisle of the covered hall has a barrel-vaulted ceiling with transverse ribs, with a short dome-capped tower over the center of the vault. The dome has an oculus to provide air and light to the hall. A square stone kiosk-mosque (köşk mescidi), the oldest example in Turkey, is located in the middle of the open courtyard. A construction of four carved barrel-vaulted arches supports the mosque on the second floor. The small prayer hall of the mosque contains a richly decorated mehrab (Qibla direction marker), and is lit by two windows. Stables with accommodation above were located in the arcades on both sides of the inner courtyard.

Agzikarahan Caravanserai

The caravanserai is considered one of the most important and richly-decorated examples of ordinary caravanserais built by non-royal patrons. Foundation inscriptions attest that the covered/roofed section of the building was completed in June 1231 during the reign of Sultan Ala ad-Din Kayqubad I, while the courtyard was completed in February 1240 during the reign of his successor Kaykhusraw II. The patron who commissioned the construction was named Mes’ud, son of Abdullah. Like other major caravanserais of this period, it consists of two sections: one centered around a main courtyard, and an indoors section. The caravanserai is entered via a monumental entrance portal projecting from the plain exterior walls of the building, with stone-carved decoration and a vaulted canopy of muqarnas. It leads to the main courtyard, around which are numerous chambers. In the middle of the courtyard is a small mosque consisting of a square stone chamber raised on four pillars and reached by stairs, considered an excellent example of this feature (which recurs in other caravanserais). The indoors section consists of a vaulted nave with a central dome (though the dome itself has been lost), from which vaulted chambers open on either side

Sarı Han(Saruhan) Caravanserai

An impressive building of Yellow Caravanserai, referred to in Turkish as Sarı Han or Saru Han, stands on the outskirts of Avanos. Its name, as you might imagine, comes from the color of stone blocks that were used for its erection in 1249. Yellow Caravanserai owes its present appearance to a thorough renovation, carried out in 1991. Travelers visiting Cappadocia usually have the opportunity to visit this caravanserai, if they decide to participate in sema ceremony that is the show of famous whirling dervishes.

The caravanserai is situated on the banks of the Damsa Creek, and its gate is facing west. It was built from blocks of volcanic rock in three colours – yellow, beige, and pink. These colours were used to obtain a decorative effect on the arches of external and internal portals. What’s interesting – a small mosque (tr. mescit) is located above the main gate. This architectural solution distinguishes Sarı Han from other buildings of this type because the prayer room was usually placed in the middle of the courtyard. The building covers an area of approximately two thousand square meters, and its central part is the vast courtyard. To the left, looking from the entrance, there are six open spaces covered with vaulted arches. On the right side, there are roofed rooms, also with ornately carved portals. Opposite the entrance, there is another richly decorated portal, leading to a darkened and spacious room, which hosts the shows of whirling dervishes. This room is covered with a hemispherical dome, with small holes providing sparse interior lighting. In 1991, the caravanserai underwent an extensive renovation, as it had been partly ruined. The impact of this improvement arises mixed feelings – some commentators are delighted with the achieved result and call Sarı Han the most impressive of the Seljuk caravanserais, and others – are mourning the lost soul of the original building.

Frequently Asked Questions FAQs About Caravanserais in Turkey

Do caravanserais still exist?

What are three characteristics of a caravanserai?

What are the best tours best guided tours that visit one caravanserai in Turkey

- Asia Minor Western Promises | 7 Days

- Turkey Western Tour | 10 Days

- Turkey Western Tour | 8 Days

- Anatolian Legacy | 8 Days

- Best of Turkey and Greece with 2 days cruise

What are caravanserai also called?

Often located along rural roads in the countryside, urban versions of caravanserais were also historically common in cities throughout the Islamic world, and were often called other names such as khan, wikala, or funduq.

What were caravanserais made of?