Istanbul Archaeology Museums

Istanbul Archaeology Museums (Map) actually consists of three museums in one complex: the Museum of Ancient Orient (Eski Şark Eserleri Müzesi), the Tiled Pavilion Museum (Çinili Köşk Müzesi) and the Archaeology Museum (Arkeoloji Müzesi) itself residing in the main building. The main building was commissioned by archaeologist and painter Osman Hamdi (1881-1910). Late 19th century, the museum was founded to stop the flow of artifacts from the empire to Europe and house his discoveries. Osman Hamdi became the museum director. Soon after the inauguration, local governors spread out over the Ottoman Empire sent in a huge amount of objects. Today the museums have one of the world’s richest collections of classical artifacts on display.

Istanbul’s Archaeological Museum contains an important and beautifully presented collection of prehistoric, Greek, Roman, and Byzantine antiquities, which all come from the Topkapi Palace collections. Along with the nearby Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, this is the city’s top museum attraction and it should be high on the list of things to do for history-loving tourists.

Main Collection

The main building, with its imposing Neoclassical façade, houses the museum’s major treasures. Among the principal exhibits are the finds brought back from Lebanon by Ottoman archaeologist Osman Hamdi Bey. The rich treasure trove of sarcophagi he unearthed in Sidon (in south Lebanon) is from ancient Sidon’s royal necropolis. In particular, the magnificent Alexander Sarcophagus, with its intricate depiction of the Macedonian army battling the Persians, and the Sarcophagus of the Mourners, with 18 figures of mourning women, are gorgeous examples of the rich grave art of the 4th century BC.

As well as the Sidon cache, the collection includes sarcophagi found throughout the Ottoman Empire. The most exceptionally beautiful examples are the 5th-century BC Sarcophagus of the Satrap, the Lycian Sarcophagus (ca. 400 BC), and the 3rd-century Sidamara Sarcophagus from Konya. There are also some fine funerary stele and inscribed stones. Away from the tombs, there are also exhibits covering Troy and Anatolia, Cyprus, and Syria, and a vast coinage collection.

The building was initially built in 1881 by Osman Hamdi Bey specifically to house the collection, though it wasn’t until 1908 that it gained its present form. It’s renowned as the city’s most prominent example of Neoclassical architecture.

What not to miss at the Archaeology Museum

The Archaeology Museum is located in the biggest building in the complex and consists of four floors:

- ground floor: (of the old building) classical archaeology, featuring a collection of Hellenic, Hellenistic and Roman statuary and sarcophagi (in the old building). Don’t miss:

- a Roman statue of Bes, half-god of inexhaustible power and strength and the protector against evil.

- a group of sarcophagi from the Royal Necropolis of Sidon, unearthed in 1887

- the Alexander Sarcophagus (4th century B.C.), depicting him battling the Persians as well as a hunting scene

- the Sarcophagus of the Mourning Women

- ground floor: Thracian, Bithynian and Byzantine collections and the children’s museum, containing a huge Trojan Horse they can climb into

- first floor: Istanbul through the ages. A nice chronological overview of Istanbul’s archaeological past. Don’t miss:

- one of the three bronze snake heads from the now headless Serpentine Column at the Hippodrome

- a part of the iron chain hung across the Bosphorus and the Golden Horn during the Byzantine Empire to stop hostile ships form entering

- a bell (14th century) from the Galata Tower

- second floor: collections from Anatolia and Troy

- third floor: Anatolia’s neighboring cultures, a gallery devoted to Cyprus and Syria-Palestine

The Lycian Sarcophagus

The Lycian Sarcophagus, which depicts scenes from Greek mythology as well as griffons, centaurs, and sphinxes. This is the so-called “Lycian Sarcophagus” from the Royal Necropolis of Sidon (in modern Lebanon). The necropolis, belonging to line of Phoenician kings from middle of the fifth century BCE to the latter fourth century BCE, was discovered in 1887 by a Lebanese villager who was digging a well. Although from Sidon, this sarcophagus resembles the Lycian sarcophagi (hence the name) which can be found in Anatolia. This side of the sarcophagus depicts five mounted hunters in Thracian attire.

The Alexander Sarcophagus

The Alexander Sarcophagus that is covered in scenes of the Alexander the Great, but is actually believed to hold Abdalonymus, the king of Sidon.It is a 4th century BCE sarcophagus adorned with bas-relief carvings of Alexander (“the Great”) engaged in various violent activities. Contrary to popular belief, this is not the sarcophagus of Alexander himself (who was buried in Alexandria, Egypt), but probably that of Abdalonymus, Alexander’s appointee to the kingship of Sidon.

Serpent Column Head

This is one of the three serpent heads from the so-called Serpent Column (located in the Hippodrome). Originally from the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, the column commemorated the victory of thirty-one Greek city-states over the Persians at the Battle of Plataea (479 BCE). The bronze serpents are said to have been made from the shields of fallen Persian soldiers. Constantine I (“the Great”) removed the column from Delphi and planted it in the courtyard of Hagia Sophia, where it stood before being moved to the Hippodrome in the 9th century CE. The three serpent heads vanished during the Ottoman period (allegedly removed by a Polish diplomat in April of 1700). This one was rediscovered in 1847 and is now in the Archaeological Museum.

Other Exhibitions

The Istanbul Through the Ages exhibition, which gives a good overview of the history of this complex city. Look out for a section of the chain used to block access to the Golden Horn during Byzantine times. The Istanbul Troy museum in the Anatolia and Troy through the Ages collections are worth seeing, and contain many artefact discovered at famous site.

Museum of Ancient Oriental Art (Eski Sark Eserleri Müzesi)

Across the courtyard from the main museum building, this section of the collection is devoted to exhibits of pre-Islamic artistry. The artifacts here span the Middle East, from Ancient Egypt to Mesopotamia, and range from Assyrian and Hittite cuneiform tablets to Pharaonic statuary. The major highlight for most visitors is the ancient Babylon exhibit, which includes the glazed brick panels from Babylon’s Ishtar gate. The building itself was built in 1883 and was first used as Istanbul’s school of fine arts.

What not to miss at the Ancient Orient Museum

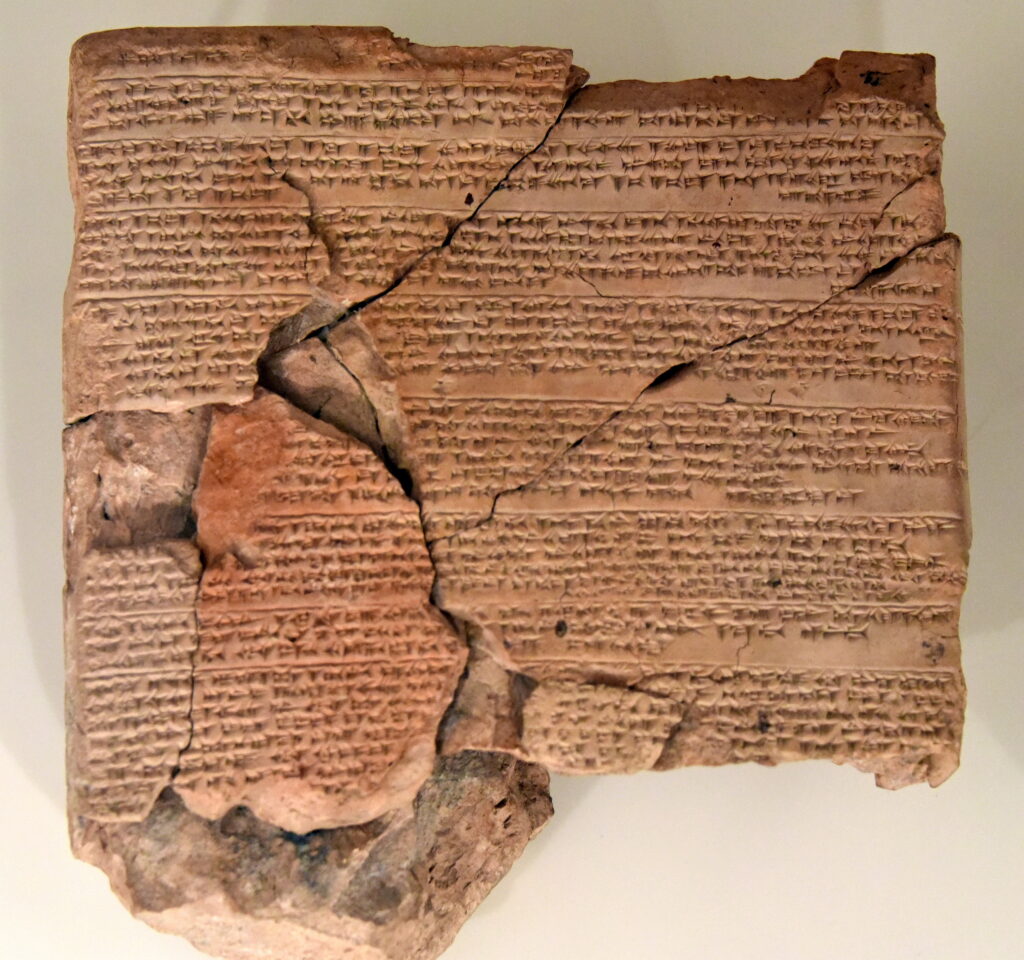

The Treaty of Kadesh

The Treaty of Kadesh – the oldest peace treaty in the world, written in cuneiform script, signed in 1274 BCE and discovered in the Hittite capital of Hattusa. The Egyptian–Hittite peace treaty, also known as the Eternal Treaty or the Silver Treaty, is the only Ancient Near Eastern treaty for which the versions of both sides have survived. It is also the earliest known surviving peace treaty. It is sometimes called the Treaty of Kadesh, after the well-documented Battle of Kadesh that had been fought some 16 years earlier, although Kadesh is not mentioned in the text. Both sides of the treaty have been the subject of intensive scholarly study. The treaty itself did not bring about a peace; in fact, “an atmosphere of enmity between Hatti and Egypt lasted many years” until the eventual treaty of alliance was signed.

The Oldest Love Poem

Prior to this time, the Bible was considered the oldest book in the world and The Song of Songs from the Bible (also known as The Song of Solomon) the oldest love poem. When it was found, the cuneiform tablet of The Love Song for Shu-Sin was taken to the Istanbul Museum in Turkey where it was stored in a drawer, untranslated and unknown, until 1951 CE when the famous Sumerologist Samuel Noah Kramer came across it while translating ancient texts. It is likely that the king, in having sexual relations with one of Inanna’s priestesses, was thought to be having sex with the goddess herself but, as Black notes, the details of the sacred marriage ritual are unknown. While the recitation of the poem by the `bride’ served a religious and social function in the community by ensuring prosperity, it is also a deeply personal and affectionate composition, spoken in the female voice, concerning romantic and erotic love. Shu-Sin reigned as king in the city of Ur from 1972-1964 BCE according to what is known in scholarly circles as the `short chronology’ but, according to the `long chronology’ used by some scholars, reigned 2037-2029 BCE. The poem, therefore, is dated according to either 1965 BCE or 2030 BCE but is most often assigned a general date of composition at around 2000 BCE. It begins with;

“Bridegroom, dear to my heart,

Goodly is your beauty, honeysweet,

Lion, dear to my heart,

Goodly is your beauty, honeysweet…”

Tiled Pavilion

The third building in the museum complex is the graceful Tiled Pavilion (Cinili Kösk), which is one of the oldest surviving Ottoman buildings in Istanbul. Built in 1472, it shows a clear Persian influence in its architecture. It was originally built for Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror as a rather grand spot for the sultan to watch games and sports. The building’s gorgeous ceramic work (mainly 16th-century Iznik tiles) and 12th- to 19th-century faience decoration have been wonderfully well-preserved.

What not to miss at the Islamic Art Museum (or Tiled Kiosk Museum)

- The stunning Tile Mihrab taken from Karamanoğlu İbrahim Bey Imaret (public kitchen) that was built in 1432.

- Sultan Murat III’s pretty Fountain of Youth dating back to 1590 and set in the wall of the final room.

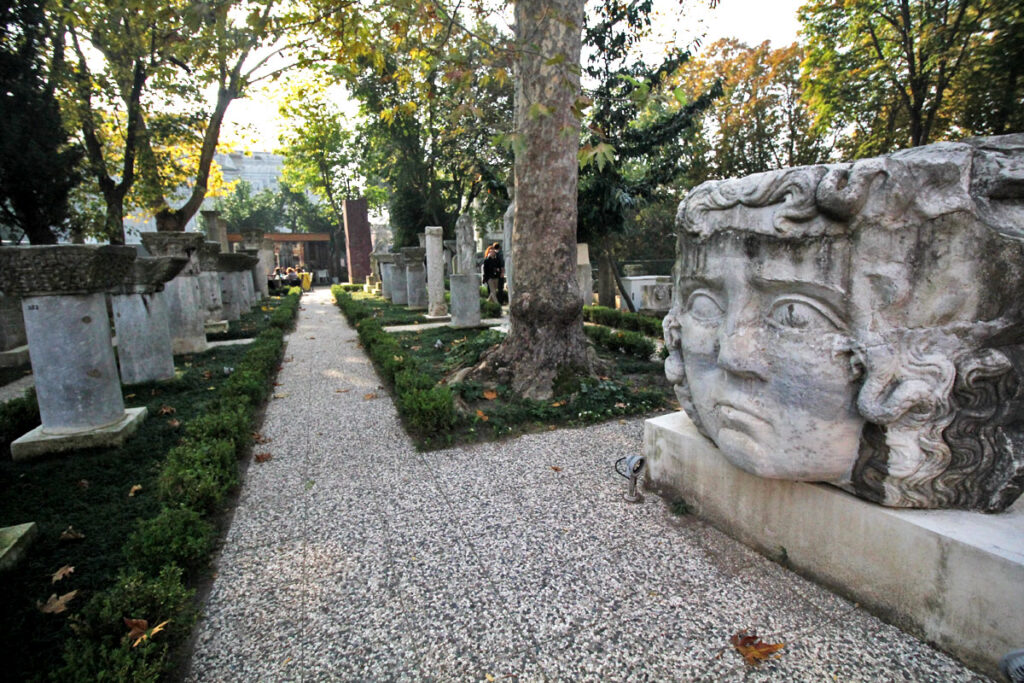

Courtyard

Outside is a tree-lined courtyard with lots of columns and statues. Recognize the Medusa head? It’s similar to the pair at the Basilica Cistern. On a nice day, this is a great place to just sit and while away the time. Depending on your level of interest, you can spend as little as an hour or the entire afternoon here. The exhibits are interesting but it can get a little tiring going through the entire complex

Virtual Tour

As the travel plans of so many of us collapsed with the spread of the coronavirus pandemic, the only possible way to visit the archaeological sites and museums is to go online and check which collections have already been digitized. In the case of Turkey, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism established Sanal Muze website that offers a 3D experience of some of the best-known state-run archaeological and ethnographic museums. The downside of this project is the fact that even though the museums offer descriptions of the exhibits, they are only available in Turkish at the moment. Click here to visit virtually Istanbul Archaeology Museums

Important Notes

If you want to see every item on display and read the excellent accompanying explanatory labels in both English and Turkish, you’ll need more than one day. So if you’re pressed for time, make sure you at least visit the breathtaking sarcophagi and Istanbul through the ages. If you have young children, also make a brief stop at their museum.