Ottoman Imperial Harem and Women Life

Introduction

Ottoman Harem – In Ottoman palaces, houses and residences, there was a private section called “Harem”. The Arabic word “haram”, pronounced in Turkish can mean “wife” among other things, and is a symbol of “sacredness” and of privacy. At the beginning of the 15th century, a number of foreign visitors to Istanbul described the many facets of the city, providing accounts of the Turks, and especially of the palaces and the harem that the Ottoman rulers called home. Every family’s harem, where its women lived and where men from outside were not permitted to go, was the very honor of that family, its sacred niche. What we know concerning life in the harem is known only indirectly. Consequently, there is no clear information in the sources about the form of life in these places, which were very private. Foreign diplomats and merchants described palace life during the 17th and 18th centuries.

Women at Seraglio Life

The harem was defined to be the women’s quarter in a Muslim household. The Imperial harem (also known as the Seraglio harem) contained the combined households of the Valide Sultan (Queen Mother), the Sultan’s favourites (hasekis), and the rest of his concubines (women whose main function was to entertain the Sultan in the bedchamber). It also contained all the Sultanas’ (daughters of the Sultan) households. Many of the harem women would never see the Sultan and became the servants necessary for the daily functioning of the harem. The reasons for harem existence can be seen from Ottoman cultural history. Ottoman tradition relied on slave concubinage along with legal marriage for reproduction. Slave concubinage was the taking of slave women for sexual reproduction. It served to emphasize the patriarchal nature of power (power being “hereditary” through sons only). Slave concubines, unlike wives, had no recognized lineage. Wives were feared to have vested interests in their own family’s affairs, which would interfere with their loyalty to their husband, hence, concubines were preferred, if one could afford them. This led to the evolution of slave concubinage as an equal form of reproduction that did not carry the risks of marriage, mainly that of the potential betrayal of a wife. The powers of the harem women were exercised through their roles within the family. Although they had no legitimate claim to power, as their favor grew with the sultan, they acquired titles such as “Sultan Kadin” which solidified their notion of political power and legitimacy within the royal family was reflected with titles including “sultan.”

During the sixteenth century, both male and female members of the imperial family used the title of “sultan”. As the role of the royal favorite concubine (title: Sultan) eroded during the seventeenth century, the title designation also changed to “kadin” or “haseki,” which were names originally reserved for less prominent members of the royal family. Henceforth, only the mother of the reigning Sultan was addressed as a Sultan: the Valide Sultan. The retention of the title of Sultan for the mother indicated the power of the Valide Sultan. After all, men could take as many concubines and odalisques as they desired, but they only had one mother. Many of the concubines and odalisques of the Imperial harem were reputed to be among the most beautiful of women in the Ottoman Empire.

Best of Turkey and Greece with 3-night cruise (With flight from USA – Small Group)

Discover your perfect Turkey vacation package using our convenient search and filter options, tailor-making a journey that captures Turkey’s unique beauty and rich heritage just for you.

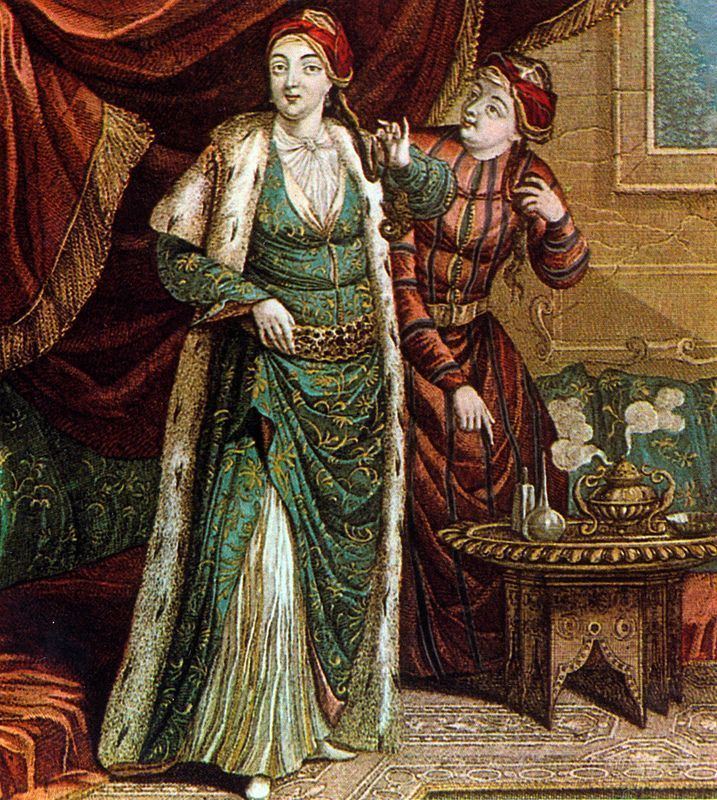

Young girls of extraordinary beauty were sent to the sultan’s court, often as gifts from the governors. Numerous harem women were Circassians, Georgians, and Abkhazians. They were usually bought from slave markets after being kidnapped or else sold by impoverished parents. Many Georgian and Circassian families encouraged their daughters to enter concubinage through slavery, as that promised to be a life of luxury and comfort. All slaves that entered the harem were termed odalisques or “women of the court” – general servants in the harem. Odalisques were not usually presented to the Sultan. Those that were of extraordinary beauty and talent, were seen as potential concubines, and trained accordingly. They learned to dance, recite poetry, play musical instruments, and master the erotic arts. Only the most gifted odalisques were presented to the Sultan as his personal gedikli (maids-in-waiting). Generally, odalisques would be assigned as servants to the oda (or court) of a harem mistress. For example, the Mistress of the Robes, or the Keeper of Baths, or the Keeper of Jewels, etc.

It was possible for these odalisques to rise through the ranks of the harem hierarchy and enjoy security through their power and position. The most powerful women in the harem were the Valide Sultan and the Kadins. The Valide Sultan was responsible for the maintenance of order and peace inside the harem. Being a female elder in the Imperial family, the Valide was expected to serve as a guide and teacher to her son by educating him about the intricacies of state politics. Often, she was asked to intervene upon the Sultan’s decisions when the Mufti (head of the Muslim religion), or the Viziers (ministers) felt that the Sultan may have made an erroneous decision. Kadin’s were the Sultan’s favourite women. Tradition allowed only four principal Kadins but unlimited number of concubines. Kadins were equivalent in rank to that of a legal wife, and were given apartments, slaves, and eunuchs. For example, during the reign of Selim II (the Sot), his favorite, the bas kadin Nurbanu had an entourage of one hundred and fifty ladies-in-waiting. The amount of properties, clothing, jewelry, and allowances given, was all-proportional to the affection the Sultan held for them.

Odalisques were at the bottom of the harem hierarchy. They were considered to be general servants in the harem. They were not usually seen to be beautiful enough to become presented to the Sultan. Odalisques that were seen as potential candidates for concubinage were trained to become talented entertainers. The greatest honour a Sultan could bestow upon a male guest was to present him with an odalisque from his court who had not yet become his concubine. These women were greatly coveted as they were beautiful and talented, and what is more important, had links into the harem hierarchy.

Concubines could be considered an equivalent to the modern version of a “one night stand”. They were odalisques that were presented to the Sultan and after that one night, they might never see the Sultan again unless the girl became pregnant with a male child. If she was successful in birthing a male child, then she would become an ikbal (favourite) to the Sultan. The female hierarchy followed the pattern of odalisques (virgins), concubines (“one night stands”), ikbals (favourites), and kadins (favourites “wives”).

Eunuchs

Harem women formed only half of the harem hierarchy. Eunuchs were the integral other half of the harem. Eunuchs were considered to be less than men and thus unable to be “tempted” by the harem women and would remain solely loyal to the Sultan. Eunuchs were castrated men and hence possessed no threat to the sanctity of the harem. According to Muslim tradition, no man could lay his eyes on another man’s harem, thus someone less than a man was required for the role of watchful guardianship over the harem women. Eunuchs tended to be male prisoners of war or slaves, castrated before puberty and condemned to a life of servitude.

White eunuchs were first provided from the conquered Christian areas of Circassia, Georgia, and Armenia. They were also culled from Hungarian, Slavonian, and German prisoners of war. These white eunuchs were captured during the conflicts that arouse between the Ottoman Empire and the Balkan countries. Black eunuchs were captured from Egypt, Abyssinia and the Sudan. Black slaves were captured from the upper Nile and transported to markets on the Mediterranean Sea – Mecca, Medina, Beirut, Izmir and Istanbul. All eunuchs were castrated enroute to the markets by Egyptian Christians or Jews, as Islam prohibited the practice of castration but not the usage of castrated slaves.

There were several different varieties of eunuchs:

Sandali, or clean-shaven: The parts are swept off by a single cut of a razor, a tube (tin or wooden) is set in the urethra, the wound is cauterized with boiling oil, and the patient is planted in a fresh dung-hill. His diet is milk, and if under puberty he often survives.

The eunuch whose penis is removed: He retains all the power of copulation and procreation without the wherewithal; and this, since the discovery of caoutchouc, has often been supplied.

The eunuch, or classical thlibias and semivir, who has been rendered sexless by the removing of the testicles…, or by their being bruised…, twisted, seared or bandaged.

Black eunuchs tended to be of the first category: Sandali, while white eunuchs were of the second or third categories, thus have part or their entire penis intact. Because of their lack of parts, black eunuchs served in the harem, while white eunuchs served in the government (and away from the women). At the height of the Ottoman Empire, as many as six to eight hundred eunuchs served within the Seraglio (palace). Most eunuchs arrived as gifts from governors of different provinces. At the end of their training as young eunuch pages, eunuchs were assigned to service. White eunuchs were placed under the patronage of various government officials or even into the service of the Sultan himself (like in Topkapi Palace). If they were black eunuchs, they were placed into the service of a harem personage, such as a Kadin, or a daughter or sister of the Sultan. They could also serve under the Kizlar Agha (master of the girls), the Chief Black Eunuch.

The Kizlar Agha was the third highest-ranking officer of the empire, after the Sultan and the Grand Vizier (Chief Minister). He was the commander of the baltaci corps (or halberdiers – part of the imperial army). His position was a pasha (general) of three tails (tails referring to peacock tails, and the most number of tails permitted being four and worn by the Sultan). He could approach the Sultan at any time, and functioned as the private messenger between the Sultan and the Grand Vizier. He was the most important link between the Sultan and the Valide Sultan (mother of the sultan).

The Kizlar Agha led the new odalisque to the Sultan’s bedchamber, and was the only “man” who could enter the harem should there have been any nocturnal emergencies. His duties were to protect the women, to provide and purchase the necessary odalisques for the harem, to oversee the promotion of the women (usually after the death of a higher-ranking kadin) and eunuchs. He acted as a witness for the Sultan’s marriage, birth ceremonies, and arranged all the royal ceremonial events, such as circumcision parties, weddings, and fêtes. He also delivered sentence to harem women accused of crimes, taking the guilty women to the executioner to be placed into sacks and drowned in the Bosphorus which lay outside the Topkapi Palace.

The Chief White Eunuch was the head of the Inner Service (which is the palace bureaucracy) and the head of the Palace School (school for white eunuchs). He was also Gatekeeper-in-Chief, head of the infirmary, and master of ceremonies of the Seraglio. The Kapi Agha controlled all messages, petitions, and State documents addressed to the Sultan, and was allowed to speak to the Sultan in person. In 1591, Murad III transferred the powers from the white to the black eunuchs as there were too many embezzlements and various other nefarious crimes being attributed to the white eunuchs, among them being purported intimacy with the harem women.

The Kapi Agha‘s loss of powers was seen through the decreasing of his ceremonial duties (which had various stipends entailed) and the decrease in his overall income. Originally, the Kapi Agha was the only eunuch allowed to speak to the Sultan alone, but as his importance decreased, the Valide Sultan and the Kizlar Agha were able to request private audience with the Sultan also. Because of their possible disloyalty, white eunuchs were assigned positions that did not bring them into contact with the harem women as many of them had incomplete castrations (still possessing of their penis). The total number of white eunuchs in the Seraglio at any given time was between 300 and 900. In the late sixteen hundreds, the power of the black eunuchs grew. During the Kadinlar Sultanati, the eunuchs increased their political leverage by taking advantage of child Sultans or mentally incompetent ones. It was during this period of enthronement of child Sultans that caused political instability. The young teenage Sultans were “guided” by regencies formed by the Valide Sultan, the Grand Vizier and the Valides other supporters. The Kizlar Agha was the Valide Sultan’s and the Kadin’s intimate and value accomplice.

Harem Populations

After the change in law regarding the Kafes and the loss of provincial governorships for the Princes. The harem population dramatically increased as the princes and their harems remained inside the Seraglio (Topkapi Palace) harem. The population further increased during the reigns of Murad III, Ahmed I, and Ibrahim, as they spent more time in the bedchamber than ever. The increase in harem women populations is also correlated by the increase in expenditures. During the reign of the Ibrahim (r. 1640-1648), the harem population experienced a minor increase while the correlated expenditures saw a whopping 28% increase from the beginning of his reign to the end of reign. This may have been due to the fact that Ibrahim was obsessed with furs and jewels. His desire to see furs everywhere in the harem greatly increased the harem expenditures as the price of furs would have gone up accordingly. This would also apply to the price of jewels too, as he sought jewels for the decoration of his beard. Although it is not recorded exactly how much the daily stipends were for all of the Sultan’s Kadins and concubines, general figures were available indicating that the Valide Sultan continued to enjoy the role as most influential and powerful member of the dynastic family by having the highest stipend. Nurbanu Sultan received a daily stipend of 2,000 aspers (currency of the time), while her successor Safiye Sultan, received 3,000 aspers after the ascension of her son Mehmed III. In contrast, the highest stipends of leading public officials were: the mufti (750 aspers per day), the chief justices of Rumeli and Anatolia (572 and 573 aspers, respectively), and the chief Janissary Agha (500 aspers). Even the Sultan himself only received a 1,000 aspers stipend.

After the Valide Sultan, the Kadins were next in the harem hierarchy to enjoy great status. Their status was even higher than the Sultana’s (Aunts and sisters of the current Sultan) as they were accorded higher stipends. The Kadin’s higher status arose from the fact that she was the mother of the potential future sultan. Murad III’s favourite Safiye kadin received stipend of 700 aspers a day, while his sisters Ismihan and Geverhan Sultans received 250 and 300 aspers a day, respectively. Murad’s aunt Mihrimah Sultan received the highest stipend (600 aspers a day) amongst all of the royal females descending from the previous Sultan. Non-haseki or non-favourite concubines tended to receive stipends that were greatly reduced from those of the haseki Kadins. This was demonstrated by the fact that at the end of Selim II’s reign, the haseki Nurbanu received 1,000 aspers a day, while Selim’s other consorts, each the mother of a son, received only 40 aspers. As the Sultans’ attention turned away from government, many of the harem women were able to manipulate the Sultan into raising their stipends in order to be able to purchase many of their jewels and furs.

By the reign of Ibrahim (r. 1640-1648), the role and stipend of the royal haseki had been diminished and instead the role and influence of the concubines had moderately increased as indicated by their stipends of 1,000 to 1,300 aspers. Other odalisques in the harem that served as general servants received stipends ranging from 13-200 aspers. Ibrahims’ penchant for women correlates with the increase in harem population. As he increased his harem size, he required more furs and jewels and thus dipped further and further into the State treasuries in order to support his extravagant tastes. His many concubines and favorites also meant that an increase in stipends was necessary, as befitted their role in his pleasures.

The general increase in harem women population also meant that the total amount of stipends required increased. The growth of the harem population follows a roughly parallel pattern with the harem expenditures. The increased spending caused a strain on the state treasury as the Sultan was spending increasing amounts of time in the harem rather than leading the Janissaries on conquest of infidel lands. Other factors that led to the diminishing of state income were the lack of campaigning or Ghazi (warfare on “infidels”- non-Muslim lands); the overall inflation of the economy, and the increase in bribery and corruption of state officials

The Pyramid within the Harem

The Harem may be seen as a pyramid at the apex of which the Valide sat in far from lonely state, since all important business passed through her hands, not least discipline without which life would have been impossible. The women could be punished and beaten if they were insolent. Should they continue to be disobedient, they were sent to the Old Saray , stripped of their savings and so left without hope of marriage or any other future. Any girl suspected of witchcraft was threatened with being flung in a sack in the Bosporus; at least, according to Ottaviano Bon, the Venetian representative in Istanbul from 1604 to 1607.

Until 582 the Harem was under the same administration of the white eunuchs which controlled the Palace School where the elite boys were trained for the chief offices of the empire. The structure of training was the same too, but not the subjects. Both had affinities with the guild system. For example, the young girls were admitted to the Harem as acemi, which was the same term as that used for the boys and meant cadet rather than recruit. Like the pages, they were kul, or members of the larger family of the sultan, rather than slaves who could be bought or sold.

The white eunuchs could propose which graduates from either school might be married to each other . The novices were registered and their training began at once. They were admitted to a dormitory with divans along the walls and there were old women in charge of groups of ten of them. Lights were left burning all night to expose lesbian advances.1s To prevent beastliness, long radishes, cucumbers and such were sent from the kitchens ready cut: so extreme was the need to prevent wanton behavior since young, lusty and lascivious girls without men could only have unchaste thoughts.

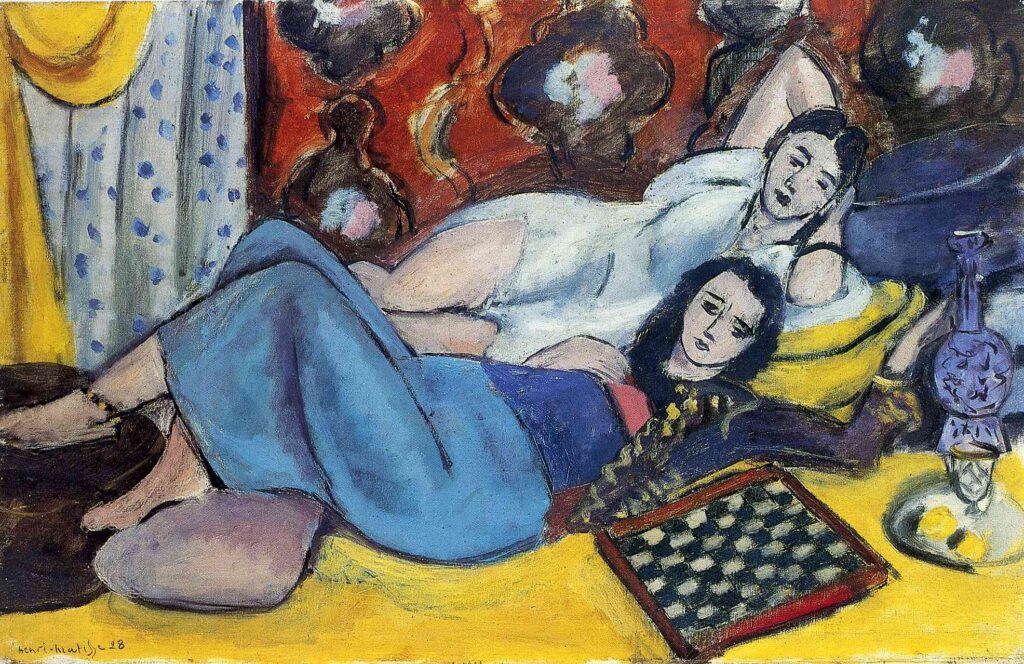

They were taught religion, and to sing and to play a musical instrument, along with dancing, poetry and the complex arts of love. If they graduated from their apprenticeship, they went on to learn to read and write and the skill of telling stories. Stories were important everywhere in the empire and nowhere more so than in a harem. Every night one of the One Thousand and One Nights was read, or so it was said. The Nights include heroes and heroines and some noble souls but, since such characters are often dull, the stories are more often about vagabonds, promiscuous women, sorceresses, criminals and unscrupulous judges, mountebanks and lying holy men. It is the world upside down, which does not mean that it was an exact mirror of the daily life of Baghdad or Istanbul.

Even at this level, failures still occurred but they could hope to be sent out into the world with some recompense, including their possible marriage to a failed student of the Palace School. The next promotion was to gedik, or the ‘privileged’, who had been seen by the sultan and who may even have had contact with him. They were not only beautiful but also intelligent and amusing besides being skilled at making love although they were still virgins. If a meteor like Hürrem entered the Harem, and the sultan was a Süleyman, the whole system broke down and the girl graduated immediately. Gediks were girls chosen by the sultan. At various periods these girls ranked as gözde, or ‘girls in the sultan’s eye’. He might select them more and more often so that they joined the elite ikbals or hassodaliks who were in sight of the top of the pyramid, since to reach it they had only to become pregnant and safely deliver a child, preferably a son. These ranks varied over the years and were not always used.

Girls who had slept with the sultan graduated to their own rooms with their own slaves and kitchen maids and their own eunuch. If a female child was born, they moved to a larger apartment and became a Hasseki Kadın, or mother of daughters. They had the right to remarry upon the death of their sultan. They were the favorites who enjoyed a handsome income compared with the pocket money that they had received before. With motherhood they had crossed the frontier and were free. If they bore a son, their ambitions were indeed achieved. At very least they were the Hasseki Sultans, or mothers of younger sons, but these royalladies were secluded and, if the boy should die, they could not marry again.

The Baş Hasseki was the mother of the eldest son and she more than anyone had to be secluded were the prince to die before her .She was the chief royal lady for so long as she lived and on her son’s accession became Valide and ruled the Harem. In theory, his death meant her seclusion and the loss of all her powers. Thus the Valide Mosque of Safiye Sultan could not be completed by her when Mehmet III died in 1603 and it was left decaying for sixty years. She was well looked after in the Old Saray but had no access to any funds except her own. There was one Valide whose personality was such that she overruled custom: Kösem. Troubles began when a girl became an ikbal because she could not help but be seen as a rival to those of the same rank and therefore be involved in the factional politics which were the zest of Harem life.

In the sixteenth century and afterwards, when the sultan selected his girl for the night, he usually came to see her or wrote to her in the morning so that she could prepare herself down to the last eyelash and the last drop of balm besides assuming clothes the like of which she could only have dreamed of wearing. The consummation of her mission took place in a special room within the Harem: never in the bedchamber of the selamlık, where pages and old women were on guard with candles all night. There was no question of the sultan conquering the ikbals; it was they who had to conquer the sultan.

Humility at the entrance to the bedchamber was something different, once between the sheets, for a woman of spirit like Hasseki Hürrem when she turned one night into thirty-eight years of love. It is untrue that girls crawled in at the foot of the bed, as if a slave deserved humiliation: this is merely western gossip. But there was humility and obedience unless teasing pleased the monarch more.

Sultanas

In 1346, the marriage between Sultan Orhan and the Byzantine princess Theodora was celebrated with incredible pomp and ceremony on the European shores of Constantinople, which did not yet belong to the Ottomans. ürhan, camped on the Asian shore, sent a fleet of thirty vessels and an escort of cavalry to retrieve his purple bride. ” At a signal, Edward Gibbon wrote in The Dedine and Fall of the Roman Empire, ”the curtains were suddenly drawn, to disclose the bride, or the victim, encircled by kneeling eunuchs and hymeneal torches; the sound of flutes and trumpets proclaimed the joyful event; and her pretended happiness was the theme of the nuptial song, which was chanted by such poets as the age could produce. Without the rites of the church, Theodora was delivered to her barbarous lord; but it had been stipulated that she could preserve her religion in the harem of Bursa.

In the early years of the Ottoman Empire, the sultans married daugh- ters of Byzantine Emperors, Anatolian princes, and Balkan Kings. These marriages were strictly diplomatic arrangements. After the conquest of Constantinople, the royal harem became populated with non- Turkish odalisques. This tradition continued until the fall of the empire. Since these slave girls were his property , in accordance with Islamic law , the sultan was not required to marry any of them. But, once in a while, a sultan-such as Süleyman the Magnificent-chose to marry a special woman.

In contrast to the odalisques, a sultan’s concubines were considered his wives, kadinlar or kadinefnediler , the number varying from four to eight. The first wife was called bash kadin (head woman), followed by ikinci kadin (second), uchuncu (third), and on down. If any one of the kadins died, the others below her moved up a rank, but not before the chief black eunuch delivered the sultan’s approval for such a promotion.

It is a common fantasy to imagine sultans actually having sexual relations with hundreds of women in their harem. In some cases, this might have been true. For example, when Murad III died, over a hundred cradles were being rocked. But several sultans chose to take only one kadin Selim 1, Mehmed III, Murad IV, Ahmed II and as far as we can conjecture, they remained faithful to these women. Most sultans spent nights with different of their favored women in tum, and to prevent disputes among them, they kept a schedule. The haznedar (the chief treasurer) recorded each ”couching” in a special diary in order to establish the birth and legitimacy of the children. This extraordinary chronicle, which survives today , discloses not only sexual intimacies but also such historical events as the execution of Gülfem Kadin, one of Süleyman ‘s wives, for selling her ”couching” turn to another woman. Much to the chagrin of Western minds, there seem to have been no outright orgies involving the sultan and his many women. It is not diffıcult to assume, however , that some of the more debauched and insane rulers, like Ibrahİm, did indulge in less routine sexual rituals

A sultan’s failure to favor each wife with equal enthusiasm stirred up a great deal of anxiety , insecurity and malevolence. Mahidevran Sultana, for example, mutilated Roxalena’s face, Gülrish Sultana rushed the odalisque Gülbeyaz off a cliff, Hürrem Sultana was strangled, Bezmialem Sultana mysteriously vanished. Each glass of sherbet potentially contained poison. There were alliances, cliques, and a perpetual silent war. This ambience affected not only the emotional climate of the harem but also state politics. ”The rigorous discipline, which turns the harem in a prison, is justifıed by the passionate disposition of these women, which may impel them to who knows what aberrations,, commented historian Alain Grosrichard in Structure du serail(1979).

Harem Women and Politics

The excessive interference of the harem women in state politics was instru- mental in the decline and fall of the empire. Ironically , such meddling began during the reign of Suleyman the Magnifıcent, the most powerful period in the empire’s history (l520-66). It was then that the women moved with Roxalena from the Old Palace, built by Mehmed the Conqueror, to the Seraglio harem ( 1541 ) , and approached the seat of power .This marked the beginning of the Sultanate, of the Reign of Women, which lasted a century and a half, until the end of the struggle between Kösem and Turhan sultanas (1687).

After Suleyman’s death, the sultans no longer led their armies in campaign or in battle, retiring instead to the womb of the harem. They detached themselves from world affairs and spent most of their time in the company of women. This royal seclusion greatly diminished their ability to govern, and in varying degrees, sultanas began wielding influence over state officials, with bribery and patronage supplanting promotion on the basis of merit. A succession of child sultans and mentally deranged ones after Mehmed III’s death in 1603 made women the power behind the throne.

A great deal of mystery surrounds the woman who sleeps next to Mehmed the Conqueror in a nameless coffin. The mullahs (Moslem theologians) claim it is lrene, Iater declared an Orthodox saint, with whom the sultan had become obsessed: ”He not only consumed days and nights with her but boomed with continual jealousy, according to William Pointer’s 1566 allegory Palace of Pleasure. He offered her everything, but Irene would not abjure her faith. The mullahs reproached the sultan for courting a gavur (infidel). According to Richard Davey’s Sultan and His Subjects (1897), one day Mehmed gathered all the mullahs in the courtyard of his palace. Irene stood in the center , concealed under a glittering veil, which the Sultan slowly lifted, revealing her exquisite beauty .”You see, she is more beautiful than any woman you have ever seen, he said, ”lovelier than the hurries of your dreams. And I love her more than I do my own life. But my life is worthless compared to my love for Islam.” He seized and twisted the long, golden tresses of Irene and, with one stroke of his scimitar, severed her head from her body.

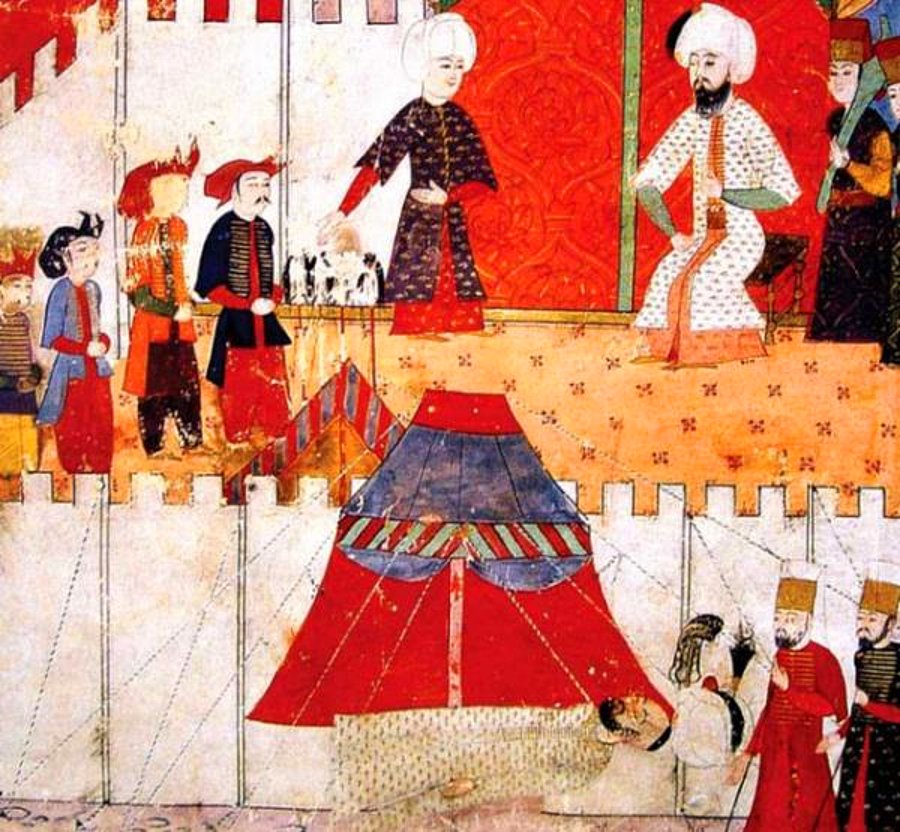

Suleiman the Magnificent ordered the execution of his kadin Gülfem when she failed one night to appear in his bed. During one of his debauches, the mad Sultan Ibrahim ordered al1 his women seized during the night, stuffed in sacks, and thrown into the Bosphorus. One was saved by French sailors and taken to Paris, where she must have had some stories to tell.

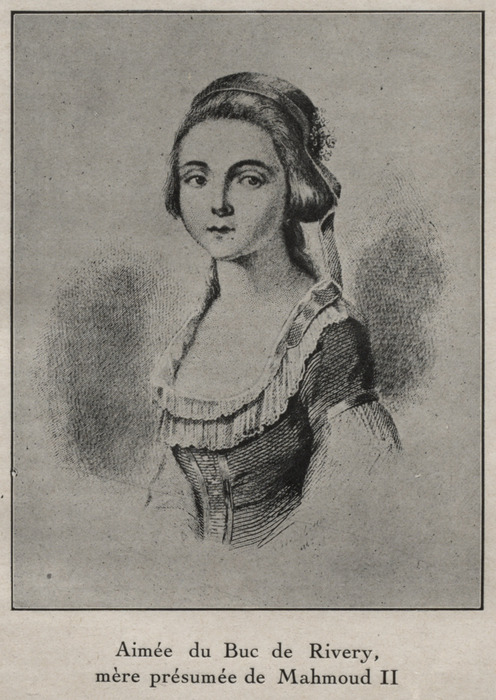

Among the many powerful and interesting sultanas who lived, loved, and ruled in the Seraglio, three deserve special attention. Each embodies the nuances of the century in which she lived. Roxalena (1526- 58) was the fırst woman legal1y to marry a sultan, move into the Seraglio with her entourage, and gain complete ascendancy over the greatest of the sultans, Süleyman the Magnifıcent. Kösem Sultana reigned the longest and saw the most. And Nakshedil Sultana -Aimee de Rivery-lived the sort of life legends are made of.

Major Ottoman Sultanas

Roxalena (Hürrem Sultana)

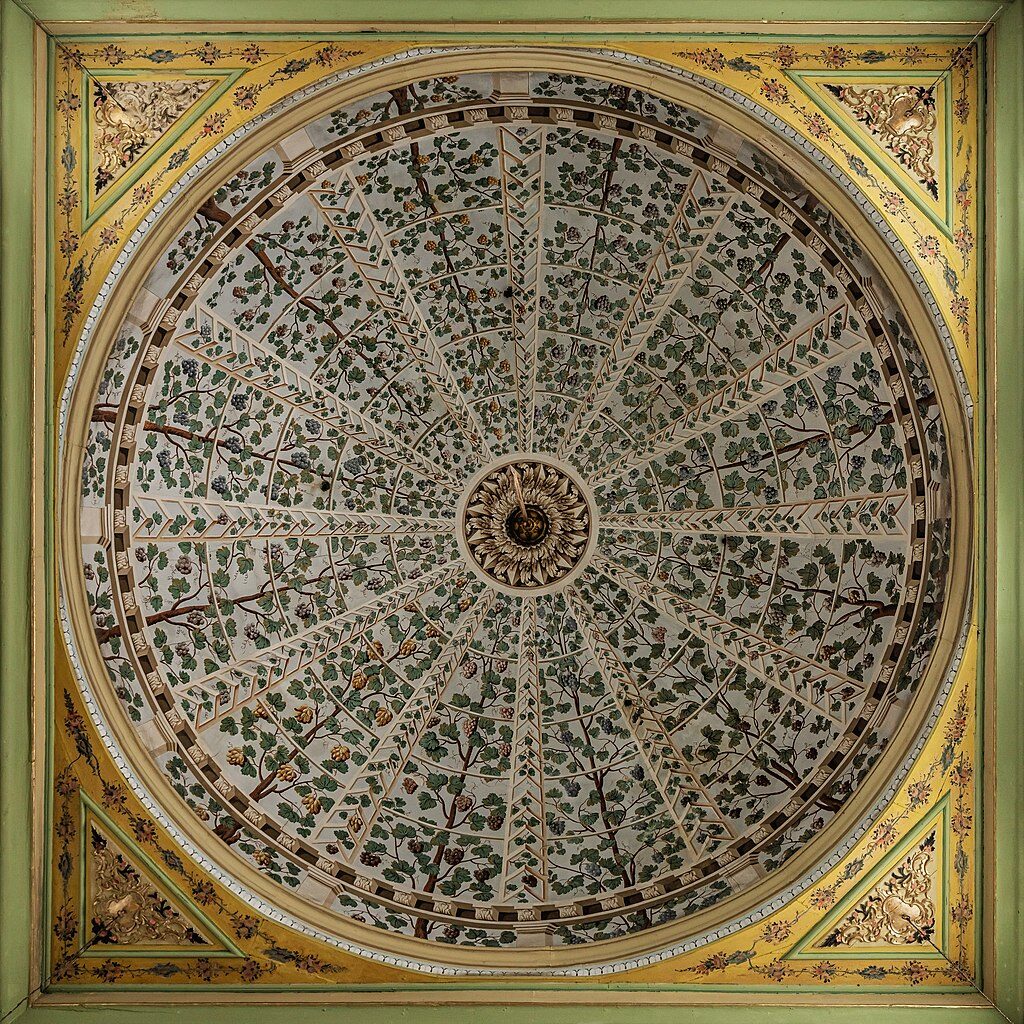

On the third of Istanbul’s seven hills rises the Mosque of Suleiman the Magnificent, the most glorious silhouette above the promontory .It is colossal and imposing, but it also has a capricious charm, reflecting the genius and exuberant spirit of its architect, Sinan. Numerous smaller domes are scattered whimsically around the central dome, like soap bubbles. Four stiletto minarets soar above the skyline. Inside, the mosque is dark and somber, despite the beautiful windows of jeweled Persian glass and colorful tiles around the mihrab (niche indicating Mecca). Its quiet dimness, its silence and desertion make it seem peaceful, almost ethereal, as is the garden in back, which shelters the mausoleums of Süleyman and his legendary wife Roxalena. A grapevine straggles over the walls of their tombs, and a profusion of blood-red amaranthus, the flower known as ”love lies bleeding, sprouts out of the earth.

The lovers slumber in their graves, once the most powerful mortals of this city, now sacks of bones. it makes one think of lstanbul’s contradictions: the Bosphorus separating two continents, unable to make up its mind where its a1legiance lies, caught between wealth and starvation, between the physical and the spiritual, the sacred and profane. The prayer chant from the minaret wafts like smoke over the rooftops of the city , just as it must have done when Roxalena was alive. Her portraits suggest a mosaic refinement, with classical features and blazing red hair. There is depth and inte1ligence in her eyes. An extraordinary strategist and a true political artist, Roxalena planned her moves as if she were playing chess.

At the beginning, Suleiman was attracted to her silent charm, and she became his favorite. Soon she bore him a son, which elevated her to third kadin the third most powerful woman in the hierarchy of the harem. Roxalena was aware that, according to the Code of Laws established by Mehmed the Conqueror, the throne passed to the oldest male, obliging him to get rid of a1l his brothers in order to secure it for his own offspring. As such, from the beginning, Prince Mustafa, the heir apparent, was the death warrant of her own male children. Roxalena was so full of light that Suleiman seemed blind to her dark side. He named her Hürrem, ”the laughing one,” because ofher crystalline laughter and freedom from inhibition. Yet Hürrem was secretly tormented. In 154l, when the Old Palace, which housed the sultan’s harem, partially burned down, Roxalena, with her entourage of odalisques and eunuchs, moved to the Grand Seraglio, where she could be closer to Suleiman and the seat of power, a move that marked the beginning of the Grand Harem and ”The Reign of Women.”

With Mustafa and Gülbahar tucked far away , Roxalena had still another antagonist to deal with, the man who had originally owned her, the inseparable friend and companion of Süleyman, Ibrahim, who shared Süleyman’s tent and his dreams, who had been promoted from the status of royal falconer to Lord of Rumelia and, later , grand vizier .Ibrahim had been chosen to marry the sultan’s own sister, Hatice Sultana, and had been the object of endless wealth and honor. He may have presented Roxalena to Suleiman as a move to consolidate his power; if so, the scheme backfired. Grown resentful of his influence and jealous of Suleiman’s affection for him, Roxalena set out to orchestrate his death. She took advantage of every bit of gossip and information to inflame Suleiman’s mind against his friend. One night, when Ibrahim was in the Seraglio as a privileged friend of the sultan, the deaf-mute guards strangled him in his sleep. Roxalena may have been responsible for Ibrahim’s assassination, and there are many who have accused her of it, but there is no conclusive evidence.

Some time after this, Suleiman declared to Roxalena that he wanted to build her a new palace. She feared that putting her out of sight might mean putting her out of mind and, eventually, out of favor. To distract Suleiman, she came up with a more challenging project: a mosque to be built by the greatest architect of the time, Sinan, and to be named after the sultan himsel the Süleymaniye, the Mosque of Suleiman the Magnifıcent. Once again she triumphed. The year was l 549.

As Roxalena’s sons grew older, Prince Mustafa loomed as a greater and greater obstacle. He was an able and intelligent prince, much admired by the people and the army. He was also Suleiman’s favorite son. How to cause his fall from grace? A forged letter supposedly written by Mustafa to the shah of Persia, declaring that he wanted to dethrone his father and asking for the shah’s assistance, turned father against son and provoked battle on the plains of Ereğli. Mustafa ran to his father , alone, unarmed, to redeem himself. He reached the sultan’s tent, going through four partitions. When he came to the fıfth, his cries echoed through the plains. It is said that Suleiman shed tears for the son he had ki11ed, and for the father who could kill such a son. Of Roxalena ‘s four sons, Mehmed died young of natural causes; Cihangir , possessed of a brilliant mind, was deformed and epileptic; Beyazit was able but cruel. Selim was her choice as heir, because she was convinced that his soft nature would not allow him to murder his brothers. She also knew that Selim drank to dull his prophetic awareness of impending death. Risking Suleiman’s wrath, she was not reluctant to supply the wine to ease her son’s pain. He became known as Selim the Sot.

But no matter how much Roxalena plotted, she could not alter kismet. She did not live to realize her dream of becoming the valide sultana. Nor did she live to see the twist of fate that set brother against brother , father against son. She would not see the struggle for the throne between Selim and Beyazit, which drove Beyazit to take refuge with the shah of Persia. She would not see how Suleiman forced the shah to extradite Beyazit, and how he promptly assassinated him, as well as the shah and his sons. Roxalena died in 1558. Her place was occupied by her daughter Mihrimah and her granddaughter Aysha Humashah. Selim the Sot and his son Murad III both preferred women and pleasure to political matters. Their sisters, wives, and daughters took full advantage of the weak nature of the pair, dabbling in politics and securing important posts for their own husbands and sons. It was Mihrimah, rather than his sons, that Suleiman consulted on important issues. Roxalena had trained her daughter well.

Kösem Sultana

Princes Ahmed and Mustafa lived together in the Golden Cage. When Ahmed became sultan, he did not have the heart to murder his brother, but he did keep Mustafa in the Cage-with just a few women. He built a wall to block the entrance, leaving a small window through which food was passed to Mustafa, as well as alcohol and opium. Fourteen years later , this same wall was hammered down, and the utterly demented Mustafa was declared sultan. His own years of isolation had created in Ahmed a void that çon(umed continual diversion. He took a different woman to bed each night, but he favored the Greek beauty Kösem, lavishing on her the finest jewels from his hoard. Kösem was fifteen years old when she became the favorite of fifteen- year-old Ahmed 1.

Ahmed ruled from 1603 to 1617, leaving Kösem a young widow. Mustafa was released from the Cage, to become sultan, while Kösem ‘s own sons, Murad, Beyazit, and Ibrahim, took his place there. After only a few months, the crazed Mustafa was dethroned by the eunuch corps, who did not favor him, and retumed to the Cage. Mustafa’s son Osman succeded him, but the young sultan fell victim to the uprising of the janissaries and the sipahis (cavalry). Troops marched into the Seraglio and dragged the sultan to the common Yedikule (Seven Towers) prison. He was murdered, his ear cut off and presented to his mother as an affront. Although fratricide was common in the Ottoman Empire, this was the first act of regicide. Once again, mad Mustafa was dragged out of the Cage (1622) and enthroned. This time he ordered the execution of Kösem’s sons. The eunuch corps-again-intervened and crowned Kösem’s oldest son as Murad IV (1623-40). Thus Kösem attained her ambition of becoming Valide Sultana. But Murad’s cruelty disturbed her. He passed a law prohibiting drinking and smoking throughout the empire, while he himself abused both habits. He ordered the execution of anyone else breaking this law .In a drunken stupor and accompanied by a mysterious dervish, Murad wandered the streets incognito, searching for victims. Corpses hung at every street corner. Kösem’s youngest son, Ibrahim, was also deranged.

She set her hopes on handsome, astute, and brave Beyazit, who was highly skilled injousting. One day, Beyazit threw Murad off in a joust. Shortly thereafter, while campaigning in Persia, Beyazit was killed by order of his brother, an incident that later inspired Racine’s tragedy Bejazit.It was debauchery that brought about Murad’s demise. On his death- bed, he told his mother how much he disdained his brother Ibrahim, and how it would be better for the dynasty to end rather than continue with insane royal seed. He ordered Ibrahim’s death, but Kösem intervened, and Ibrahim was ordered out of the Cage. He was too terrified to come out, convinced that his cruel brother was playing a trick to torment him. He refused to leave until Murad’s corpse had been brought before him, and even then Kösem had to coax him out as if cajoling a frightened kitten with food. It was Ibrahim’s reign (1640-48) that marked Kösem’s real power as valide. With the help of the grand vizier, Mustafa Pasha, the empire was hers to rule. Feeble Ibrahim, entirely absorbed in the joys of the harem, was being devoured by lust and debauchery. The French called him ”Le Fou de’ Fourrures” because of his obsession with furs; he wanted to touch, feel, and see furs everywhere in the harem. He searched the empire for its fattest woman. She was an Armenian, with whom he became madly infatuated, declaring her the Governor General of Damascus. Favored ladies were al- lowed to take what they pleased from the bazaars. He made his sisters serve the odalisques and presented his odalisques with the wealthiest imperial estates. In a night of madness, he had his entire harem put in sacks and drowned. It would have been better for the empire if Ibrahim had remained childless. But Kösem was determined to hold power as long as possible. She employed a man named Cinci Hoca (Keeper of the Djinns) to concoct various herbs of fertility .Perhaps they were all too effective; Ibrahim had six sons, one after another.

Tales of Ibrahini’s madness spread over the empire, finally provoking the janissaries to mutiny; they marched to the Gates of Felicity and demanded the sultan’s head. Kösem pleaded with them for several hours. She surrendered when they promised not to kill him but instead to put him back in the Cage. Confıned once again, Ibrahim became a raving lunatic. His cries pierced through the thick walls day and night. Ten days after his incarceration, he was strangled by order of the Mufti (the head imam, or Moslem priest). Ibrahim’s seven-year~old son, Mehmed, by Turhan Sultana, became the new sultan. Kösem had no intention of relinquishing the offıce of valide to Turhan, and she refused to move to the House of Tears. She schemed to have Mehmed poisoned, so that she could elevate to the throne a young orphan prince whom she could manipulate. A war of two sultanas began. The year was 1651. The janissaries supported Kösem, but the new grand vizier, Köprülü Mehmed Pasha, and the rest of the palace administration favored Turhan.

Kösem conspired to admit the janissaries into the harem one night to dis- patch the young sultan and his mother .But Turhan had been informed about this conspiracy . Kösem found herself facing the eunuch corps instead, supporters of Turhan, who demanded her life. She went mad, stuffıng her precious jewels into her pockets and fleeing through the intricate mazes of the harem, which she knew better than any- one. She crept into a small cabinet, hoping that the eunuchs would go past her and the janissaries come to the rescue. But a piece of her skirt caught in the door, betraying her hiding place. The eunuchs dragged her out, tearing her clothes, stealing her jewels. She fought; but she was an old woman now . One of her attackers strangled her with a curtain. Her naked, bleeding body was dragged outside and flaunted before the janissaries. Kösem had enjoyed the longest reign of any of the harem women, almost half a century .But she died in horror and abject loneliness. Turhan triumphed. Her son a child, she assumed absolute power. While she was well liked in the harem, Turhan was a simple woman, unsophisticated in state affairs. With her death in ı687, the Reign of Women came to an end.

Aimée du Buc de Rivéry (Nakş-î-Dil Valide Sultana)

No sultana is more intriguing than Nakshedil(Nakş-î-Dil). Her life is shrouded in such mystery that, to this day, no one is sure whether Nakshedil and Aimee de Rivery, the fair, blue-eyed girl from Martinique, were indeed one and the same. During the reign of Sultan Abdulaziz, some time in the middle of the last century , the French Empress Eugenie came to Istanbul. The empress wanted to visit the women in the sultan’s harem; this was arranged, and the ladies met. They fascinated one another , but could not converse. ”Is there any among you who speaks French?” the empress managed to convey. They all looked at each other, whispered, and shook their heads. ”Then,” my grandmother continued, ”an old woman spoke up: ‘Before Nakshedil Sultana died, there was a young girl she liked. She named her Naime because it sounded,’ she said, ‘like her own name before she was brought. She taught this girl, herself the language of the French. And 1 think the girl still lives in the Old Palace”

Immediately Naime was delivered from the darkness of the Palace of the Unwanted Ones and brought to the empress. She was a shy little girl, but she indeed spoke fluent French, with a Martinique accent. When the sultan saw how much Empress Eugenie liked this forgotten girl, he offered Naime to her as a present to take back with her to France. However, a young man in Eugenie’s entourage fel1 in love with Naime and fınally asked the empress for Naime’s hand in marriage. At this, the sultan intervened, saying the girl was a Moslem and the only way a gavur (infidel) could marry her was by converting to Islam. Though he was from a devout Catholic family , the young man did not hesitate to change his faith. As a Moslem, he was given a ward in Macedonia, a town called Prilep, near Skopje. The couple moved there, had many children, and started fırst a vineyard, which was a failure, then a successful gunpowder business, the name of which became our family’s, Barutçu (gunpowder makers).

We do know that Aimet’ DeBucq de Rivery was born in 1763 to a noble family in Martinique. Her cousin ]osephine Tascher de la Pagerie married Napoleon Bonaparte. A legend tells of the two young girls going to a Creole fortunetel in Pointe Royale, who predicted that they would both grow up to be queens, one to rule the East, the other the W est. In 1784, on her retum to Martinique, after attending convent school in Nantes, Aimee was kidnapped by Barbarossa’s corsairs. Twenty-one years old, Aimee was sold to the Dey of Algiers. Captivated by her beauty , the dey saw an opportunity to win the sultan’s favor. He presented the girl to Abdulhamid I.

(Embroidered on the Heart) and made her his favorite. She rose to the status of fourth kadin and found herself in the political crossfire of the harem: the first kadİn, Nükhet Seza, and the second kadin, Mihrimah, were each trying to put their sons on the throne. Nakshedil observed, and she leamed. In 1789, the year of the French Revolution, Abdulhamid died. At the age of twenty-seven, Selim III became sultan. He asked Nakshedil to remaİn at the Seraglio harem with her son, Mahmud his nephew. For Selim, Nakshedil was a personification of the France he had always admired. She became his confidante. She taught him French; and for the first time, a permanent ambassador was sent from Istanbul to Paris. Selim started a French newspaper and let Nakshedil decorate the palace in rococo style.

These Francophile reforms cost him his life. Selim was assassinated in 1807 by religious fanatics who disapproved of his liberalism. The assassins also sought to kill Mahmud, but Nakshedil saved her son by concealing him inside a fumace. Thus Mahmud became the next Sultan, accomplishing significant reforms in the empire that are, for the most part, attributed to the intiuence of his mother. Although Aimee accepted Islam as part of the harem etiquette, she always remained a Christian in her heart. Her last wish was for a priest to perform the last rites. Her son did not deny her this: as Aimee lay dying, a Catholic priest passed-for the first time-through the Gates of Felicity and into the harem.