A General Look at Turkish Arts

Turkish Arts has many facets including metal, glass, wood, and leather artwork as well as handwritten books, lamps, and stone carvings. However, the traditional art of miniatures, marbling, and calligraphy are some of the most well-known. We went back in time to follow the story of these unique visual forms of Turkish art.

Traditional Turkish Art

Turkish Calligraphy

Best of Turkey and Greece with 3-night cruise (With flight from USA – Small Group)

Although calligraphy is not Turkish in its origins, the Ottoman’s adopted the unique art form and carried it to its artistic height over a 500-year period. Islamic calligraphy, specifically, includes Arabic, Ottoman, and Persian calligraphy and its development is tied closely to excerpts from the Qur’an as one of the main artistic expressions of Islamic cultures. In the Ottoman tradition, Diwani (a cursive style of Arabic calligraphy) was developed in the 16th-century, reaching its pinnacle during the reign of Suleyman the Magnificent. Such mundane items as tax reports, property deeds and imperial edicts became exquisite works of art. This aptly reflects the bureaucratic nature of the empire, with its stress on writing and registering. Turkish calligraphers contributed to the development of new and more ornate styles of calligraphy. Each of the sultans had their own monogram in stylized script, called a Tugra. Sultan Ahmet III and Sultan Bayezit II were skilled calligraphers. In 1928 Ataturk introduced the Latin alphabet, sounding the death knell of the art of Arabic calligraphy in Turkey. Many of the greatest works were preserved in the extensive Ottoman archives and can be seen at Topkapi Palace and Ibrahim Pasha Museum (Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts). Turkish calligraphists were known to always make their own tools, including paper painted with natural dyes, pens made of hard reeds, and ink which was composed of burned pine and linseed oil.

Paper Marbling

Marbled paper or “Ebru” is an art form that was developed in Central Asia and Ottoman Empire in the fifteenth century. Traditionally, this paper was used for borders on Ottoman panels and miniatures, and for the inside covers and flyleaves of books. In the 17th century European travelers collected examples of these papers and thus the Ebru art was introduced to Europe, where it became very popular too.

In order to perform the Ebru art a shallow tray is filled with water and some viscous material such as gum and the gall fluid of cattle. This viscous liquid makes the colors floating on the water. Various mineral and vegetable dyes are sprinkled and carefully applied to the surface of the water with a small brush. Depending on the creativity of the artist, drops of negative colors are put on floating colors; or the already existing and floating dyes in the water are gently manipulated with a thin brush or by blowing on them directly or through a straw. The process is repeated until the surface of the water is covered with unique and unrepeatable patterns, flower designs, circles, etc. A blank sheet of paper is laid on the water for few minutes so the floating colors are transferred to the paper. Than the paper is carefully removed from the tray and naturally dried.

Today mass-produced marbled paper is used for many decorational purposes, though the art of marbling continues. It’s a very popular art in Turkey, there are many artists and art houses still producing traditional Ebru, especially in Istanbul. In 2014 Ebru art was inscribed in the UNESCO’s List of Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Metal Artwork

Turkish metal artwork dates as early as the 2nd and 3rd century BC in central Asia. In Anatolia, the oldest existing Seljuk piece of metalwork is a silver tray with the inscription “Alp Arslan is the Greatest Sultan” and a silver candle stick dated 1137. Both pieces are at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Metal artwork reached its pinnacle in the Ottoman Empire with the making of weaponry, such as swords, helmets, armor, dagger and knives. For domestic ware, copper or copper/zinc (tombac)was the material of choice although bronze, silver and gold were also used. A mass of copper would be beaten with a hammer (dogme) and turned into a slab, which would then be shaped by an artisan to the desired form.

The choicest specimens of Seljuk and Ottoman metalwork can be seen at the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art. Like the other branches of art, the Ottoman art of metal at the outset took over the Seljuk cultural heritage, with the result that it became a melting pot for a variety of trends as befits an empire that combined many lands and peoples. The widespread implementation in the 14th century of the art of repoussé, familiar to us from Seljuk metalwork, is one of the outstanding features of the period

Turkish Felt Making

Felt making is one of the oldest crafts which dates back to 5th or 4th century BC, it’s maybe the oldest textile known to man. Felt has been used in ancient times especially in Central Asia where the Turks are originated, to make carpets, tents, shoes, hats, saddle bags, shepherd’s’ cloak against cold weather, and so on. There are proofs that Uighurs in Central Asia and the Hittites in Anatolia used felt in their daily life.

There is no sewing or weaving in this process; wool fibers are felted using moisture, friction and heat. When the wool shrinks, the fibres interlock and mat together to make an impenetrable fabric. The normal treatment is either by wet-felting the fibers or dry-felting using special needles. The wool used for felting can be of lamb, sheep, cashmere, angora, and alpaca.

Felt, known as Keçe in Turkish, is produced in many places around the world and of course in Turkey too. For many years during our modern ages the felt business has lost its popularity when textile machines, new textile products, and machine-made rugs have become popular. But lately the young generation, influenced by felt-masters such as Mr. Arif Con in Tire – Izmir and Mr. Mehmet Girgic in Konya, are trying to turn this business alive once again. There are also few felt masters in Afyon, Balikesir, Sanliurfa, Erzurum and Kars provinces. The felt-making remains as an important Turkish art since Turks were in Central Asia.

Today felt makers produce so many variety of goods; shoes, hats, jewelry and accessories, bags, slippers, door mats, decorative objects, felt mural and pictures and many other colorful and fashionable items. They can also combine felt with leather, silk, lace and copper.

Kat’i Art

Kat’i is the art of stenciling intricate designs into leather or paper. The paper could be a simple one or an Ebru (marbling art) paper. A “nevregen”, a small sharp knife was used to carve into the paper and the leather. The process of pasting was done with a mixture called “cirisli muhallebi” in Turkish. This was a mixture of milk, rice flour and book binder’s paste. The surface on which the cut-outs were pasted was called “male”. Those surfaces on which the cut-outs were directly carved were called “female”. Besides simple shapes, complex paper cuts were produced that showed colorful flowers, flower gardens or a landscape, calligraphic decorations and so on, giving way to three-dimensional images.

The origins of this art can be traced back to Iran. In the 15th century delicate and beautifully composed patterns in leather filigree and paper cut-out were practiced with great skills and patience. Ottoman artists, called as “Kati’an”, have started used it from 16th century on in order to decorate the bindings of religious and philosophical texts. This art became very popular especially during the times of Suleyman the Magnificent. Kat’i was introduced to Europe around 17th century when western travelers took some examples with them on their journey back home. Unfortunately today there are very few Kat’i masters left; it’s an art form which is dying.

Turkish Glass Art

Glass was an advanced art among the Turks in Central Asia. They transported their own skill and taste wherever they conquered and settled and added it to local art, raising it to to new highs. The Seljuks were well known for their raised glass called semsiye. They used both blown and wheel-turned glass techniques and decorated them with incised motifs (oyma), engraving (kesme) and lustre (perdahlama).

The Ottomans improved upon the art by innovating new techniques. Glassworkers were organized into a powerful guild, protected by the government and they participated in royal ceremonies as shown in the miniatures .

Mother of Pearl Art

Sedef is the Turkish name of mother of pearl and is widely used in traditional arts as inlay. Especially during the Ottoman period it became very popular and many inlay objects and furniture was made between 15th and 19th centuries. The mother of pearl is obtained from the interior of the pearl oyster shell which was usually imported from Asia, than local artists worked it on the wood making remarkable chairs, tables, boxes, chest of drawers, mirror frames, and so on. This type of art was widespread in all Anatolia and the Middle East.

The quality of the mother of pearl is very important. All shelled mollusks possess a shell with a sort of mother of pearl, but the freshwater mollusks are one of the best because they provide large flat pearl blanks and are milk white to create a nice contrast on dark wood, thus these are the preferred ones. It’s not easy to convert an arched shell to flat pieces for inlay blanks, but it’s the craftmen’s skill. Also the wood has to be good quality, usually walnut, mahogany or rose wood is selected.

In the Sedef inlay technique, the craftsman (Sedefkar in Turkish) first draws his design on the wood cutting out the lines, then inserts the brass or silver wire in these lines with the help of a small hammer; this is called “tel çekme” or “telkari” technique. Then he slightly cuts out the areas between these wires in order to place the mother of pearl blanks that are cut according to the shape of the design. The craftsman glues them in their spot than waits for a couple of days to dry before sandpapering and waxing. Besides the mother of pearl, also tortoise shell, camel bones and ivory can be mixed to decorate the design of Sedef furniture. Usually floral designs are used.

Today, there are few artists left in this business. Especially Gaziantep is one of the cities where one can still experience hand made art of the mother of pearl inlay tradition.

The Art of Turkish Jewelry

Turkish jewelry had to be ornate and extremely colorful. Jewelers used a variety of metals in order to fashion a piece of jewelry, which is the main difference from European jewelry where the same metal is repeated. Another feature of Turkish jewelry is that instead of strict symmetry, the nature of the stone and metal are given prominence. For instance, the natural characteristics of a ruby and emerald reflect the Ottoman feature of jewelry. Jewelry was produced in the palace or in workshops elsewhere. Ottoman jewelry was designed using natural motifs which reflected the prevailing tastes. As the types of stones and the mines increased during the expansion of the Empire, jewelry production increased also. From the 18th century onwards, Western trends led to an exaggerated increase in the size of jewelry. Jewelled golden, silver, crystal, mother-of-pearl or ivory belts were the essential accessories of the Ottoman woman. Belt buckles with floral or geometric motifs decorated with diamonds, rubies, turquoise, and emeralds were sometimes worn at the waist and other times over the hips

Meerschaum Stone Carving

The major local art in Eskisehir is Meerschaum or Lületasi, called as “white gold” or “aktas” or “patal” by locals. Working with meerschaum is a handicraft and special to this province.

Meerschaum may have white, yellowish, gray or reddish and mat colors. Its hardness degree is between 2-2.5, and it is lightly adhesive and porous. It is extracted from 20-130 meters (65-426 feet) depth of the ground as big and small rounds. Small rounds are collected by digging deep wells and tunnels connected to these wells. When first extracted from the ground, the stone is soft, but it hardens on exposure to heat or when dried.

Some wells are watery, some wells are dry. Stones of watery wells are much better. Meerschaum is produced in different places like Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Utah, Mexico, Madrid, and Nairobi; however, they are unimportant in quantity and low in quality. Meerschaum with the highest quality is found in Eskisehir province. The property that while drying it keeps the remains of moisture and gases in its body, makes Meerschaum a suitable material for making tobacco pipes as well as a good filling material for absorbent, filter or isolation in industry. It became an indispensable material in industry for years. It is used in making cigarette-holder, tobacco pipe and decorative goods and in automobile paint industry. It is added to porcelain paste, insecticides, powder and stain removing medicines.

There are three geological periods in its formation:

- First Order : It is an ore in sandy-clay soil at 10-14 meters depth.

- Second Order : It forms between 40-60 meters depth. It is an ore existing in clay.

- Third Order : Meerschaum with the highest quality forms in Conglomerate series and it exists in 80-130 meters depth fitting with the topography. Other kinds of meerschaum are: cotton-piece, granular cast, unit unity and puny.

Export of Meerschaum has started around 1970’s. In addition to tobacco pipes, products like chess sets, bracelets, necklaces and earrings have an important ratio in export. Foreign customers are mostly from USA, Austria, Holland, Belgium and Germany. Another value to Turkish economy is added by selling handworks made by Meerschaum to tourists visiting Turkey.The places nearby Eskisehir where Meerschaum extracted from are: Sarisu, Yenisehir, Türkmentokat, Gökçeoglu, Karaçay, Sögütçük, Sepetçi, Margi, Nemli, Kümbet, Yeniköy, Kepertepe, Karahöyük and Basören.

Stone Carving

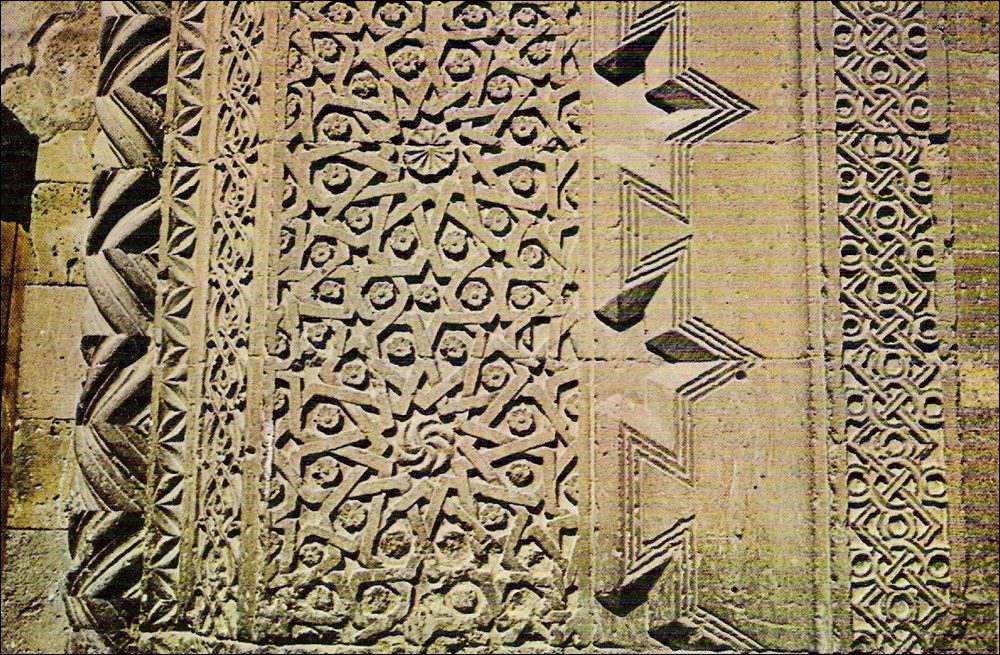

Stone and wood were the main construction material in Anatolian Turkish culture. Carved decorations in the form of figurative and ornamental compositions appeared on mosques, madrasahs, turbes, tombstones, and caravanserais. By the thirteen century designs moved towards more complex and intricate decorations and embroidery-like low reliefs with dense geometrical interlace angular motifs, Kufi inscriptions. In the Ottoman period emphasis shifted to plainer decorations and more imposing architectural elements. In the eighteenth century, stone decorations were largely replaced by stucco interior decorations, Baroque interlace and motifs, as intensive Westernization took place. Read more on Traditional Turkish Craftsmanship

There is a widely held but quite erroneous belief that figurative painting, relief or sculpture is to be found in Islamic art due to prohibition by the Koran. Religious rulings issued only in the ninth century discouraged the representation of any living beings capable of movement but they were not rigidly enforced until the fifteenth century. Figurative art is especially rich in stone and stucco reliefs of the Seljuk period, adorning both secular and religious reliefs and tiles. The subjects included nobility as well as servants, subjects, hunters and hunting animals, trees, birds, sphinxes, lions, sirens, dragons and double-headed eagles. Some of the symbols are proof that shamanistic religious beliefs survived. The eagle was regarded, for example, as a holy bird, a protective spirit, and the guardian of heaven. It was also a symbol of potency and fertility. Eagles on tombstones or turbes reflect shamanistic beliefs that the souls of the dead rose up to Heaven in the form of birds. In Seljuk architecture, small human heads are sometimes scattered among arabesques.

Oltu Stone Carving

Erzurum has a specific local black stone (Oltu tasi, Jet) which is carved to produce jewelry, rosary beads, key-chains, pipes and boxes. Oltu stone, which has been carved in Erzurum since the 18th century, is one of the best examples of semi-precious stones to be found in the world. Oltu is excavated generally around Yasakdag, especially in Dutlu, Hankaskisla, Alatarla and Cataksu villages between March and October. There are approximately 600 oltu quarries around this area. Out of a total of 290 quarries in the Central Dutlu Region, 120 quarries are still being worked.

Jet is obtained from mountainous areas which are dug perpendicularly to the general surface and have galleries of 70-80 centimeters (27-31 inches) in diameter where only two or three miners can work. It’s a very compact velvet-black mineral of the nature of coal. Beds of this organic substance are 7-8 centimeters (3 inches) in thickness. Jet is formed when fossilized trees are subject to diastrophism resulting in folding.

The most attractive characteristic of oltu stone is that it is very soft when excavated and only begins to harden when it is exposed to the air. Therefore, it is very easy to carve this mineral. It generally comes in black, but can also be blackish brown, grey or greenish. When put near gas, this mineral bursts into flames and leaves behind a certain amount of ash. When rubbed, the oltu stone attracts, by way of static electricity, light substances such as dust.

Various ornaments made from oltu are some of the best examples of Turkish aesthetic arts. Oltu stones are mostly used to make ornaments including rings, earrings, necklaces, bracelets, tie pins, pipes, studs, cigarette-holders, and prayer beads. It is also used in the electric and electronics industries.

Even though artificial jet is produced, it is easy to distinguish the real oltu stone from the artificial. To be certain if a stone is real jet just heat a pin and see if it penetrates the stone, then the mineral is not real jet. Real jet leaves behind brown residue when scraped with a knife. When you take an oltu stone in your hand and blow on it, vapor is left on the stone.

Carpets and Kilims

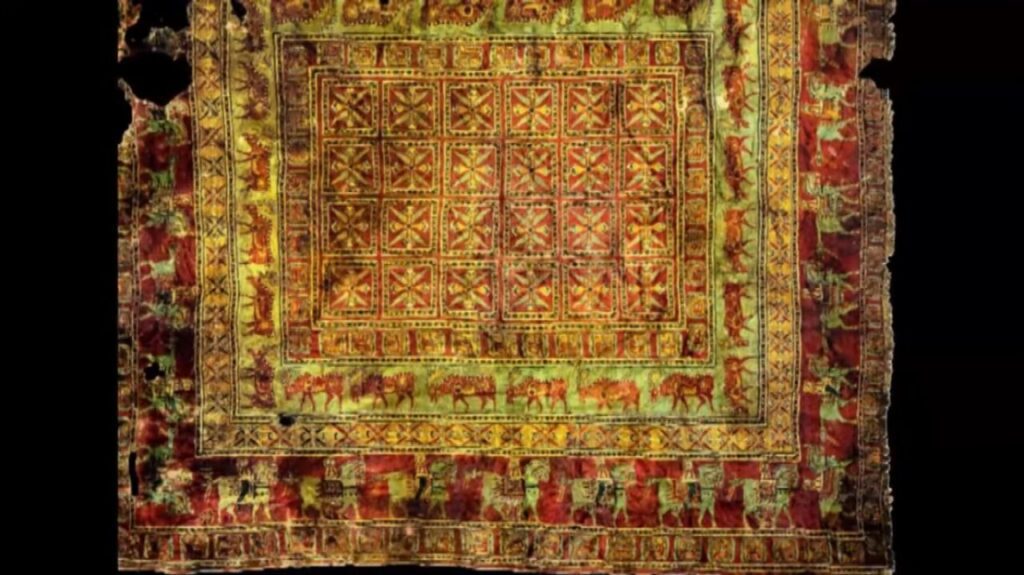

Rug weaving in Anatolia first began with the arrival of the Turkish tribes from Central Asia, who settled in this region. Therefore, Anatolian rugs form a branch of ethnic Turkish rugs. Some of the oldest examples known are the eighteen surviving pieces woven by the Seljuk Turks in the 13th century. The motifs in these pieces represented in stylized floral and geometrical patterns in several basic colors and were woven in Sivas, Kayseri and Konya provinces. The art of rug weaving which began with the Seljuks continued with the Ottomans. After the Seljuk Turks and before the Ottomans, during the transition period in the 14th century, animal figures began to appear on the rugs. Although very few of these exist today, they can be seen in the paintings of famous Italian, French and Dutch painters. Due to the animal figures on these rugs, they are called as “Rugs with Animals”.

By the 15th century there was a wider variety of animal motifs on the rugs. A new group of rugs with a combination of animal motifs and geometrical patterns appeared around this time. These rugs were called “Holbein Rugs” since they appear in paintings by the German artist Hans Holbein. As there are no surviving examples of these rugs today, all research is carried out from the paintings. The works of artists such as Lotto, Memling, Carlo Crivelli, Rafaellino de Gardo, Bernard Van Orley, Carpaccio, Jaume Huguet were also important sources of research. In this century, Bergama and Usak became important weaving centers in western Anatolia.

The 16th century was the beginning of the second successful period of Anatolian rug-weaving. The rugs from this period are called “Classical Ottoman Rugs”. The reason these rugs are called “Palace rugs” is that the design and colors would have been determined by the palace artists and then sent to the weaving centers. this method was similar to that used in the ceramic tile production of that period. The designs, which consisted of twisting branches, leaves and flowers such as tulips, carnations and hyacinths, are woven in a naturalistic style and establish the basic composition of the rug. This style was continued in other regions and can be seen in Turkish rugs today.

In the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, Gördes, Kula, Milas, Ladik, Mucur, Kirsehir, Bandirma and Canakkale gained importance as rug-weaving centers, along with Usak and Bergama. The rugs woven in some of these areas are known as “Transylvanian Rugs” because they were found in churches in Transylvania.

In the beginning of the 19th and 20th centuries, the rugs woven in Hereke (nearby Istanbul) gained worldwide recognition. These rugs were originally woven only for the Sultans of the Ottoman Empire. The finest silk rugs in the world are still being woven in Hereke today. We can identify the rugs woven in different regions as town or village rugs. The rugs woven in the agricultural areas of Anatolia owe their origins to the settlers or nomadic cultures. In Europe, these rugs (which are woven with wool on wool) are generally called “Anatolian Rugs” In towns where people have settled permanently, the rugs are woven with a wool on cotton combination.

Turkish Embroidery

Under the Byzantine Empire, Constantinople (old Istanbul) nearly bankrupted itself obtaining huge amounts of silk from China via the silk route, needed for the production of vast quantities of religious vestments and decorations. In the 6th century, a number of the closely guarded silkworm eggs were stolen by Russian monks and brought to Constantinople. Silk making quickly became a huge industry, centered in Bursa, and was inherited by the Ottomans when they replaced the Byzantines. Today, Bursa city is still an important textile center, famous for its salt-dye techniques.

The art of embroidery most likely traveled west with the nomads of the Turkic states from their Central Asian homelands. It was widely used in the military equipment of the Selcuk and Ottoman soldiers including tents, pavilions, banners, saddles and holsters richly embroidered with motifs and battle scenes, many of which are preserved in the Military Museum in Harbiye, Istanbul. Religious hangings for mosques, prayer carpets and Koranic cases were covered in graceful floral patterns in delicate colors offset with silver and gold. Many of the items of daily life, such as towels, bed coverings and veils were similarly adorned. For the Ottoman Court, silk brocades and velvets were elaborately for ceremonial purposes, often using gold or silver threads on purple velvet. Embroidery designs were based on the geometric and floral patterns used in ceramics and woven silks, though motifs and styles varied from village to village. But tulip design had always a special place in peoples heart. Some embroidery was commercially produced in workshops where men and some Christian women worked, but the quality and originality of this work was slightly inferior. The women of the harems produced magnificent work for their dowries (Çeyiz) or trousseaux and to grace their bridal chambers on their wedding nights. This art form reached its creative peak in the 16th century and then was revived again around 100 years ago with the establishment of Girls Technical Schools where it is still commonly taught. Many excellent examples can be seen in the Topkapi Palace Museum and the Sadberk Hanim Museum in Istanbul, or bought in the Grand Bazaar.

Like traditional crafts everywhere, embroidery is being killed by cheap technology. However, most grandmothers still pass their time ornamenting bed coverings and clothes for their grandchildren. The Black Sea resort of Sile near Istanbul specializes in the production of embroidered cotton clothing, towels and tablecloths.

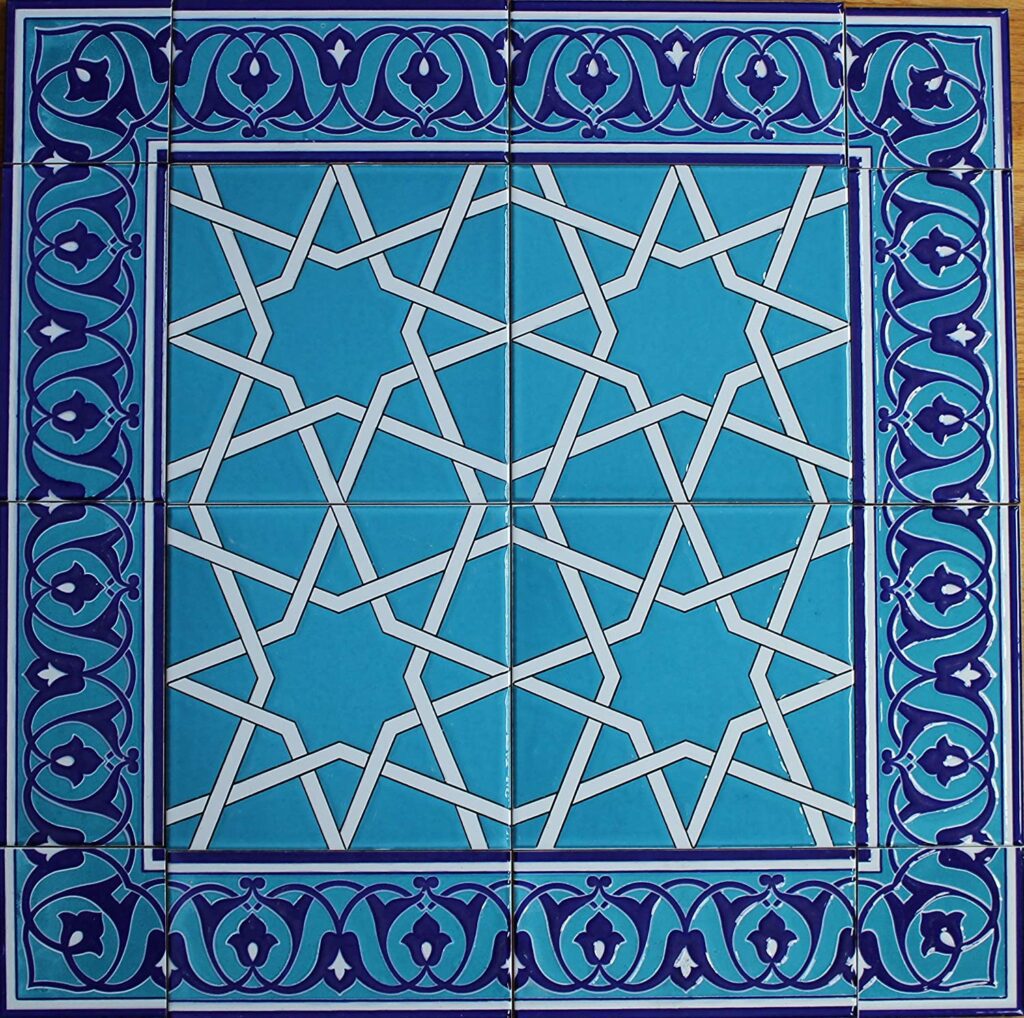

Turkish Tiles and Ceramics

As for the Turkish pottery, the best examples are from Iznik (ancient Nicea) and Kutahya. Iznik tiles are the best examples of decorated ceramics that were produced between 15th and 17th centuries in that town, and were widely used in decorating the mosques and palaces. These exceptional pieces represent the cultural and artistic zenith of the Ottoman Empire. After Iznik, Kütahya was the most important center for ceramic production especially between 17th and 18th centuries, altough earliest examples dates back to the 14th century. Today, both Iznik and Kutahya ceramics are produced therefore this traditional ware has survived to the present day.

Turkish Fine Arts

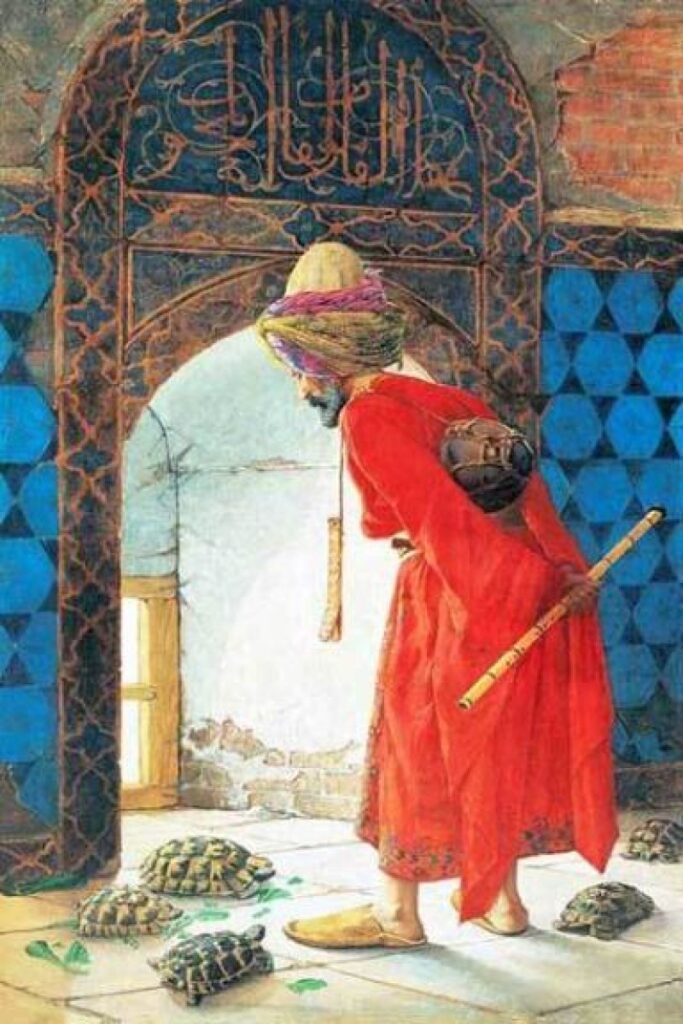

Turkish Painting

Islamic Art varies substantially from Western Art due primarily to restrictions in the Koran on depicting the human form. Rather than being representational of the profane world, the perfection of Ottoman art lies in the pure balance of color, line and rhythm in geometric patterns and designs. Turkish painting in the western sense only began in the 19th century, with the founding by Osman Hamdi Bey, himself an accomplished painter, of the Academy of Fine Arts. Turkish painters were sent to France and Italy by the Ottoman Sultans, and foreign painters, mostly Italian or French, were brought from Europe to live as court painters and transfer their skills. Today this academy is known as Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University. Among the best known of the early Ottoman painters, besides Osman Hamdi Bey, we can name Seker Ahmet Pasha, Hoca Ali Riza, Sevket Dag , Ahmet Ziya and Halil Pasha. They were primarily landscape painters, with few portraits. In 1919 the Ottoman Society of Painters held their first exhibition in Galatasaray – Istanbul. Following the War, impressionism was a major influence on Turkish painters. The most successful impressionist painter was Halil Pasha. Painting continued to develop through the thirties and forties, with increased emphasis on design and subject matter. The abstract and cubist movements were popular in Turkey, the best known painters in this genre are Sabri Berkel, Halil Dikmen, Cemal Bingöl and Semsettin Arel. Today’s Turkish artists are no longer bound in subject or design by their past, and a wide range of techniques and approaches are being used by the many artists at work today. There is an ever – increasing number of art galleries showcasing these young talents, with regular exhibitions of new work.

Turkish Sculpture

From a historical perspective, the vast lands in which Turks existed, starting from pre-historical times have been places where great civilizations have grown and lived, consequently where sculpture production have been widespread. Turks living in Central and Asia Minor have made sculptures for different reasons in the pre-Islamic time. After the acceptance of Islam, sculpture with religious quality and worship purposes were prohibited. Since there was no prohibition against description of non-religious nature, it was especially possible to realize stylized plant, animal and human sculptures in Seljuk art.

Although Seljuks developed a sculpture dependent of architecture, the classical period of architectural conception of Ottomans was based on simplicity, monumentalism, geometric and abstract forms. For this reason Ottomans stayed distant to sculpture that could take place in this frame until the ends of the 19th century. They had only produced sculptural examples in tomb-stones, marking stones and bow figures of lions.

The acceptance of sculpture as part of art in Turkey in modern sense is realized in 1883 with the founding of Sanayi-i Nefise Mektebi Alisi / School of Fine Arts. Osman Hamdi Bey was the founder and first principal of the school. Sculpture, that was less popular compared to painting, found the possibility of development after this date within the environment of the school.

Turkish Photography

Photography was one of the major technological discoveries that contributed to the rise of modernity in the 19th century. It was introduced to the lands of the Ottoman Empire by travelers and became widespread in the end of the 19th century. The first professional photography studio in Istanbul was established in 1845 by Italian brothers Carlo and Giovanni Naya. Vasilaki Kargopoulo was the first Ottoman to establish a studio in 1850. Following the 1860s, the number of such studios increased significantly, and they were mainly located around the Pera and Kadıköy districts in Istanbul. Sultan Abdülhamid II (r. 1876-1909) had an interest in photography and took photographs himself. During his reign, the art of photography developed rapidly in the Ottoman Empire. The Sultan commissioned photographers to document events and principal institutions in the country. In 1893 Sultan Abdülhamid II sent 51 photograph albums to the Library of Congress in the United States and 47 photograph albums to the British Museum in England to introduce the Ottoman Empire.