Essential Turkish Cuisine

Introduction

Turkish Cuisine : There is a very close connection between the food and nutrition culture and gastronomic values of each nation. Eating habits are considered a cultural element; therefore, they differ according to the culture of a society. The taste, quality, and food types in the Turkish society are rather different than those of other societies. The Turkish nation possesses a very well-established history and high cultural structure. Unquestionably, a sub element belonging to a rich culture is also correspondingly rich. The art of cooking, imparting nutrition, cooking and storage methods, use of tools, and food and drink services show the crux of this culture.

Turkish Cuisine History

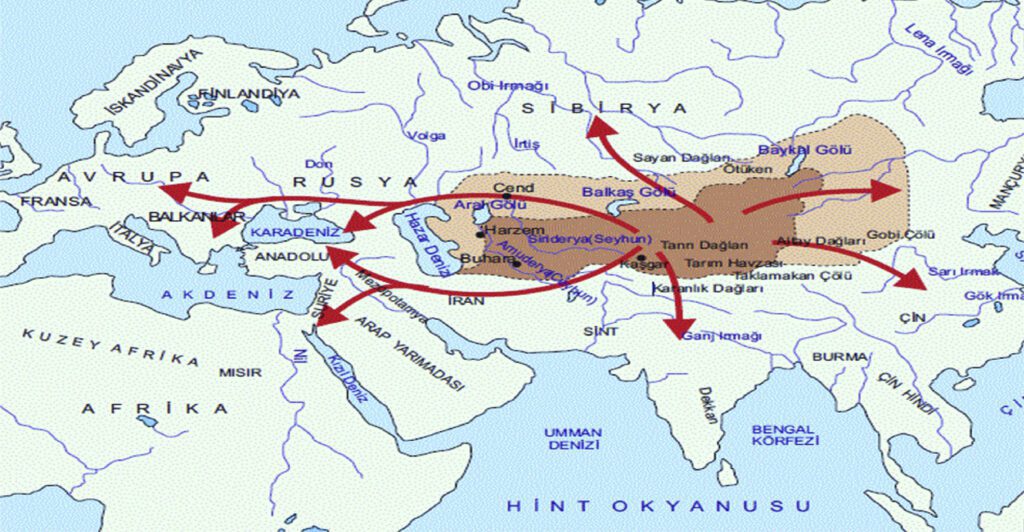

The historical development of Turkish cuisine is directly related to the vast geography the Turks have lived on and the ingredients that these geographies have offered, enabled Turks to form a very rich and varied food culture. Read more about Turkish Desserts

Eating and drinking habits in ancient Turks

The Turks of Central Asia earned their living via animal husbandry. Animal milk and milk product consumption was important because ancient Turks were mostly engaged in livestock farming. In view of that, they find mentions in Turkish mythology. Portraits of camels, cattle, sheep, and goats drawn by Turks have been seen on the rocks in their settlements. Information in regard to the Central Asian region before the year 1037 is limited based on available evidence. Some information related to the types of food in the Seljuk period such as muffins, thin dough, bread, halvah, koumiss, buttermilk, and molasses, excluding meaty dishes, has been mentioned in Kaşgarlı Mahmud’s work (book). Based on information about various food preparations mentioned in “Divanü Lügat’it-Türk”, it could be understood that there was high demand for sour yogurt and sour foods mixed with ingredients such as vinegar among Turks in the 11th century. This indicates that sour foods had a special place in the Turkish cuisine and probably appeared to be a characteristic feature of Turkish cuisine after the 11th century

Gastronomy in the Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate

The most significant state that was formed in Anatolia were The Anatolian Seljuks. Encountering many new and different ingredients, Seljuks incorporated them into their own cuisine. The once simple cuisine, became more complex with the addition of new ingredients and new cooking methods. Seljuks ate meals twice a day. The first meal was a “midmorning meal” and the second one was “dinner.” Except during Ramadan, elaborate meals were not seen in the Seljuk state. Humble dishes, without a variety of food, were served among themselves on dining tables. Most people ate a part of meal (breakfast) at sunrise. This dish generally consisted of soup, cheese, and bread. At the end, coffee was served. During Ramadan, parents gathered together with their closest friends. Charity, philanthropy, and hospitality were not forgotten. When people came up to the table during a meal, welcoming them to the table and opening the meal was the most natural thing.

During the Anatolian Seljuk and Principalities period, sherbets prepared from a variety of fruit and honey or sugar were the most common type of beverages and a source of income. During these periods, wine was among the main drinks consumed widely. A drink produced from barley or wheat mixed with vinegar and honey was known as Mevlana‘s admired mixture “sirkencubin” and was, however, prohibited by religion

Ottoman Cuisine

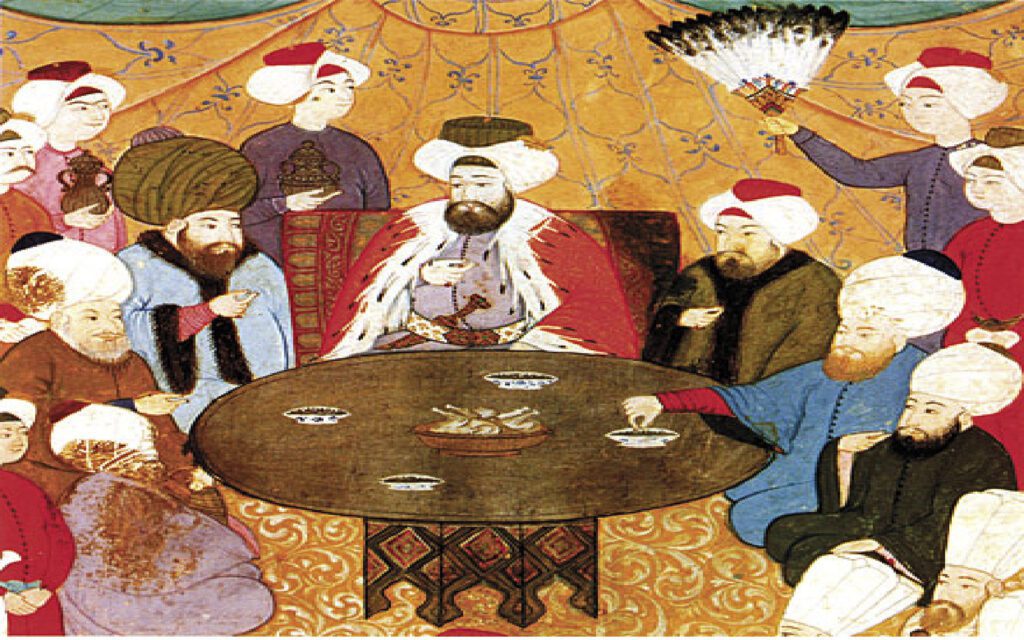

Fall of the Anatolian Seljuks also marked the beginning of the Ottomans. The foundations of today’s Turkish cuisine lays in the Ottoman palace kitchen. The culinary culture of the Ottoman Empire was divided into two: the palace kitchen and the public kitchen. The palace kitchen was further divided into the sultan and harem cuisines and consisted of showy tables meant for the sultana and the council people. To feed the crowds in palace surroundings, the cooks often invented new dishes. The cooking team, reaching up to 1200 personnel, prepared food for not only people in the palace surroundings but also incoming guests

Palace cuisine

The development of the palace kitchen was started through building new kitchens inside the Topkapi Palace in the second half of the 15th century by Mehmed the Conqueror. These kitchens, with its many domes and chimneys, were located in the southern part of the Topkapi Palace; the name “New Palace” was granted. When Istanbul was captured in 1453 by Mehmed the Conqueror, many changes occurred in Ottoman palace foods. During this period, the consumption of seafood increased considerably. For Ottomans, cuisine was an important part of palace life. They considered the gathering of sultan and senior officers along with noblemen a social activity; therefore, the palace cuisine was always looking for improvements, became a place to look for a variety of tastes, and brought rich food into existence. The cooks competed with each other to prepare the dishes preferred by the sultan and people surrounding him and to make the banquets attractive, which contributed to enrichment of Turkish cuisine

Sultan dining table

The meals for a sultan often included poultry meat and were prepared by the top responsible chef and were brought to the dining table by maids on duty. During this period, meals in the palace were eaten twice a day. In contrast to the breakfast that we are accustomed to today, the palace breakfast was a meal that always included hearty soup. The sultan sat according to certain Turkish practices with his knees crossed and a valuable towel placed in the front to prevent his clothes from staining. A second towel was placed in his left hand to clean his mouth and fingers. The meat served to the sultan was brought intact and was not torn into pieces. The sultan himself tore the meat into pieces, and he never used a fork or knife for the same. As the meat served in his meals was very soft, he could easily eat it with the use of his fingers without the need for a knife. The sultan drank only soup with stewed fruit during his meal; after the meal, some sherbet was served

Harem dining table

The meals of harem people, princes, and sultans were prepared in a special kitchen. Women called Iqbal took part in the harem kitchen. An Iqbal with a child was designated as woman. The harem ate their meal in the order asked by the sultan. All meals were served in tinned copper plates. The plates were always clean and bright. Some plates were made of white porcelain. The harem had a unique dish for itself. The sultana, wives of sultans, Haseki sultans, treasurer masters, and the primary dearest women each had a separate dining table. The meals were eaten together on these dining tables; the sultan had no connection with the food ceremony there. It is seen that the organizational structure of palace cuisine began to be institutionalized during Murad II’s period

The simple public kitchen

Compared to palace cuisine, public cuisine was fairly simple and had fewer varieties. The meals were eaten twice a day following the haremlik–selamlik order (men and women sat separately at that time). In modest houses where the haremlik–selamlik order was not practiced, everyone, including men, women, and children, ate their meals on the same dining table. In such houses and in institutions where collective meals were served, a soup was served with a main meal, although the Ottoman dining tables had a rich variety of food. Based on religion, collective meal invitations were offered on festival days, sahur, iftar (early breakfast during Ramadan), and prayers for rain besides weddings, engagements, circumcision ceremony, and funerals. During the Ramadan month, master cooks were brought to mansions to prepare varied good meals. It is possible to find different food samples in different parts of Anatolia in the Ottoman period

Gastronomy in modern Turkey

Foreign impact is seen along with reforms in the cuisine manners of the Republican period. The habit of eating meal in a different dish is increasing day by day. The reason for this change is that everyone around the dining table shall benefit with equal amounts of food on the table or get enough food as per their capacity . Even now, the majority of the rural areas continue to dine around the tray. In recent years, cuisine has been influenced by globalization; all kinds of food and spices in the world have entered all cuisines

In today’s Turkey, food culture varies from region to region. Eastern Anatolia, Southeastern Anatolia, Black Sea, Marmara, Aegean, and Mediterranean regions have their own food cultures. In the Black Sea region, we can give a few examples representing the food wealth. For example, over 20 dishes are made from the known mixture of corn. Dishes made from anchovies such as stuffed fried anchovies, anchovy bread, anchovies rice, anchovies pan and meatballs, anchovies boiled, anchovies grill, and anchovy patty show how rich the Black Sea cuisine is.

Vegetable and olive oil–based dishes are common in Mediterranean cuisine, specifically in the Mediterranean regions of Turkey. Olives have been used in Mediterranean cuisine for 2500 years . After olive oil, the most important factor shaping the Aegean cuisine is herbs available in the region. Countless types of herbs exist therein. In case we count the main herbs used in Izmir, we get a long list: vine, hibiscus, nettle, arugula, parsley, radish sprouts, thistle, chicory, poppy, dock, Kushto of plantain, blessed thistle, dandelion, Helvajik, asparagus, tangle, samphire, etc. These herbs are more consumed in Izmir and the entire Aegean coast. In addition, there are many types of herbs that are edible and grown in nature and are very important for their economic and cultural value in Turkey. These herb salads are commonly consumed in season.

Traditional Mediterranean cuisine is generally based on grains (especially wheat), olive oil, fruit and vegetables, seafood, dairy, and spices. In the Aegean, Marmara, and Mediterranean regions, olive oil–based vegetable dishes are generally consumed in cold conditions. Salads prepared from raw or cooked vegetables are mostly flavored with lemon, vinegar, and olive oil. The shepherd salad made with onion, tomato, beans, and pepper and served as an accompaniment to the main dish; lettuce salad prepared with green vegetables; the salad known as haricot bean salad prepared with legumes also exist in Turkish cuisine. Bulgur salad with walnuts and salad prepared with vegetables and bulgur are available as well. Vegetable dishes are also important in the Aegean cuisine. Artichokes, beans, and eggplant belt are often cooked

Common Traditions

People in the Republican era sit at the table after washing their hands first. Generally, the father starts eating by saying “bismillah.” He opens the meal by saying “enjoy” or “scar.” A Turkish dining table without soup is unthinkable. Soup is consumed with any kind of meal in Turkish cuisine and is served at the beginning of the meal; it is served hot. There are other soup types even more important than scalded meat and soups made from aquatic chicken, which generally may be divided into three groups: floury, grain, and strained-grind soups. Toyga (soup made with yogurt, hazelnut, rice, egg, and mint), arabashe (a kind of spicy chicken soup), wedding soup, and tomato soup are examples of floury soups; tutmach, grain soup, strained-grind rubbed noodle soup, lentil soup and vegetable soup can be given as examples of strained-grind soups. In terms of nutrition; especially Tarhana soup, yogurt soup and lentil soup adding mincing meat is common. Yogurt and rice together with chickpea being served with a vegetable salad and a vegetable dish forms a balanced food. Turkish cuisine is famous in the world for its meat dishes such as raw and doner kebab made from mutton and lamb. In Turkish cuisine, doner, fried food, roast, grilled kebabs, pot kebabs, stews, casseroles, field food, fish stews, boiled, meatballs, meaty stuffing, fruity meat dishes and a many more varieties of food are cooked.

Meatballs are the most commonly cooked meat. Besides mixing meatballs with ground beef and various ingredients, the types prepared with bulgur are also available, especially in the southeast, east, and Mediterranean regions. On the basis of health, mixing ground beef or bulgur with vegetables and baking it in the furnace, plate or in the aqueous medium is considered a very healthy practice. Foods cooked in pans, jerks, moussaka, wrapped and stuffed food, and vegetable and olive oil–based dishes are the types of vegetable dishes available in Turkish cuisine. Eggplants, peppers, or zucchini are prepared directly or with flour by being fried in oil and are served with sauce. Vegetables are fried before using ground beef in moussaka.

Bread is a sacred food among Turks. It has a religious importance. They have infinite respect toward bread, mankind’s main food. Sometimes, even vows had taken place onto bread. Bread is the most irreplaceable food item on Turkish dining tables and is the most respected nutrient and placed in safe corners. Bread is considered the most precious divine blessing; thus, it is always referred to with special reverence. In general, three kinds of breads, namely, loaves, flatbread, and yufka are consumed. Most of the time, bread is used as a meal with one or two additives.

Ramadan

A significant portion of our culinary culture which has developed around Ramadan has to do with preparation for the month. In Ramadan of old when, unlike today, every sort of fruit, vegetable and dried goods were not found throughout the year, foods and ingredients that would be consumed during Ramadan were prepared or bought during the seasons when they were cheap and plentiful.

The foods that were bought or prepared ahead in large quantities and known as ramazanlık or ramazaniyelik were of special importance when Ramadan fell during the winter months. Some foods bought for Ramadan which indicate the richness of our cuisine include pastırma, sucuk, kavruma and other meat products, dried green beans, eggplant and red peppers, various pickles, cheese and oils, soup ingredients, especially tarhana, preserves, marmalades and fruit leathers, ingredients for compotes such as sour cherries, apricots, plums etc., bulgur, noodles, rice and pasta, tomato and pepper pastes, dried yufka and other breads.

It was important that such foods be bought or prepared in quantities sufficient to last at least a month. Ingredients such as flour, oil and sugar, which at other times were bought weekly or daily, would be bought in large bags or tins to last throughout Ramadan. In some areas, this is known as ramazan tedariki, or Ramadan procurement.

The Month of Muharrem (Aşure Month/Day)

The month of Muharrem is also called Aşure month, after the dish aşure, a special wheat pudding, which is cooked without fail during the month. The aşure is cooked on the 10th or 11th day of Muharrem, and distributed to friends and neighbors, and served to visitors. Especially those who sacrifice an animal must prepare aşure. The ingredients used in aşure, which is said to have first been made by Noah and his family with the last of all the provisions on the ark after the flood, vary from region to region. In some areas, a piece of the tail fat, or in Zonguldak and Devrek provinces, a piece of the meat is hidden in the aşure.

In Denizli, keşkek as well as aşure is prepared, and distributed with the aşure. According to Nevin Halıcı, in Uşak there is a tradition of a “Three Pots Invitation” (Üç Tencere Daveti), in which soup, meat and rice is eaten, after which the aşure is served. Aşure is also made outside of Muharrem as well. In Thrace, aşure is sure to be included in the “Güvey Yemeği,” the meal served in the home of the groom the day after the consummation of the wedding.

Kandils

Kandils are special days commemorating major events in the life of the Prophet Mohammed: his conception, birth, receiving of the Koran, his ascent into heaven, and his death. In most regions, certain sweets are made and distributed on each Kandil, but in some areas, the first Kandil is celebrated but nothing in particular is done for the second or thirds unless there are special local traditions. The second Kandil is the Miraç Kandil, the commemoration of the ascent. In Izmir and Denizli, milk is distributed on this Kandil.

A sweet known as lokum or lokma is made in almost every region and distributed among friends and neighbors. Halva is as common as lokma for distribution. In Zonguldak and Devrek, a börek with walnuts is prepared and distributed in front of the mosque. The Kandil çöreks/simits, with or without sesame which are common today are another food especially associated with the Kandils.

Hıdrellez

Generally celebrated on May 5-6, Hıdrellez is a seasonal festival which celebrates the coming of spring, the waking up of nature, and includes certain customs which people peform with the hope of having their wishes granted. On that day, people go into the country, and special items placed into a clay pot are drawn out as wishes are made and manis or quatrains, are sung.

In addition to all this, certain foods are prepared especially for Hıdrellez, and taken into the country, where people celebrate, dance and eat together. Generally these are easy-to-transport dishes. Lettuce salad, boiled eggs, stuffed grape leaves, bükme, çörek, börek,layered bread with tahini, ribs, a dish made from roasted wheat flour and gözleme (stuffed thin pancake) are examples of such foods. In some areas an animal is slaughtered, andkavurma and pilaf is made from its meat. In Muğla and Izmir, milk is drunk with the belief that it is curative, and it is considered good to eat greens.

Henna Night

The night before the wedding, the bride’s palms are filled with henna and her hands are bound; this is known as henna night. The serving of food has a very important place on the henna night. The foods include pilaf, meat dishes, noodle soup with chickpeas, rusks, and poppyseed pide. The sweets include lokma, koz helva, zerde, rice pudding and halvah.

Zonguldak and Devrek, bread is broken and distributed among those in attendance. In other regions, this same tradition is performed on the henna night, for the same purpose.

Turkish Cuisine Ingredients

The great variety of ingredients grown or found within the Turkish geography have enabled Turks to develop many different types of food products. Whether they were invented out of a need or simply to make use of the surplus products they each have been a great addition to the Turkish culinary culture. Yogurt, “kurut” (dehydrated yoghurt), “pastırma” (salt cured beef), “cevizli sucuk” (the jelly-like candy with walnuts in the center) are some of these products unique in Turkish cuisine that are still consumed in the present.

Importance of Grains and breads in Turkish Cuisine

Grains

Tahıl is the name given in Turkish to the dried seeds of plants in the grass family (Poaceae), which eaten either whole or ground into flour. The word hububat is also used. Grown the world over and with a history almost as old as humanity itself, they may be consumed in a variety of ways but the thing they have in common is the making of bread. Though many different grains are used to make bread, the most commonly used is wheat. Other than wheat , oat, barley, millet, corn, rye are commonly used.

Across the vast Turkic region from Central Asia to the Mediterranean basin, the most used grains are wheat and barley, mostly used in the form of flour. Bread is an indispensable part of the Turkish table; it is not only a staple source of nutrition but has also become a central element of Turkish culture. In Turkey, bread is sacred. This sacredness comes from the fact that not only is it a natural product, but also the result of great effort. Used synonymously with both “food” and “work,” bread has a value distinct from all other foods.

Turkish Bread Culture

Bread is the Turks’ fundamental staple. Daily bread consumption changes according to individual characteristics and habits, life and work styles and diets. Those who engage in much physical labor consume more bread than those who engage in little physical labor. The Turkish word for bread, ekmek, pronounced etmek in old Turkish, as well as ötmek in some regions. In some Ottoman Turkish sources, it was written as “etmek” but pronounced as “ekmek.” It appears in the Divan-ı Lügat-it Türk as “etmek”

The Turks made a great variety of bread from the wheat they mill, and these products had an equal variety of names, sometimes based on the manner of cooking, and other times based on their appearance. Traditional bread was mostly baked at home in an oven called a tinürü(mod. Turkish: tandır). It is recorded that for feast days, differently flavored breads were created with the addition of butter, spices and fragrant herbs. Some of these flavoring agents include salt, cumin, nigella seed, fennel, saffron, sesame, mustard and watermelon seeds. Some areas had breads that had become locally famous. For example, it is stated that the King sent Karkamış bread to Lasmah-Addu, along with wine and various other gifts. As there were vineyards in this region, it is thought that this bread could have been a raisin bread. During later years, paper-thin yufka bread made its appearance with the nomadic people of Asia. The long keeping properties of yufka bread was important for the Turks in their nomadic lifestyle. It is written that eight to ten of these thin yufkas were stacked and then rolled. During the summer it was preferred to other breads because of its long lasting properties.

A similar bread to yufka is lavaş. Thin pide was known as yufka in both Azerbaijani and Çağatay Turkish. In addition to these breads, there are types of breads made with corn, barley, millet and wheat flour, leavened and unleavened, with and without oil, thin and thick, sweet and unsweetened, and cooked on a convex griddle called a saç. Another type, known as sinçü, resembled modern-day pide. A type of cookie called çukmin comprised yet another type of bread. As many different names as there were, we must accept that there were some that did not resemble breads, such as çörek, pide, etc. It is recorded that Turks in the 11th century were making various çöreks which resemble those made today. Among the various types of çörek was kömeç (<kömmek, mod. Turkish gömmek, “to bury”) which was made by burying the dough in hot coals, and which survives today by the names gömeç-gömbe-kömbe and göbe-göbü.

Bread has an extremely important place in Turkish cuisine; it is the basic staple. Whatever type of bread it may be, people think of how to earn their daily bread, so much so that the term ekmek parası is applied to money earned, or the recompense for one’s labor. This is a clear indication of bread’s importance in daily life. Read more on Turkish Bread

Vegetables

Turkish cuisine is quite rich in its use of vegetables. Both the use of a wide variety of vegetables as well as a wealth of manners of preparation are indicative of the richness of Turkish cuisine. Cucumber, Arugula, Asparagus, Artichoke, Beets, Cabbage, Carrots, Cauliflower, Celeriac, Chicory, Eggplant, Garlic , Knotweed, Leeks , Romaine Lettuce , Mallow, Okra, Onions, Parsley, Peppers, Potatoes, Purslane, Spinach, Radish , Tomatoes, Turnips, Zucchini are widely used in Turkish cuisine.

Wild Herbs

There are more than ten thousand plant species in Turkey, more than in all the countries of Europe combined. Many these are edible, and many are endemic, meaning that they grow only in Turkey. It’s a great treasure that should be appreciated. While some of these are well known throughout the country such as nettles, mallow, sage and thyme, others are only used in a very small area, such as sarıot (Opopanax hispidus), baldıran (Black lovage,Smyrnium olusatrum) and mendek. While some are used more medicinally, others add fragrance to our food, others increase the food value of cheese, and yet others add variety to the table during winter when other vegetables are lacking. It would be difficult to include all the wild herbs of Turkey in one article, so here we will deal with the best known of them, their uses and characteristics. Some of wild herbs usen in Turkish cuisine are;

Fennel, Bittersweet, Crocus, Foxtail Lily, Samphire, Mallow, Illyrian thistle, Wild Lettuce, Corn Poppy, Wild Mustard, Wild chicory, Borage, Stinging Nettle, Wild Rhubarb, Cranesbill, Dandelion, Rock Samphire, Sicle Weed, Gundelia tournefortii, Shepherd’s Purse, Chickweed, Dog’s Cabbage, Sorrel, Dock, Knotweed, Black Bryony, Purslane, Greenbriar, Chenopodium, Lesser Water Parsnip, Watercress, Golden Thistle, Salsify, Wild Radish, Wild Asparagus, Wild Chard, Wild garlic

Fruits

Due to its rich natural vegetation, Turkey is one of the richest countries in the world in terms of fruit production. Its regional differences in climate and soil type provided a ready environment for the cultivation of fruit as well as vegetables. One may find hundreds of varieties of a single fruit, this is especially true in Turkey for fruits such as pears, apples and grapes.

Besides eating fresh, fruit may also be consumed stewed or prepared as compotes or drunk as sherbets, as well as made into preserves. Turkish cuisine brings fruits to the table in many different and unique ways. Read more about special article about Turkish Fruits

Fish and Seafood

Bordered on three sides by seas, crossed by great rivers and creeks and lakes, Turkey is practically a great nation of water. The fish living in these bodies of salt and fresh water hold an important place in this culture’s cuisine. The fish in countries like Turkey, which has inland seas, are especially flavorful. This is because such fish have many bottom and active mid-water fish, and these are more flavorful than open-sea and ocean fish. In addition to the flavor of these fish, Turkey is a wealthy country from several standpoints. Every sea has its own naturally-occurring fish, and each has its own season and special flavors. The hamsi of the Black Sea, the istavrit of the Marmara Sea, the sardines of the Dardanelles and the sea bream of the Aegean are fish which are immediately identified with these waters. Other fish such as mackerel, tuna, turbot, bonito, çinekop (small bluefish) and lüfer (adult bluefish) have a special flavor in each sea in which they occur and bring a different flavor to the table.

There are three main ways of preparing fish in Turkey: grilling, frying and steaming. All three are used in homes and restaurants, according to the type of fish and the season in which it is caught. Dishes of which fish is a component are more common among people who live along the coasts than inland. In addition to fish, Turkey has an abundance of other seafood as well, such as mussels, oysters, octopus, squid and shrimp.

Meat and Offal Products

The beauty of Turkish cooking is its amazing clean tastes along with affordability. Fresh ingredients are ever present and abundantly used. There is a fairly routine method for cooking most main dishes. This is highly tasty and effective are served simply and rarely hidden under sauces. Using stunningly tasty, fresh, seasonal ingredients makes for a wonderful cuisine. It’s delicious flavors are hard to beat and harder to forget.

Lamb

Lamb is considered to be the meat of sheep under one year old. It is lightly fatty. Milk-fed or suckling lambs range from 4 – 9 kilos and are generally available from January to late March. Those from 10-15 kilos and available from May to December are grazing and have a different quality of meat.

Mutton

There are three breeds of sheep in our country: Dağlıç, Karaman and Kıvırcık. Kıvırcık is the most desirable. Whatever the breed, the male is more desirable than the female.

-

Kıvırcık

Kıvırcık sheep have long, thin tails and are considered the most desirable for meat, it is divided into two sub-breeds, Karnabat and Merinos. The meat of Karnabat is pink and flavorful. Merinos is darker and may be slightly gamey. -

Dağlıç

There are two sub-breeds, white (Beyaz) and Black (Kara) Dağlıç. The white variety is preferred. The tail of the white dağlıç is broad at the base and divided halfway down, with a tassel-like end. The black dağlıç’s tail is narrower at the base and the tassel at the end is quite long. -

Karaman

Karaman sheep are also divided into sub-breeds, Beyaz (white) and Kızıl (Red). The white breed has very white meat which is preferred over that of the black dağlıç breed. Red Karaman is considered the worst mutton. The white Karaman has an upward-turned swelling in place of the tassel on the tail. In the red variety, there is a second large swelling on the first.

Goat

Less flavorful than mutton/lamb. Kid meat is perferred.

Young Veal

The meat of calves from 2 to 12 weeks of age is considered young veal. It is less fatty than the meat of weaned veal.

Weaned Veal

Preferred over young veal, good veal should be brilliant red. As it is less fatty, it is especially preferred for mincemeat.

Beef/Steer

There are two varieties, Trakya (Thrace) and Erzurum, with the Trakya variety being more flavorful and less fatty. It’s meat is pinkish, with lemon-yellow fat. The other has darker meat with darker yellow fat. The meat of cows is preferred over that of steers.

Water Buffalo

Water buffalo meat is pink with white fat, the main feature which distinguishes its meat from beef. The females are preferred.

Poultry

- Chicken

- Turkey

Spices

Herbs and spices have been used by mankind since ancient times for a variety of purposes. Sometimes a wild flower, the bark of a great tree or the fruit of a bush, spices show infinite variety in their form, characteristics and function. Here we will mention the spices used traditionally in Turkish cuisine, as well as those which have entered our food culture in more recent times:

Allspice, Anise, Arugula, Rocket, Basil, Bay leaf, Black Pepper, Cardamom, Cinnamon, Cloves, Cress, Cumin, Coriander, Cilantro, Curly Parsley, Currants, Curry Powder, Dill, Fennel, Fenugreek, Ginger, Juniper, Marjoram, Mint, Musk Plant, Nigella, Nutmeg, Parsley, Pine Nuts, Poppy Seeds, Red Flake Pepper, Rosemary, Sage, Saffron, Sahlep, Sesame, Sumac, Tarragon, Turmeric, Vanilla, White Pepper, Wild Thyme

Read more about where you can buy these spices

Drinks

The richness of Turkish cuisine is known the world over, mainly in terms of its variety of dishes and ingredients. However there is also a great variety of traditional drinks.

Hot Drinks

The most common hot drinks in turkey are tea, coffee, linden tea, sage tea, cinnamon tea, milk and salep.

Tea

Tea was introduced to Europe in the early 17th century. It was first raised in Turkey in Batum (present-day Georgia) in 1918. Tea is one of the most loved drinks in our country; so much so that even in the smallest of villages, tea will be available in the coffee house if nothing else. The coffeehouses and teahouses in our villages, small towns and cities are truly indebted to tea. Tea has created its own material culture as well. Samovars are part and parcel of traditional Turkish tea culture; other items include the typical Turkish double tea kettles, tea glasses and small spoons, and trays. Read more about Tea Culture in Turkey

Linden

One of our other hot drinks is linden tea, also known as lime, because of the fragrance of the flowers. It is mostly drunk at home, medicinally. It is diuretic, causes perspiration, has a calming effect and clears the chest. For this reason linden has recently begun to be offered at workplaces as well. Workers who for health reasons prefer not to drink black tea all day, choose linden tea instead.

Sage Tea

Just like linden, tea brewed from sage is drunk hot. It is especially popular in Western Anatolia where it can be found in coffeehouses and teahouses.

Cinnamon

This is drunk as tea in various regions, where it is enjoyed for its flavor and color, and has begun to appear in coffeehouses and workplaces.

Coffee

Coffee was first raised in Arabia in the 15th century. It reached Turkey in the 16th century, and the brewing technique used here has become know the world over as “Turkish coffee.” However it is not raised in Turkey. Coffee has become a “lubricant” for conversation in Turkey, as shown by the saying:

The heart desires neither coffee or a coffeehouse

The heart desires a companion, coffee is but the excuse

The expression “come on, let’s have a coffee” does not mean simply to have the physical cup of coffee. One treats a friend to a cup of coffee in order to have a conversation, to share ones sorrows or to gossip. The expression “a fatigue coffee” means to relax. Another interesting expression is, Bir fincan acı kahvenin kırk yıllık hatırı vardır. This means, “One cup of bitter coffee is remembered for forty years.” This refers to the reinforcement of relationships and friendships over coffee. The practice by Turkish women of reading fortunes in coffee grounds is psychologically comforting, as it does away with worries about the future. When a matchmaker goes to a home, or a family goes to speak the family about a prospective marriage, it is traditional for the girl to serve coffee. The real reason behind this is for them to see the girl. Traditionally, it was unacceptable for children and young people to drink coffee together with adults; to do so was considered disrespectful. The real reason for this was to keep young people from becoming involved in the adults’ conversations. Of course there is also the issue of coffee being harmful to young people’s health. Coffee is served plain, slightly sweet, medium sweet or sweet. It is also fairly common to add milk to coffee. Like tea, coffee also has its own material culture, including all manner of coffee cups, cezves (Turkish coffee pots), hand coffee grinders, mortar and pestles for coffee (dıbek) and trays. Read more on Turkish Coffe Culture

Salep

With the coming of cold winter days, Turkey’s cake and pudding shops begin serving salep in place of ice cream. On the ferryboats which ply their way between the European and Asian shores of Istanbul with smoke trailing from their funnels and chased by flocks of seagulls, many of the passengers order steaming cups of this delicious warming beverage. It is made from the powdered root of several species of wild orchids and is both tasty and nourishing. It keeps the body warm in cold weather and increases resistance against the colds and coughs of winter. The Turks have been drinking it for many centuries. After they became converted in the 8th century to Islam, a religion that prohibited the consumption of alcoholic drinks like wine and kimiz (made from marsh milk), non-alcoholic beverages like boza (made from maize) , sira (grape juice) and it took their place. While sira was the preferred drink of the summer months, boza and hot salep were the drinks of winter. Also known as cayirotu or cemcicegi, salep is believed to be good for disorders of the intestines, colds, and coughs; improve the appetite and increase virility. Ancient folklore relates that it was an ingredient of love potions brewed by witches. Today it is more common in the large cities, and is especially common at breakfast, but is not much made at home any more.

Cold Drinks

Boza

One of the most popular wintertime drinks, boza is a fermented and hick, sweet-sour drink beverage that has a history in Turkey. Fermented drinks from cereal flour or millet first made their appearance during the 9th and 8th millennia BC during the time of the native Anatolians and Mesopotamians. During the 10th century, the drink gained the name ‘boza,’ and became popular among the Central Asian Turkic people, later spreading to the Caucasus and the Balkans. Under the Ottoman Empire, where everything related to the culinary world flourished, boza also enjoyed its golden era. Due to a very low but present level of alcohol, the drink faced some problems in the 17th century when Sultan Mehmed IV prohibited the consumption of alcoholic drinks including boza. After this ruling, the prohibition was reinforced and loosened several times over the course of history, until a sweet and non-alcoholic version was introduced in the 19th century and became much more popular than its sour and alcoholic predecessor. It was during this time, 1876 to be exact, that brothers Hacı İbrahim and Hacı Sadık established a boza shop in Istanbul’s Vefa district that continues to serve the city’s most iconic boza. When Vefa Bozacısı opened, it quickly became a favorite among the sultans and the aristocrats that used to inhabit the neighborhood. Run by the original owners’ great-great-grandchildren, Vefa Bozacısı is still the most nostalgic place in Istanbul to try the drink in all its traditional glory.

Sherbets

Before the spread of fruit juices in our country, cold drinks called “sherbets” were very popular. In the old days, a sherbet called Lohusa şerbeti was served, especially at births. (Loğusa < Gr.lehousa, a woman who has just given birth). The same sherbet was also served at engagements and the söz kesilme, the traditional “promise” between a man and a woman prior to their actual engagement. There were many different varieties of sherbet; some that appeared in the poetry of Mevlana include honey sherbet, rosewater sherbet, sugar sherbet,lütüf şerbeti, tanrı şerbeti, nardenk şerbeti. Sirkencübin, made from honey and vinegar, was drunk both to quench thirst and medicinally. Another sherbet that was once common was demirhindi (tamarind) but it is rare today. Today the sherbet culture has been replaced by commercial fruit juices, but it still survives today in some Anatolian villages, where sherbets are made from various herbs, including liquorice root.

Ayran

At the mention of traditional Turkish drinks, the first to come to mind is ayran. Its ease of preparation has meant that it is common even in the most remote corners of the country. In the villages it is unthinkable to eat the staple bulgur pilav unaccompanied by ayran, or to fail to serve ayran to a guest. It is almost unimaginable to take a rest in the shade after hard, hot work in the fields and not drink a glass of cold ayran. Even in the cities this is the case, standing and eating a döner sandwich during the lunch break, ayran is practically the only choice. Ayran has practically become a symbol of Turkey, because yogurt has spread from Turkey throughout the world. It is the product of an economy based on animal husbandry. Just like yogurt, ayran has also entered European culture. In addition, sweetened and fruit yogurts are made in Europe. The healthful benefits of yogurt are now well known; ayran is a healthful drink for all the same reasons. It has recently become available packaged in cartons and plastic cups, and is drunk throughout the country.

In certain regions, ayran is churned and is served with a head of foam. For example, a traveler who finds himself in Susurluk near Balıkesir can’t go without having a glass of their famous, rich churned ayran with its characteristic foam. In Anatolia, ayran is traditionally made in a churn called a “yayık.” Today this tradition is disappearing, continued only by certain nomadic groups and in some villages.

Alcoholic Drinks

Rakı

Today raki is Turkey’s national alcoholic beverage. Rakı, or arrack, is an alcoholic beverage drunk south of the Alps, in countries of the Middle East and North Africa – that is to say, in those countries on the periphery of the Mediterranean Sea. It is the latest addition to the mutual components of wine, bread, and olive in the Mediterranean culture.Arrack and its etymological variants, araki, ariki, and raki, which clearly derive from the same root – may be defined as an alcoholic beverage that has been distilled and flavored with anise or mastic. The exact date when the Ottomans made their acquaintance with raki is unknown. A decree issued by Selim II through the kadı of İstanbul in 1573, however makes it clear that this liquor was being consumed at that time in the capital, thus:

“It is my command that on the proclamation of this decree, the Jewish and Christian communities and the gatekeepers of the city of Istanbul shall thereby be admonished and once again cautioned not to allow entrance to open casks and barrels and skins of wine and raki and not to sell to the Muslims what is brought in secretly at night for consumption by the Jews and Christians.”

Wine

In light of the uncompromising ban on wine imposed by Islam – only interpreted by the hypocritical as not applying to other forms of alcohol – how is it that so many Turks have gone on drinking since they were converted to Islam in the 9th and 10th centuries? Practising the utmost discretion, drinkers regarded the spirit rather than the letter of the law. Not only had times changed since Prophet Muhammed addressed his people, but Turks came from an entirely different cultural background. In the 19th century drinking houses were known euphemistically as ‘sherbet houses’, in ironic libel of the ubiquitous sherbet, made of fruit juice, fragrant spices and honey. Read more about Turkish wine and wine routes

Beer

Barley and wheat has been the main staple in the near east regions, however for the most part wheat was in the limelight whereas barley, the raw material of beer, was in the background. However barley was also as old and effective as wheat in the part it played in the development of civilizations. The first place barley was grown and cultivated is, the southwest of the ‘prosperous crescent’ region, in other words, the general region of Syria, Israel and Jordan. 10,000 – 12,000 Years ago, barley traveled to souteast Anatolia, Iran and then continued to China via Afghanistan, Himalayas and Tibet. The archeobotanic findings in the souteast part of Anatolia also backs up this theory.

Hordeum vulgare, in other words barley, was always grown in the the same geography and appeared in the same cultures as wheat, however it was never used in bread making as wheat. Barley was mainly used for making beer, soups, meat stews, tea or feedcrop for sick people and people who are confined to bed. The history of beer goes back before the written times, because of this reason it would be impossible to think of beer independantly of barley. Mesopotamia, and Anatolian civilizations have always produced beer from barley, therefore these near east cultures are considered as the inventors of beer.

Kımız / Kumiss (Mare’s Milk)

A drink of fermented mare’s milk, kımız has a very ancient history among the Turks of Central Asia. Islam was probably responsible for its decline, since horsemeat and mare’s milk were, while not actually forbidden, regarded as undesirable by the Arabs. It survived, however, among the non-Ottoman Turkish peoples of Central Asia.

Kımız was a drink of the privileged, and offering it to guests was a sign of great respect. This is probably due to the difficulty of making it, firstly because mares can only be milked for a short time each year after foaling, and secondly because the proportion of culture to fresh milk, one third, is so high. This posed problems of preserving large quantities of culture from one year to the next, especially since when dried, the culture often became unusable, and had to be kept in liquid form in sealed jars. Only men of rank had the means to do this, and the possession of kımız became a status symbol.

Kımız has been proved to have powerful curative properties, particularly effective for digestive and heart complaints, and most of all for tuberculosis. Before the advent of more modern treatments, many sanatoriums in Russia fed patients with kımız, which was apparently also used in Britain and other European countries. The Scotsman Dr Congrew, who made studies of kımız in the Crimea in 1780, reported on its therapeutic qualities once back in Edinburgh. Further back in history among the Kazakh and Kirghiz Turks, there were physicians specialising in treatment with kımız. To prepare, the culture must first be mixed with an equal quantity of fresh milk and left for 24 hours in a warm place. On the second day, twice the quantity of fresh milk is added, and again left for 3-4 days, for the bacteria to multiply. This is then mixed in the proportion of 1:3 with more fresh milk and poured into leather bags known as saba, which must be frequently shaken up by beating with a wooden stake. In 12-24 hours it is ready to drink.

Kumiss may also be made from camel’s milk. But mare’s milk must be added to the camel’s milk; the kumiss that is produced from such milk is called kımran or kumran. There are various type of kumiss. The Kipchaks recognizes three basic types:

- Savmal kımız – Fresh kumiss: This type is made as described above, and obtained after the second shaking.

- Erek kımız: This is a combination of kara kımız (see below) with savmal kımız, above.

- Kara kımız – “black” kumiss: This strongest variety of kumiss is also known as old kumiss. It is called “black” kumiss not for its color but for its quality, for it is strong enough to cause intoxication. Savmal kumiss is drunk by women, children and the elderly; erek kumiss by the middle aged and less strong men; and ara kumiss by strong young men. Guests are served erek kumiss.

Some Mouthwatering Food Selection from Turkey

Piyaz Salad

Antalya’s piyaz salad is one of the Turkish city’s most famous dishes — and its secret ingredient is its beans. They’re not just any old butter bean, but a small version known as candir, named after the inland province where they’re grown. Delicate and flavorful, candir are mixed, together with tahini thinned with a little water, lemon juice, vinegar, salt, garlic, flat-leaf parsley and olive oil. In the very traditional version, a soft boiled egg is roughly chopped up and mixed through just before serving.

Ezogelin soup

According to legend, this dish was dreamed up by an unhappily married woman named Ezo who was trying to win over her mother-in-law via her stomach. She concocted a zesty soup consisting of red lentils, domato salca (tomato paste — sweet or hot), grated fresh tomatoes and onions, served with dried mint and pul biber (chili flakes) sprinkled on top. There’s no proof it actually worked, but just in case, ezogelin (which literally translates to bride Ezo), originating from a small village near Gaziantep, is still the food of choice for brides-to-be.

Şakşuka (Chak-chuka)

Turkish cuisine incorporates a huge range of vegetable dishes known as zeytinyagli yemegi — foods cooked in olive oil. The majority are vegetable-based and include green beans, artichokes and of course, eggplants. One of the tastiest eggplant offerings is saksuka. Here silky purple skinned cubes of green flesh are cooked with zucchinis, garlic, tomatoes and chilli — how much of the latter depending on where in Turkey it’s made.

Kısır Salad

Kisir is a salad made from fine bulgur wheat, tomatoes, garlic, parsley and mint. There are numerous versions from all over Turkey, but the Antakya one includes nar eksisi (sour pomegranate molasses) and pul biber (hot red chili flakes). They like it hot down south.

Mercimek Köfte (Lentil Balls)

Yaprak sarma

In the Isparta version of yaprak sarma, rice is cooked with tomatoes, a bunch of parsley, onion, garlic, tomato paste, olive oil, black pepper, salt and water. A spoonful of this mixture is placed on a vine leaf, folded in and carefully rolled by hand into neat little cylinders. While leaves are sold at most street markets, the best ones come from a neighbor’s tree, usually picked at midnight. Yaprak sarma are part of Turkish Aegean cuisine and sometimes include a pinch of cinnamon in the mix, a nod to the Rum people, Greeks born in Turkey.

Meatballs of Inegol

Meatballs are so much more than just balls of meat in Turkish cuisine. Each style brings its own unique serve of history. One of the best known is Inegol kofte, invented by one Mustafa Efendi. Originally from Bulgaria, he migrated to Inegol in northwest Turkey in the 19th century. Unlike other Turkish kofte his mix uses only ground beef or lamb and breadcrumbs, seasoned with onions.

Iskender kebab

Located in northwest Turkey, Bursa is famous for three things — silk, the ski fields of Uludag and a type of kebab called Iskender. Apparently a gentleman of the same name first cooked this dish for workers in the city’s Kayhan Bazaar back in 1867. Thin slices of doner meat are reverently laid over pieces of plump pide bread, smothered in freshly made tomato sauce, baptized with a dash of sizzling melted butter and served with a portion of tangy yoghurt, grilled tomato and green peppers.

Çağ Kebap

Hamsili pilav

Hamsi, aka European anchovy, is a staple in Turkish Black Sea kitchen. In the city of Rize, the slender fishes are prepared with rice to make Hamsili Pilav. This dish is cooked in a stock made from fried onions, butter, peanuts, Turkish allspice and raisins, which is mixed with fresh parsley and dill. Then filleted anchovies are arranged over the rice and the whole lot is cooked in the oven.

Perde pilav

The town of Siirt is home to perde pilav, or curtain rice, a rice-based dish wrapped in a lush buttery dough, baked in an oven and served up hot. Usually served at weddings, perde pilav is cooked with chicken, currants, almonds, pine nuts and butter, and seasoned with salt, oregano and pepper. The shape of the dish is thought to represent the creation of a new home — the rice symbolizes fertility and the currants are for future children.

Manti

The most popular type of manti, small squares of dough with various fillings, are those made in Kayseri. This central Anatolian version contains a spoonful of mince sealed into a small parcel, but they use cheese elsewhere. The manti are dropped into boiling water and topped with yoghurt and pul biber (chili flakes). Legend has it, a good Turkish housewife can make them so small that 40 fit onto one spoon.

Testi kebab

Gozleme

Lahmacun

According to Ottoman explorer Evliya Celebi, who roamed far and wide in the 17th century, lahmacun takes its name from the Arabic word lahm-i acinli. It’s a type of pastry made from lahm, meat in Arabic and ajin, paste. The paste consists of low fat mince mixed with tomato paste, garlic and spices smeared on a thin round of pita dough and can be made spicier on request.

Simit

Cig kofte (raw meatballs)

Baklava

Kahramanmaras Ice Cream

Lokum

Lokum, known in English as Turkish Delight, dates back centuries. However, it wasn’t until the mid-19th century that it became a hit with the Ottoman sultans. That’s when corn starch was invented and Istanbul confectioner Haci Bekir added it to the list of ingredients. This simple combination of water, starch and sugar, boiled together to produce delicate cubes flavored with rose water, pistachio and other flavors continues to delight.

Turkey Real Food Adventure

Contact us to prepare you a tailor-made food adventure or choose one of our Turkey packages.